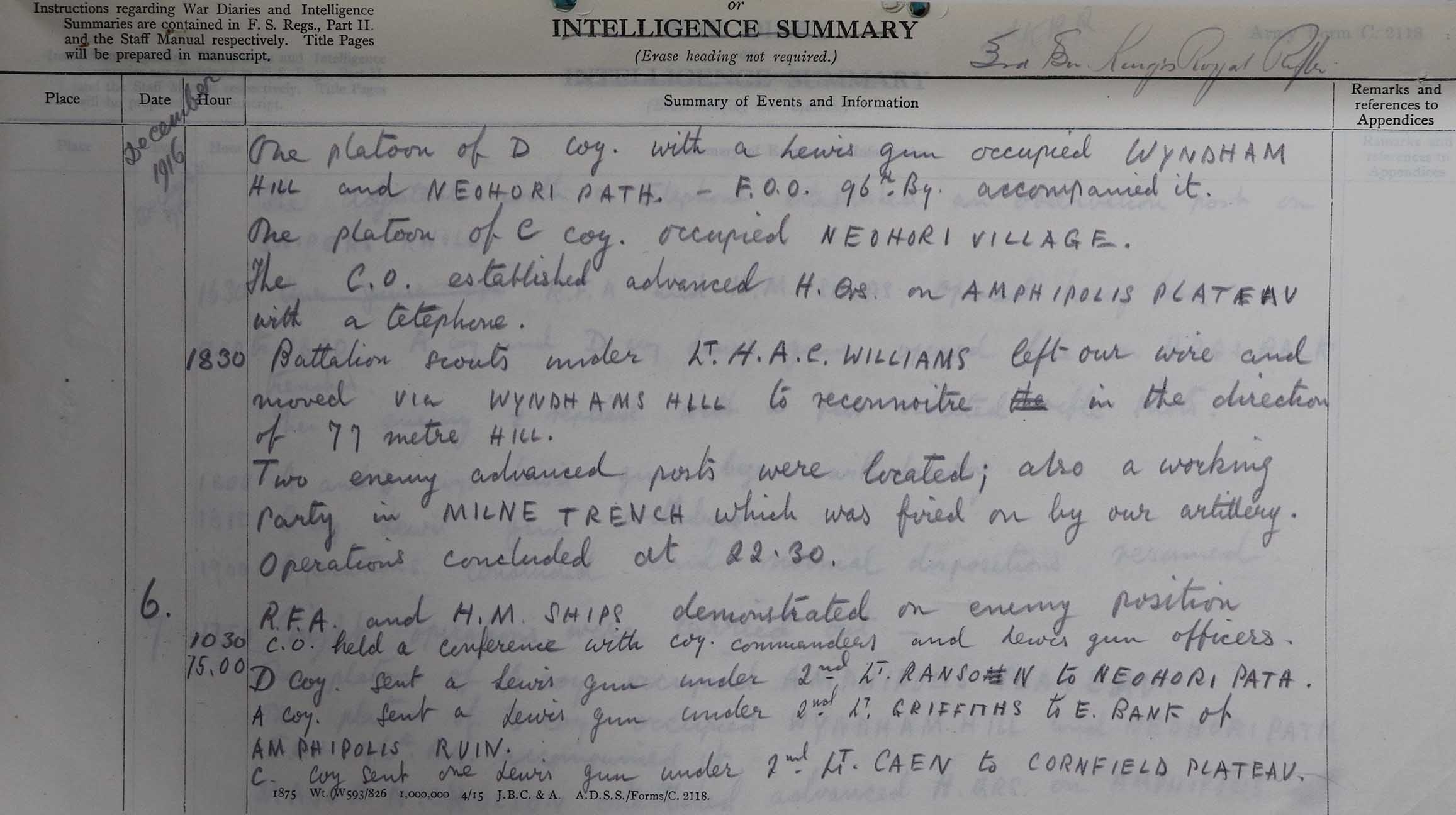

In 2014, during an excavation of the ancient Macedonian tomb near Amphipolis in northern Greece, internet news stories suggested that British troops during the First World War might have disturbed the tomb and moved a large sculpture known as the Amphipolis Lion. The photograph below, which appeared with some of the news articles, does show men of 2 Battalion King’s Shropshire Light Infantry (2 KSLI) near Amphipolis in 1916.

Allied forces in Macedonia during the war did make archaeological finds, some of which are now held by the British Museum and the Louvre, but I wanted to find out if there was any evidence connected to the news stories about Amphipolis. This led me to search through our original records, especially in the army war diaries for the British Salonika Force, to see if there was any mention of the tomb, lion or any other antiquities in Macedonia.

The British Salonika Force (or Army) began arriving in Macedonia in late 1915, joining the Allied Armée d’Orient on the Balkan front. Their war diaries can be found in series WO 95, which was the main source for this research. As British troops began digging defensive positions in Macedonia they uncovered archaeological objects, so an order was issued in December 1915 regarding the collection of antiquities. Around the same time, liaison began with the Greek and French authorities to deal with archaeological matters in general.

Amphipolis and the Struma front

The ancient town of Amphipolis lies just to the east of the River Struma (or Strymon), which formed the eastern part of the Allied front in Macedonia for much of the campaign. I needed more background information about this area, so I used the internet and printed sources such as the Official History of the Great War, to identify where British troops were positioned in Macedonia, and especially to find out which units were located near Amphipolis. I also had to find out about the local topography and landmarks, though changes in place names and even in the landscape made this difficult and complicated the research. The Official History for the campaign in Macedonia provided quite useful sketch maps showing British forces on the Struma front from their arrival in the summer of 1916.

As the map shows, 80 Brigade (part of 27 Division) was based at Neohori (shown at lower right), near the Aegean coast and quite close to Amphipolis. With this information, a more focused search could begin. Even so, there were still some difficulties. For instance, the place name Neohori does not appear to be in use in the area today, and the nearby Lake Tahinos and marshes were later drained. Printed sources also helped to confirm the units based near Amphipolis. The composition of 80 Brigade in mid-1916 was:

2 Battalion King’s Shropshire Light Infantry (2 KSLI)

3 Battalion King’s Royal Rifle Corps (3 KRRC)

4 Battalion King’s Royal Rifle Corps (4 KRRC)

4 Battalion Rifle Brigade (4 RB)

80 Machine Gun Company

80 Trench Mortar Battery

The brigade normally included about 4,200 men, and they remained at Neohori until late 1917, when they were replaced by 82 Brigade (also from 27 Division). Their operations are mentioned to some extent in the Official History, though without referring to Amphipolis itself. During 1918 Greek troops took over along the Struma front, although 27 Division remained in Macedonia until the armistice with Bulgaria and Turkey in the autumn. The area is also shown in a panorama sketch of Neohori.

Amphipolis in the records

Having identified the relevant forces near Amphipolis, I could move on to the records of 27 Division. However, there was still scope for confusion, as it was not always clear how to relate the location of the tomb (now known as Kasta Hill) to the content of the documents. Another problem concerned the dates on which the antiquities were supposed to have been disturbed; while the news stories suggested that this happened during the war, it may have been after the end of hostilities. Various sketch maps of the Neohori position showed the local landmarks and the four battalions there. Though perhaps not very accurate, they could be compared with the satellite image of the area.

Sketch of 80 Brigade positions near Amphipolis, August-September 1916 (catalogue reference WO 95/4887)

The hill named Tafel Kop, in the upper right part of this map, seemed to correspond closely to the position of Kasta Hill and the tomb, and it also gave a clearer view of the 80 Brigade front at Neohori. Among the earliest British troops to arrive at Neohori were the Surrey Yeomanry; in their reconnaissance report of August 1916 (WO 95/4883) they mentioned a ‘tumulus’ near Tafel Kop, which could well be the first reference to the tomb itself. They also found that the enemy had already dug trenches at this position. Apart from this source, neither the tomb nor the lion sculpture were mentioned in any of the records of 27 Division, though there were a few references to a ruin at Amphipolis, possibly associated with the ancient town.

The war diaries of 27 Division also include records covering other troops such as the Royal Engineers and Pioneers, who were responsible for construction works and other manual labour tasks in the Struma area, which sometimes involved digging. 17 Field Company RE, for example, was working at Neohori, but its diary is fairly typical in that it says nothing about antiquities (WO 95/4884).

For the period after the armistice it was quite difficult to identify any useful records, not knowing which British troops might have remained in the area, so that part of the research was inconclusive.

While the results of this part of the search were disappointing, they did strongly suggest that the tomb site was never occupied by British troops, at least in the time before the armistice. Amphipolis itself appears to have been in no-man’s land, being visited by British and enemy troops at various times.