‘The Africans would be in one place and the West Indians would go in their side, and they’d make a big pot of foo foo, the Africans and all dip in. Lucky somebody’s had something today to eat. West Indians would make their dumplings with cornmeal in their house and that would do them for that day, and that is how the poor people had to live around here’.

Oral history interview with Sunday Dennis and Eva Dennis. Tape 2, The Heritage & Cultural Exchange Archive

This quote is from one of the oldest residents of Tiger Bay, an area of Cardiff between the docks and Loudoun Square. Eva Dennis was speaking to The Heritage & Cultural Exchange (HCE), a community-based organisation that aims to chronicle the history and cultural diversity of Tiger Bay and the Cardiff Docklands. Eva lived through the tumultuous period after the First World War and her recollections about some of the earliest forms of welfare are shared among many families of all nationalities.

The National Archives has been exploring the subject of welfare in Cardiff Docks in the early and mid-twentieth century using its own collections, census records and documents and ephemera belonging to HCE and personal collections. Our aim is to understand more about how multi-racial families were supported in interwar Butetown, and to form some historical context to our audio and community project From May to Etta with Love. This project used photographs of multi-racial families taken in Butetown in the early twentieth century as the basis for six audio plays.

Seamen facing starvation

HCE started their work by investigating who was most in need of support and uncovered several reports that documented the plight of merchant seamen who were destitute.

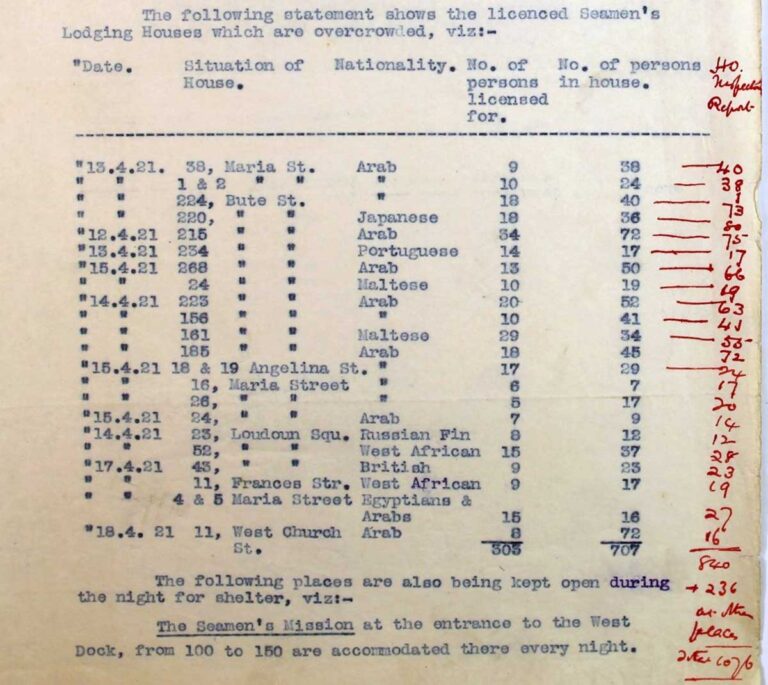

This report sent by the Town Clerk of Cardiff to the Home Office in London highlights the number of seamen from foreign ports who found themselves destitute due to the 1921 Coal Strike.

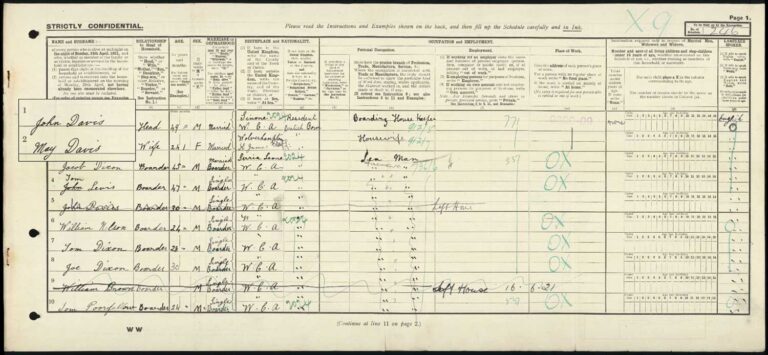

Boarding house masters and the Missions to Seamen were providing shelter without payment but were struggling to keep up with the demand. Number 11 Frances Street was a West African boarding house which was severely overcrowded, with 17 seamen instead of the nine it was licensed to hold. A further two seamen were added to the report and their names can be seen on the 1921 Census.

The boarding house keeper is listed here as John Davies, and the housekeeper is his wife May. John was a seaman from West Africa, and they were married in 1916 and lived together at 11 Frances Street until John’s death in 1923.

All of the seamen listed on this census were from the West Coast of Africa and had no permanent place of residence. Many were Kru (also spelt Kroo) men – an ethnic group originating from Liberia and Ivory Coast – whose origin was recorded as Sierra Leone rather than Liberia to avoid repatriation.

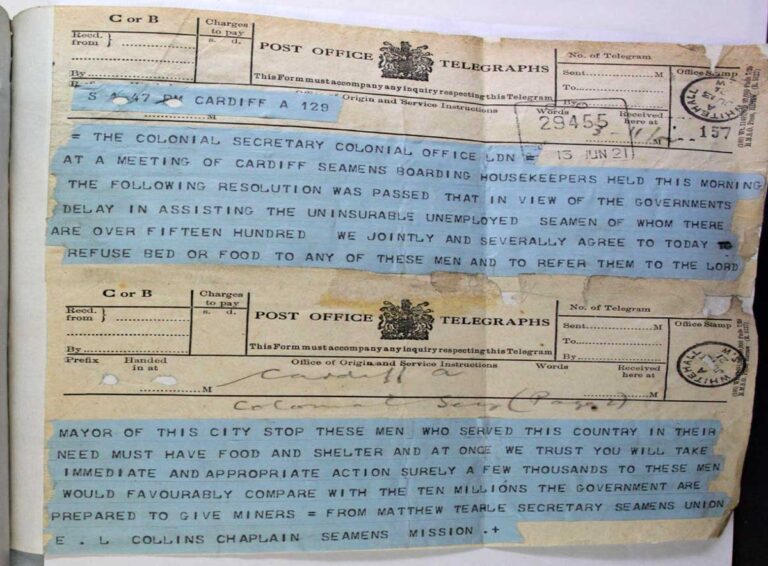

They were seamen risking starvation, and the individuals tasked with supporting them, which included the boarding house keepers, desperately required assistance or all faced being turned out onto the streets. The local workhouse was full and letters to the Colonial Office asking for assistance weren’t having the desired effect.

This telegram sent to the Colonial Office by the Reverend EL Collins, chaplain of the Mission for Seamen, and Matthew Tearle, Secretary of the Seamen’s Union, highlights the plight faced in attempting to support the seamen.

A system of self-help similar to what Eva Dennis referred to was an immediate solution to the problem, but could only provide temporary support, which was unsustainable in the long term.

Help from ‘Fellow Countrymen’

Support came from individuals outside of Butetown who were keen to help.

Letters to the West Africa Magazine alerted authorities in Africa about the plight of Africans in Britain, and limited funds were sent to support seamen with payment of rent.

Organisations such as the Kru Fraternity were set up by West African Kru seamen to ensure the sharing of goods was more evenly distributed, and individuals met within each other’s homes once a month to discuss current affairs and the needs of the community. The group was set up in Cardiff, but other major seafaring ports had their own groups which seamen could join. Liverpool had a National Kroo Society and Manchester had a Kru/Kroo Club. Due to the group’s popularity with people outside of the Kru community (in Cardiff), a new organisation called the Sons of Africa (which shared the name of the 18th-century organisation founded by Olaudah Equiano) was set up to accept a greater number of individuals.

The Sons of Africa began in much the same way as the Kru fraternity but encompassed those from outside the Kru community. They also met in private homes and supported seamen and their families. The group had initiatives such as providing shoes for children, day trips and Christmas parties. Members (both men and women) paid into a fund which provided support for funeral expenses, including flowers, and arranged for the use of two carriages.

Poverty rarely improved during this period and individuals lost their homes trying to support the community. John Davies’ widow May had married another West African man in 1924, Jim Sapoe Mannay, and together they had three children. But her young family lost their home at 11 Frances Street as so few of the lodgers were able to pay the rent due. Records show that May continued to take in lodgers at her new address in 44 Corporation Road. Many were ‘Fellow Countrymen’ of her husband, and remained close with her family until her death in 1971.

Centres of support

Welfare in Butetown wasn’t limited to support for seamen and their families. It was for all peoples, and was often intertwined with faith-based organisations that had buildings that could be used to support the wider community.

One of the most fondly remembered was the Angelina Street Mission, which was set up by Mr James Phillips and later taken over by his daughters, who were fondly known as the Phillips Sisters. The Mission accepted everyone and the Whitsun treat day trip for children was the highlight of the year, with local families getting a ride in a charabanc (an open-top carriage) for their annual outing.

Following the Second World War, the construction of new buildings or restoration of other buildings was also an integral part in the work of welfare organisations.

The opening of a Colonial Centre at 135-137 Bute St from 1943 had a committee of local people who visited sick seamen as well as render voluntary services such as clothes repair (see Catalogue reference: CO 876/65). The George Cross Hostel and Social Club, at 132 Bute Street, and New Missions for Seamen based in Bute Crescent, provided shelter for seamen since 1906 and were much-needed meeting places for activities and support. The New Mission had a reading room and provided hot meals and blankets for the destitute.

A community legacy

Organisations such as the Kru Fraternity, the Sons of Africa, and the Welcome Mission offered support to hundreds of families ‘from the cradle to the grave’. Although the original buildings have been demolished, the legacy of these organisations can be seen today through the existence of the Butetown Community Centre. The Centre is situated in Loudoun Square, the heart of historic Tiger Bay, a place where the community can come together and support each other.

The Butetown Community Centre is also home to the Tiger Bay and the World project, which continues to celebrate the history of the community by running heritage projects. The HCE team welcomes anyone who knows more about these welfare organisations to get involved.

You can read more about the 1919 ‘Race Riots’ in Cardiff and Liverpool on our website, or discover more about the HCE, Glamorgan Archives on theirs. You can also watch a 1960 film about Cardiff’s Tiger Bay on the British Film Institute’s website or explore place-based heritage in Wales on historypoints.org.