It is human nature at this time of year, when seemingly under an unbroken canopy of leaden rain-filled clouds and all about seems so lacklustre, and we are tormented either by storms or the thermometer straddling freezing, to daydream about the delights of spring and then, perhaps, to wish impatiently on lazy long hot summer days and warm balmy nights. Thoughts of winter damps turn naturally to summer hues and a logical leap follows to holidays to far-off and not so far off places with blue skies and warmer climes.

Today we can journey to lands at all points of the compass, by land, sea and air and with relative ease. Time and distance may not have been absolutely conquered but advances in technology and transportation mean arguably that these have been at least tamed – but we still flinch at the idea of a 27-hour ‘long-haul’ flight to Australia.

But our understanding of the world, which is so precise and which we take for granted, is relatively modern. Just 300 years ago our knowledge of the world was so imperfect that great areas of the planet, particularly in the southern hemisphere, were mysteries as yet unsolved. Great voyages of discovery and survey were required to resolve these unknowns and to determine with scientific accuracy a reliable map of our world.

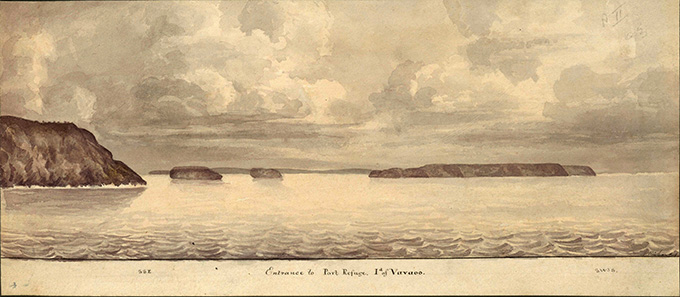

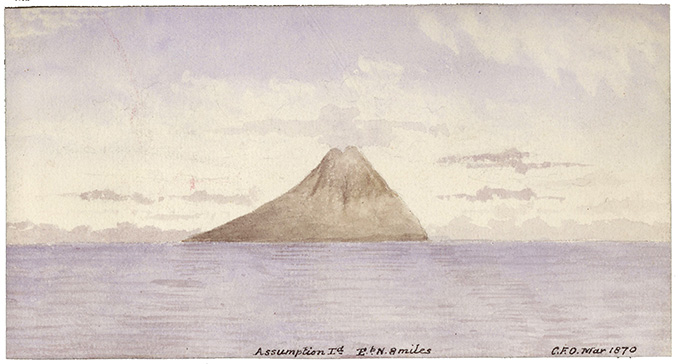

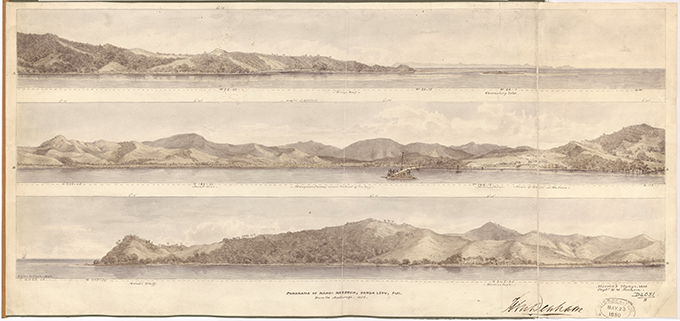

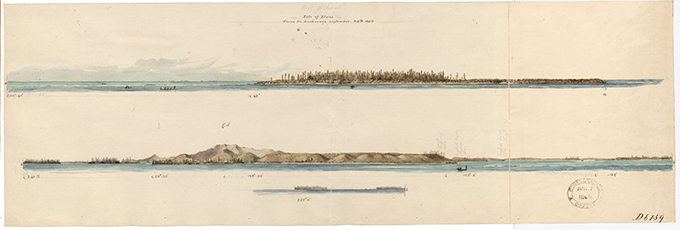

Within the collection held by The National Archives is the ADM 344 series. This series contains the records of the Hydrographic Department of the Admiralty. Discovery, our online catalogue, informs us that ADM 344 ‘contains leaves from albums and sketch books of coastal and riverine views, panoramas and sections which were employed on charts to provide pictorial reference for navigators, especially approaching harbours, ports and hazards, and for the accurate visual identification of geographic locations world-wide.’

A perusal of just a few albums of this series – there are 49 in total and arranged in geographical order – reveals a treasure trove of artwork spanning more than two centuries containing ‘water colour sketches, drawings in pen and ink, engravings, photographs and postcards displaying both survey and military information gathered by naval officers, with contributions also from merchant shipping personnel.’

The albums are relative newcomers to our collection, as the custodial history makes it clear that these records formed part of the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office (UKHO) Historic Archive formerly held at Taunton. They were transferred to The National Archives in 2005, and underwent conservation treatment here, until they were formally accessioned in 2008.

The ADM 344 class is arguably one of the most exciting classes we have as they capture views, often in glorious colour and detail, of a world gone by. The water colour sketches, in particular, are remarkable not least because many were originally executed on board ship. Even to the layperson’s eye the work of individual artists is easily discernible; a striking feature of the artwork is the precision with which the pieces were produced and the skill of the artist where geographical details needed to be drawn with great accuracy. Evident above all is the sensitive use of colour and composition to illustrate weather, features of land, sea and time of day.

Discovery makes it clear that, ‘views of the coast from a seaward position were very important in the early days of exploration and the development of hydrographic survey.’ It’s a personal choice but arguably the artwork concentrating on the Pacific and Southern Hemisphere form the most impressive set of albums. They concern a vast area about which so little was known until relatively modern times. Featured therein are dramatic views of volcanoes, mountainous seas, perilous reefs, coral atolls and much more.

By the time Europeans arrived in the Pacific in the 16th century they were entering a vast region that had been populated by a diverse people who, after successive migrations, had established themselves on their island homes. Spain was the first European nation to enter the region in 1520 and that country laid claim to the entire region via the Treaty of Tordesillas of 1493-4, dividing newly discovered lands between Portugal and Spain.

The Dutch came next and were actively charting the Pacific in the 1640s. This activity included the 1642-3 voyage mapping the western and north-western coasts of ‘New Holland.’ The Dutch were also mapping the northern tip, although they did not realise it, of North Island of New Zealand.

However, between 1763 and 1793, Britain and France experienced a surge of interest in the Pacific. In fact British (English) activity in the Pacific can be traced as far back as Sir Francis Drake’s circumnavigation of the globe – the first time that an English ship sailed Pacific waters. Yet a century would pass before British interest was to be renewed. As such Britain, like France, was relatively late in coming to the region.

British voyages of discovery in the region were made by the Royal Navy. The first came via Admiral Byron in 1764 but was of little success. Others included Dampier’s voyage in 1699, Anson in 1699, Anson again in 1740-4, Byron 1764-5, Wallis and Carteret 1767-8. This was followed by the Botany Bay penal expedition in 1787. France was also active via Bougainville.

However, the most famous explorer was James Cook, who made three epic voyages of discovery in 1768-71, 1772-5 and 1776-9. Cook’s work built upon that of the Dutch. All of this European activity encapsulates a time frame of less than 300 years, but by its end there emerged a more or less complete map of the world.

The ADM 344 class emerged against this backdrop. Discovery reveals that, ‘in 1759, Admiralty Instructions were issued regarding the making of accurate observations, of all useful information about the state of home and foreign coasts, whilst engaged on voyages for whatever purpose. These observations were to include sands, shoals, sea marks, soundings, bays and harbours, times of high water and setting of tides, and in particular directions for sailing into ports (or roads) and for avoiding dangers. They were to include practical information such as the best anchoring and watering places, and descriptions of the best methods of obtaining water, fuel, refreshment and provisions. Fortifications were also to be described and their form, strength and position noted. The instructions specifically mentioned that, where there were artists on board ship who were sufficiently able, they were to provide illustrations (with references and explanations attached) of these details. At the end of the voyage, the illustrations were to be submitted to the Secretary of the Admiralty as part of the official record.’

To anyone suffering the ill-effects of self-diagnosed seasonal adjustment disorder, and in need an instant counter to the drabness of a grey, monotonous British winter, the ADM 344 series provides a welcome boost of vibrancy, colour, beauty, wonder and discovery.