I have been a heritage scientist at The National Archives for four and half years now. During this time I have identified materials, studied the condition of the collection, tested preservation methodologies, and advised on scientific matters. The evidence from these activities has impacted how we look after our collection whether it be how an adhesive is best removed from a paper or how best to clean the collection.

One of the projects that I have found most interesting involved the analysis of a series of wallpaper samples for the book, ‘Bitten by Witch Fever: Wallpaper and Arsenic in the Victorian Home’ by Lucinda Hawksley (Thames & Hudson Ltd, 2016). This book explores the history of the use of arsenic-containing compounds throughout the 19th century home, particularly in wallpapers, and the impact that this had on people’s health.

Wallpapers had become increasingly affordable due to the introduction of new manufacturing techniques and are reported to have often included arsenic compounds during this period, Scheele’s Green for example. Lucinda Hawksley contacted us to see whether we could substantiate these claims with scientific evidence.

The samples

Our collection includes a diverse series of wallpaper samples in its Board of Trade Design Registers. Designs often feature plants and animals in colour palettes ranging from the muted to the colourful and in sizes from the small and delicate through to the large and bold.

Designers and companies submitted these samples to the Board of Trade in order to copyright the designs. They were adhered onto the pages of large volumes with descriptions about when the designs were registered and by whom, recorded in a separate volume.

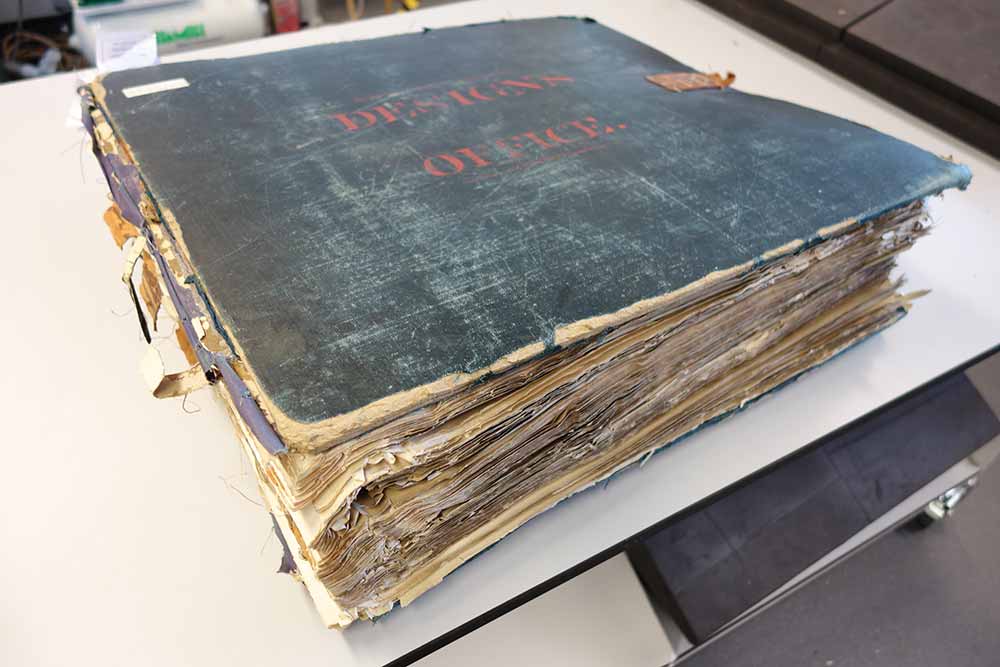

BT 43/103 is a bulky volume that contains over 450 wall hanging designs that were registered between 1879 and 1881

Over 200 samples, registered between 1879 and 1881, had been selected for us to analyse from the volume BT43/103 (Figure 1). The descriptions are available in the accompanying volume BT44/9. Thanks to a cataloguing project supported by volunteers and the Arts and Humanities Research Council, detailed descriptions are now available on Discovery, our catalogue.

XRF analysis

We have our own portable X-ray Fluorescence (p-XRF) analyser. Out of our entire lab, this is my favourite piece of equipment because it can rapidly identify elements (for example, arsenic, iron, lead, tin). It was the perfect choice for indicating whether arsenic was present in the paints used on the wallpaper samples.

- The central design was registered on 13 August 1879 by William Cooke, Leeds (catalogue reference: BT 43/103/338172)

- XRF analysis found it highly likely that the cream petal contains an arsenic-containing pigment

- Detail of XRF analysis showing metallic pigment

Analysis was complicated however due to the poor condition of the volume, its large size and heavy weight. We also needed to analyse the samples without removing them from the volume. By working closely with conservators I developed a method of p-XRF analysis that was safe to use on the wallpaper samples and volume yet gave the results we needed in the short time available. This included developing a supporting structure on which to place the opened volume and placing polyester between the design and the page to which it was adhered.

- Wall hanging design registered on 13 August 1879 by William Cooke, Leeds (catalogue reference: BT 43/103/338242)

- An area of a wheat sheaf containing green/black/yellow pigments was found to be highly likely of containing an arsenic-containing pigment

Results

I took over 430 measurements from various colours within 279 wallpaper samples; over 164 of these samples were likely to contain arsenic. While arsenic is often associated with green shades in wallpapers I found that some green shades did not contain it, while some shades of cream, yellow, and brown did.

Despite arsenic being present in some wallpaper samples, the quantities are very low and with limited exposure, controlled environmental conditions and careful handling, they do not pose a health risk to readers.

Design registered on 14 November 1879 by Jules Desfossé, Paris and London; the yellow/brown circle within a triangle was highly likely to contain arsenic-containing pigments (catalogue reference: BT 43/103/342828)

Working on this project was a great learning experience for me and gave me the opportunity to work with what I feel are some of the most fascinating and beautiful records within our extensive collection. I’ve definitely been bitten by the XRF bug and look forward to the next opportunity use our p-XRF analyser to enhance our understanding of the collection.

- Wall hanging design (right-hand design) registered on 13 August 1879 by William Cooke, Leeds (catalogue reference: BT 43/103/338184)

- XRF analysis of the green and metallic gold border was inconclusive and arsenic was not detected in the yellow with metallic gold background of the design

Detail of the design showing the metallic pigment (catalogue reference: BT 43/103/338184)

A fascinating article and excellent research. The arsenic might not pose a risk to readers but I wonder what the rate of illness amongst the workers was, if they ever became ill and if they had made the connection? Hatters working with lead knew there was a connection but I don’t believe they knew what caused it initially.

Thank you for your comment Faith. Your query is an interesting one and one which Lucinda Hawksley explores particularly well in Chapter 2 of her book. Her research does suggest that wallpaper factory workers suffered greatly from working with, and particularly crushing, arsenic-containing pigments, although a rate of illness is not noted. In 1839, some had warned of the dangers of Scheele’s green which gives off an arsenical gas when damp, but these warnings were initially ignored by wallpapers manufacturers. While I don’t know when Scheele’s green ceased to be used, another arsenic-containing pigment, Schweinfurt green, was still in use almost 50 years later in 1888. For more information please see ‘Bitten by Witch Fever: Wallpaper and Arsenic in the Victorian Home’ by Lucinda Hawksley (Thames & Hudson Ltd, 2016) which is available from the National Archives Bookshop (http://bookshop.nationalarchives.gov.uk/9780500518380/Bitten-By-Witchfever/).

The chapter ‘Poisonous Pigments: Arsenical Green’ in ‘Fashion Victims: The Dangers of Dress Past and Present’ by Alison Matthews David which discusses the use of arsenic in clothing and accessories includes illustrations from the Wellcome Library showing the effects of arsenic on artificial flower makers hands (1859). The chapter opens with a vivid description of the gruesome death of a 19 year old artificial flower maker from ‘accidental’ poisoning in 1861.

What does limited exposure mean in terms of risk to researchers and staff.

Thank you for your question David. The health risks posed to researchers and staff by our arsenic-containing wallpaper samples is very low. This is because, arsenic-containing pigments are a risk when ingested, inhaled, or in contact with the skin. This contact is unlikely to happen when following the National Archives’ handling policy, particularly washing hands after handling collection material, turning pages with care, and not touching the surfaces of designs such as this.

Hi Helen,

Fabulous blog thank you! Have you looked into participating in the Getty-Yale XRF workshop? I only mention it as you say you have been “bitten by the XRF bug”…..I HIGHLY recommend taking it if you have not 🙂

Thank you for your recommendation Kristin. I will look out for information about the next workshop. Past events sound to have been fascinating.

Have you considered that arsenic oxide may have been used in the paste used to stick the wallpaper samples in the book? Paste maker`s eelworm Turbatrix aceti were commonly found in the paste, attracted to it as it went off. I would not be surprised if arsenic was added to the paste to kill these off. These eelworms ate commonly found in furu nori.

Hi Vincent, Thank you for your comment. This is an interesting piece of information that I wasn’t aware of and will keep in mind for future analysis. In this case, the wallpaper samples that I analysed were only pasted in the corners and I was careful to avoid these areas during analysis.

[…] tested positive for arsenic in recent studies. (the process is documented in a fascinating blog post by heritage scientist Dr. Helen Wilson.) How did this fatal substance wind up in wallpaper? In […]

Hello!

I am doing some home restoration on my house built in 1880 and found some hand stamped green wallpaper. How concerned should I be?