Although a work of fiction, Hilary Mantel’s books Wolf Hall and Bring Up The Bodies are steeped in well-researched fact which is supported by documentary evidence at The National Archives and elsewhere. The current dramatisation of the novels in BBC 2’s Wolf Hall prompted me to unearth some of the many related documents we have which echo what we are watching each Wednesday night.

Be aware that this blog post includes plot spoilers, so do not read if you do not already know how the stories of Thomas Cromwell and Anne Boleyn unfold!

In the State Papers – records kept by the Secretaries of State – we have Cromwell’s own archive, forfeited at his attainder in 1540. Most of this represents his in-tray (letters and petitions he received) rather than the correspondence he sent out in the course of the king’s business. Nevertheless, his records and related documents provide tantalising glimpses into the world of the Tudor court which is currently being brought so compellingly to life on our television screens.

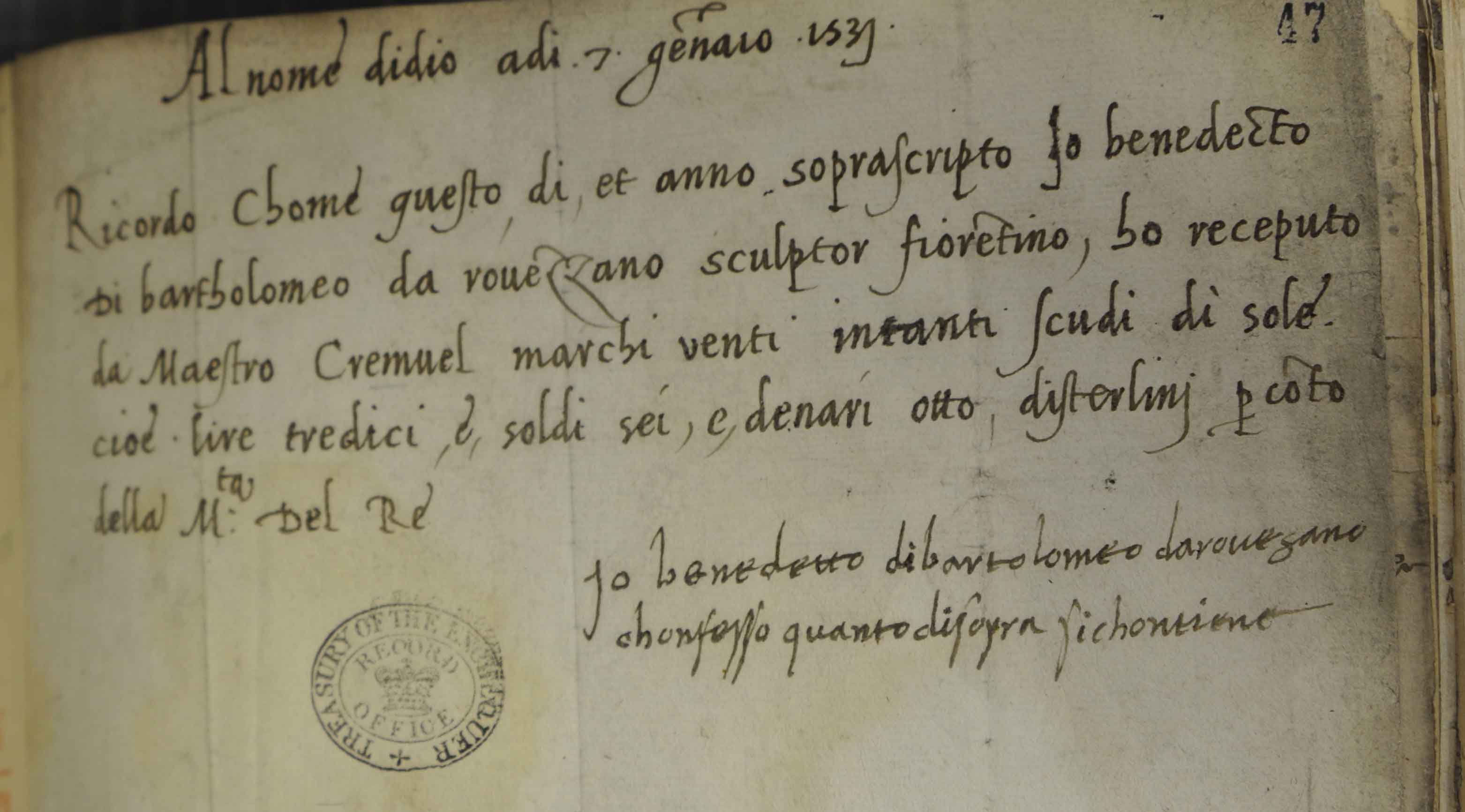

In episode 1 (Three Card Trick) of the BBC’s Wolf Hall, we saw Anne Boleyn playing with Cromwell’s name, pronouncing it as ‘Cremuel’, with a French accent. We can actually find examples of this exact spelling by French and Italian correspondents in the State Papers. The Spanish ambassador, Eustace Chapuys, is known to have spelled Cromwell’s name thus in correspondence to the Emperor Charles V and an Italian sculptor recorded this spelling in his receipt for a payment made to him on the King’s account by Cromwell (SP 1/65, f.47).

Cromwell referred to as ‘Cremuel’ in this receipt for payment to the Florentine sculptor Benedict di Bartolemo da Rovezzano (SP 1/65, f.47).

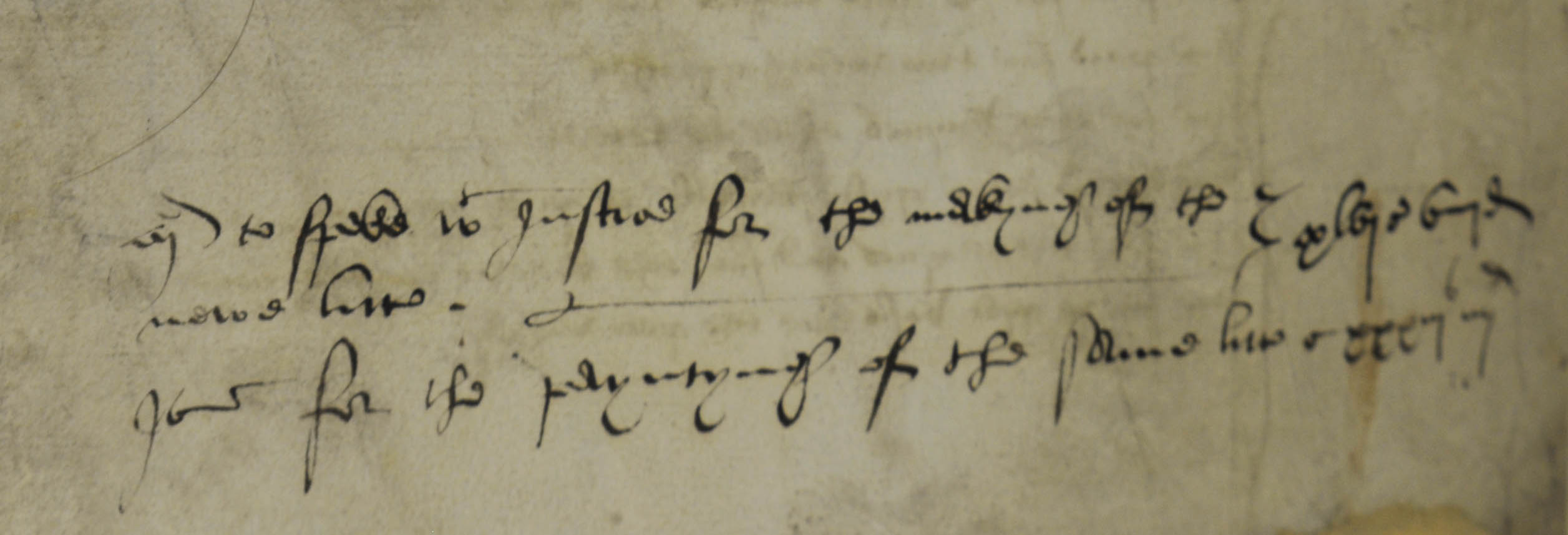

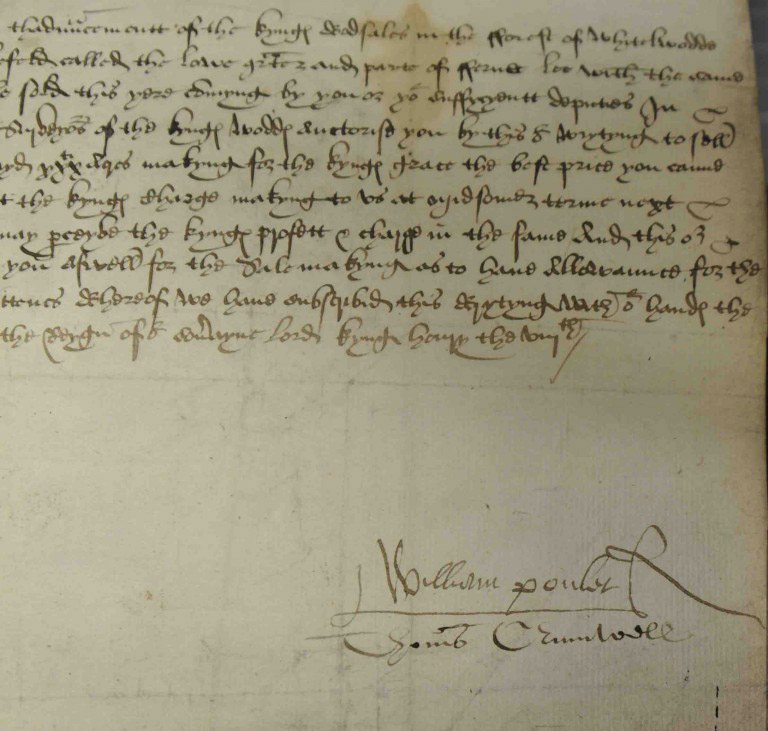

Of course, this was a period when spelling was highly fluid, and names could be rendered in several ways even in the course of a single document. Cromwell was also frequently addressed as Thomas Crumwell and often signed his name with that spelling as can be seen from this extract (SP 1/81, f.32).

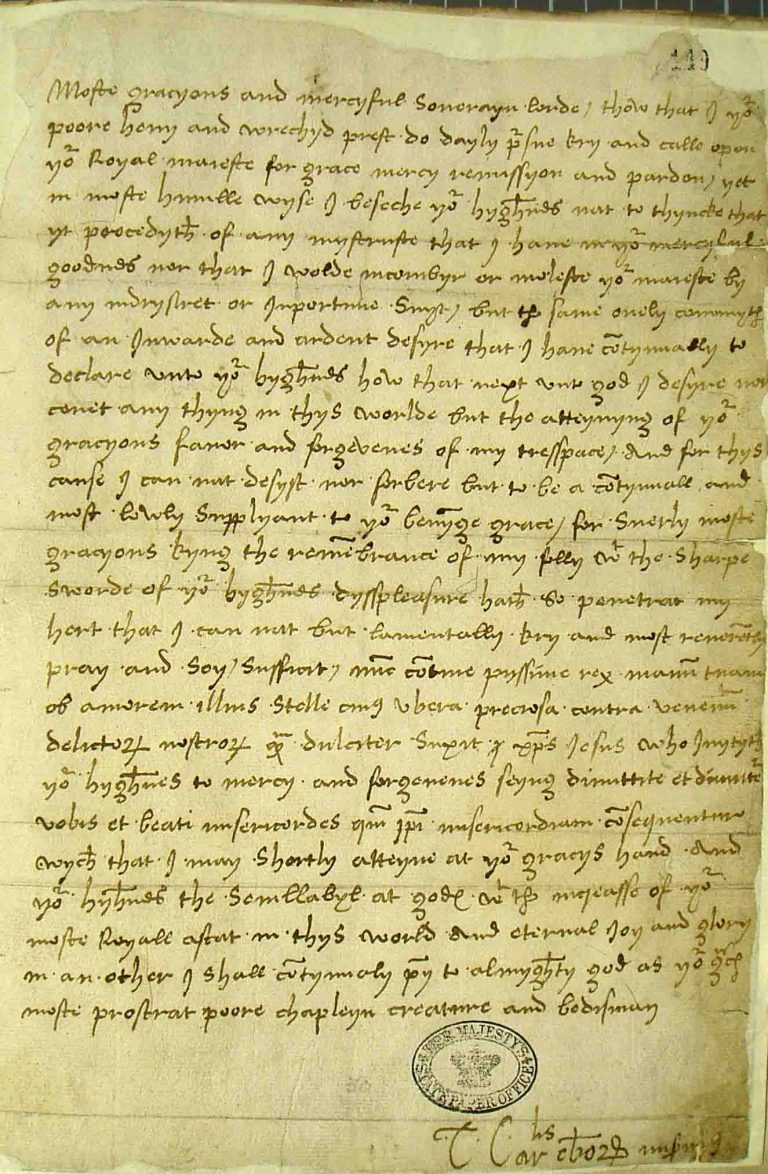

In episode 2 (Entirely Beloved), Cardinal Wolsey’s fall from power culminated with his death on his journey back to London under arrest in 1530. A poignant and very humble letter from Wolsey to Henry VIII records his desperate attempt to regain the King’s favour. He notes that ‘I, your poore, hevy, and wrechyd Prest, do dayly pursue, kry, and calle opon Your Royal Majeste for grace, mercy, remissyon, and pardon’. He goes on to assure the King that ‘next unto God, I desyre nor covet any thyng in thys worlde, but the atteynyng of your gracyous faver, and forgevenes of my trespace’…‘the remembrance of my folly, with the sharpe sworde of Your Hyghnes dysspleasure, hath so penetrat my hert…’ (SP 1/55, f.149). His pleas failed to invoke the King’s mercy, however, and he died in disgrace.

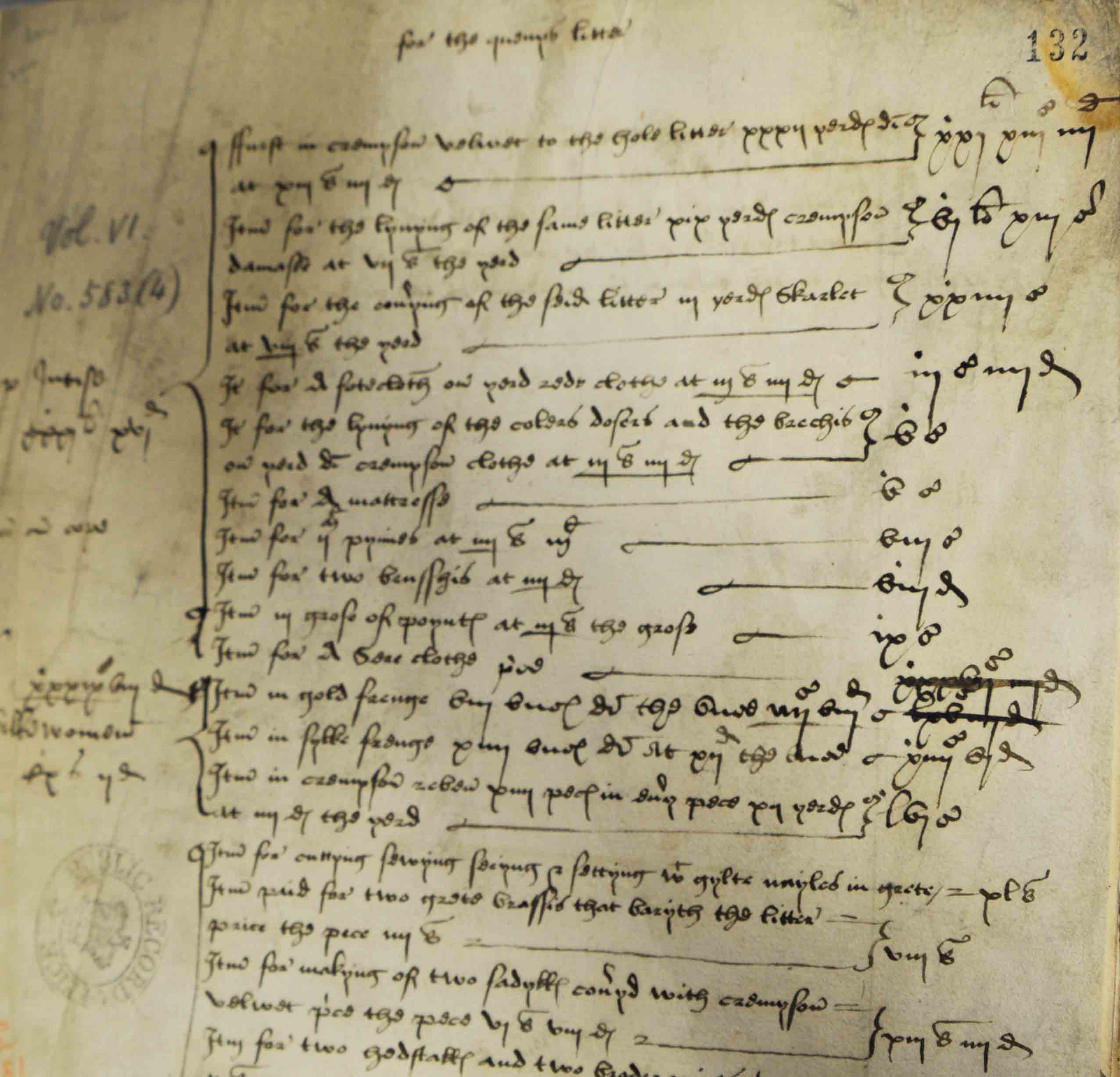

In episode 3 (Anna Regina), we saw Anne Boleyn in her triumph, at her coronation. This document (SP 1/76, f.132) gives a hint of the extensive planning and organising which went into staging such an event, in this instance listing just those materials needed to decorate the Queen’s litter and horses which carried it to her coronation. Items include 32 yards of crimson velvet, a mattress, 10,000 gilt nails, 2 great double collars stuffed with bells, 10 gilt roses and 10 pommels with roses.

Below the list of items, on the second page in different handwriting, is written ‘Mem. To speak with Justice, for the making of the new litter, 46s. 8d.; for the painting of it, 33s. 4d.’. The handwriting resembles that of Cromwell himself. If it is indeed in his hand, it demonstrates how Cromwell immersed himself in the detail of the King’s business.

A note on the list for the preparations for Anne Boleyn’s coronation, possibly in Cromwell’s hand (SP 1/76, f.132).

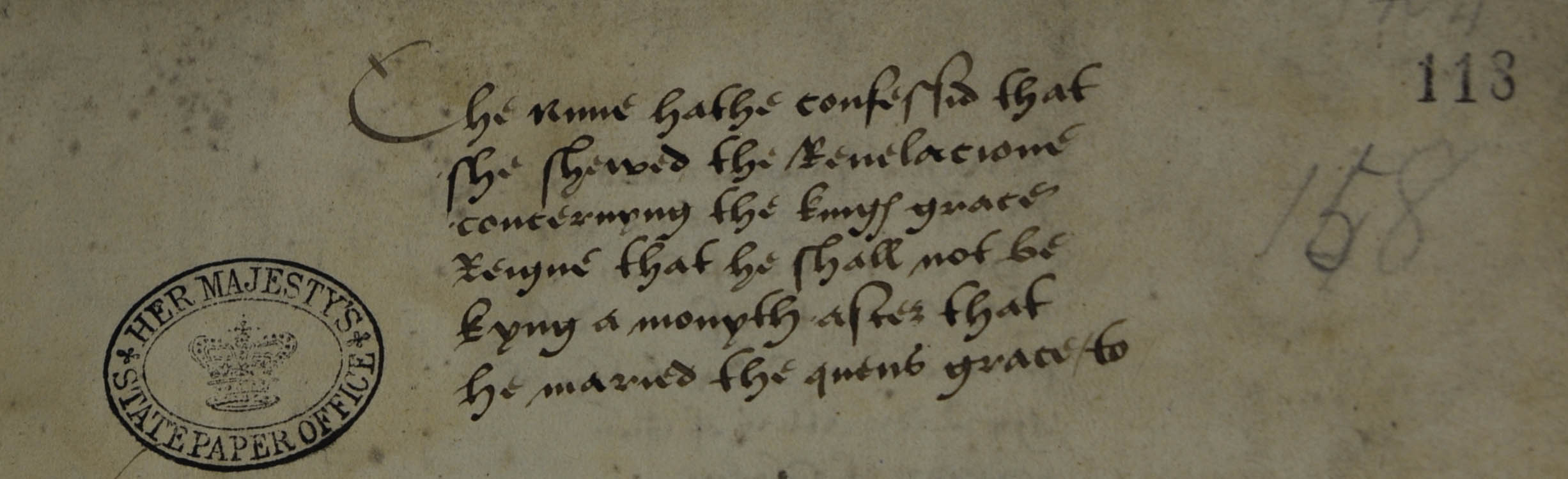

In the forthcoming episode 4 (The Devil’s Spit), the ‘Nun of Kent’, Elizabeth Barton, is due to make an appearance, foretelling the King’s death because of his new marriage – a treasonable offence. Records summarising the case against her and listing those high-status individuals who had been in contact with her can be found in the State Papers. In this document (SP 1/80, f.118), one of the charges against Barton is spelled out. ‘The Nune hathe confessed that she shewed the Revelacione concernyng the Kinges grace reigne that he shall not be kyng a monyth after that he maried the quens grace, to Doctor Bocking, her gostly father’ and others.

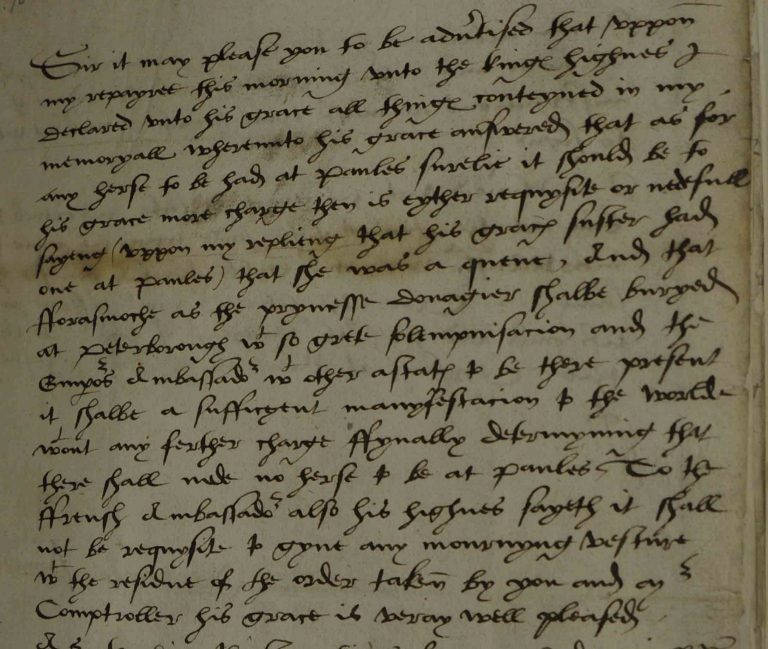

We can expect that episode 5 will cover the death of Katherine of Aragon and the response to this of the Tudor court. In Bring Up The Bodies, Mantel has the character ‘Call-Me-Risley’ (otherwise known as Thomas Wriothesley) tell Cromwell that the King rejects the idea of burying Katherine at St Paul’s Cathedral in London, with full royal pomp and court mourning, despite the fact that Henry’s sister, the Dowager Queen of France, had been buried there. Our documents show that the King’s conversation was with Ralph Sadler instead, and he dutifully reported this to Cromwell, but the essence of Henry VIII’s response was the same (SP 1/101, f.50) – ‘…his grace answered that as for any herse to be had at Paules surelie it should be to his grace more charge then is eyther requysite or nedefull sayeng (uppon my replieng that his graces suster had one at Paules) that she was a quene, And that Forasmoche as the pryncesse Douagier shalbe buryed at Peterborough w[ith] so grete solempnisacion and the Emp[er]o[ur]s Ambassado[ur] w[ith] other astat[es] to be there present it shalbe a sufficyent manyfestacion to the worlde’.

A report of the king’s conversation with Ralph Sadler about the burial of Katherine of Aragon (SP 1/101, f.50)

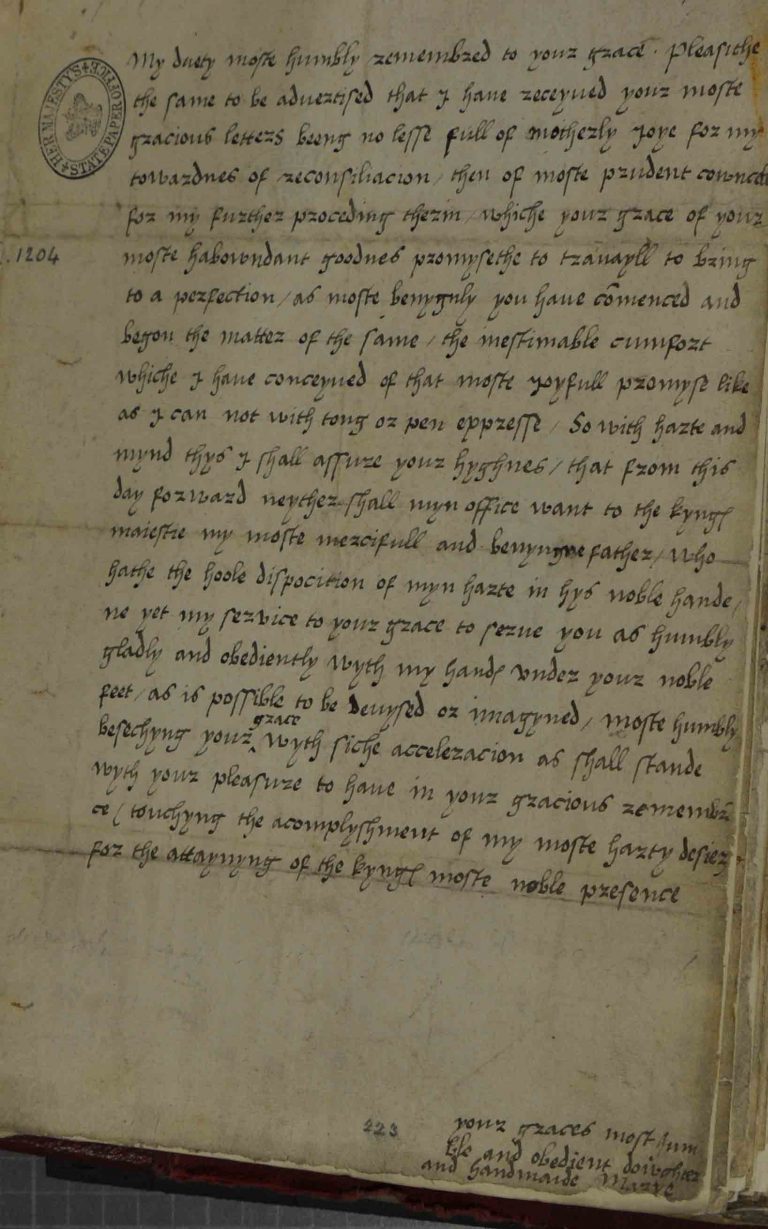

The Wolf Hall television series will culminate with episode 6, which will see the execution of Anne Boleyn and her place taken by the new queen, Jane Seymour. This letter (SP 1/104, f.204) from Princess Mary to her new stepmother demonstrates the dramatic difference between her relationships with Henry VIII’s second and third wives. Previously intensely hostile to Anne Boleyn, Mary tenderly welcomes Jane, pledging ‘to serve you as humbly gladly and obediently wyth my handes under your noble feet as is possible to be devysed or imagyned’.

What I find so compelling about Hilary Mantel’s books, and the plays and TV series which have been derived from them, is her attention to detail, clearly based on thorough research into calendars and contemporary texts. A lesser writer might ensure that major events are historically accurate, but invent the small details. It seems to me that Mantel bases her novels on solid historical evidence, not only of the great political happenings but also of the day-to-day minutiae. Instead, she allows her imagination full rein in areas about which we will never know the absolute truth from documents alone, such as the complexity of relationships between individuals and their intimate conversations – matters as evanescent as the flickering Tudor candlelight.

Why do you say Eustace Chapuys was the Spanish Ambassador? I thought he was the ambassador of Charles V, Holy Roma Emperor.

Hi Sid,

Thanks for your comment. I’m posting this response on behalf of Ruth, the author of the blog post:

Charles V was elected Holy Roman Emperor from 1519 but he was also King Charles I of Spain (Aragon, Leon, and Castile) after March 1516 as a joint monarch with his mother, Joanna. By 1519 he assumed personal rule over the Spanish kingdoms.

Since Eustace Chapuys was from Savoy he was probably more obviously associated with the Hapsburg lands in Burgundy and the Low Countries that Charles V had inherited from his father Philip I in 1506. Once Chapuys was appointed as Charles V’s ambassador to England after 1529 he represented all of the Emperor’s territories. Charles was known by this senior imperial title in England but most of his interest there between 1525 and 1533 were related to the treatment of his aunt, Queen Catherine of Aragon. So perhaps Chapuys’s identification as the ‘Spanish ambassador’ was most appropriate during the period of Henry VIII’s attempt to annul his first marriage.

Best wishes,

Alexa