I don’t read a lot of fiction. I don’t need to, because some of the real stories I have come across in documents held in The National Archives are just as exciting and dramatic as any novel.

HO 45/7900 Registration of births, etc: Fraudulent abstraction of a leaf from the registers for St Pancras Parish: baptism of Elizabeth Laura Keeling

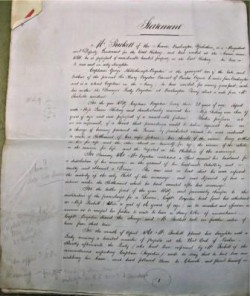

A catalogue search for ‘fraud’ turned up an item of Home Office correspondence entitled ‘Registration of births, etc: Fraudulent abstraction of a leaf from the registers for St Pancras Parish: baptism of Elizabeth Laura Keeling’ dated 1866-1867 HO 45/7900. I thought there must be an interesting story behind this incident, so I ordered the file, which turned out to be a long letter of complaint to the Home Secretary from Mr Prickett of Bridlington. He gave a lengthy account of how Captain George Boynton had come to marry Mr Prickett’s daughter, Elizabeth Ann, very much against her parents’ wishes.

George Hebblethwaite Lutton Boynton was one of the youngest of the 13 children of Sir Henry, the 9th Baronet Boynton, and his wife Mary. This was a wealthy family, but since George had three older brothers he was not going to inherit the title, the money or the family home, Burton Agnes Hall. He must have decided at an early age that his best chance of making money would be to marry it. This is exactly what he did, having found himself a young heiress, Elizabeth Laura Keeling. Her father died in 1832 when she was a baby, leaving his substantial fortune to her, his only child. Not only that, he left it to her outright; under the law at that time a married woman had no separate legal existence from her husband, so that if she Elizabeth Laura married, all of her property would now belong to her husband. She was only 17 when she and George were married by licence at St George Hanover Square.

The wording of the licence was interesting, stating that she had no father living, and no mother ‘living and unmarried’ who could give her permission to marry – unlike a married woman, a widow was regarded by the law as an independent legal being. While this was strictly true, her mother had re-married so her stepfather, Captain Trophimus Hodges, was now her legal guardian, entitled to give or withhold permission. George conveniently failed to mention this, so the licence was issued and the wedding took place.

Captain and Mrs Hodges must have found out just too late in the day to prevent the wedding, and set out in hot pursuit of the couple who were now en route to the barracks at Windsor where George, a captain in the army at that time, was stationed. According to newspaper reports, negotiations took place at an inn, and George agreed to accept a life interest in his wife’s money, with no access to the capital. In return, Elizabeth Laura’s family agreed not to challenge the validity of the licence in court, which would very likely have resulted in the marriage being declared void.

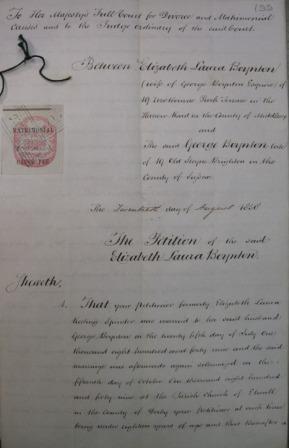

Two years later they had a son, George Henry Keeling Boynton, but the marriage was not a success, and the couple were frequently seen quarrelling in public. When the Divorce Act came into force in 1858, Elizabeth Laura was one of the first in the queue of aggrieved wives filing for divorce, on the grounds of George’s adultery and cruelty towards her. Not only did she win her case, she also recovered all of her money, so Captain George was left without his main source of income.

But even before the decree absolute was granted he had found another 17- year-old heiress, Elizabeth Ann Prickett; George was by now 32. Although both her parents were alive, she seems to have had some independent source of income, perhaps a legacy from another relative. Mr Prickett was not at all happy that his young daughter was receiving the attentions of a soon-to-be-divorced man 15 years her senior. He sent her away to school in London, but George followed her there, so she was brought back to Yorkshire. Mr Prickett was successful in keeping the pair apart for the next three years, but in January 1864 Elizabeth Ann was 21, and could marry without permission.

J 77/2/B27 Divorce Court File: B27. Appellant: Elizabeth Laura Boynton. Respondent: George Boynton. Type: Wife's petition for divorce

In the intervening years she had converted to Roman Catholicism, which meant that she could not marry a divorced man. But if Mr Prickett thought this would prevent her marrying Captain Boynton, he was wrong. She explained that she could marry him if his first marriage was invalid, because he would then be a bachelor in the eyes of her church. If, for example, his first wife was not a Christian then the Catholic church would not recognise the marriage. As it happened, she said, Elizabeth Keeling was Jewish, and had not had a Christian baptism, so the marriage did not count! This was complete nonsense, but there is no way of knowing whether Elizabeth Prickett actually believed it.

But in order to marry in a Roman Catholic church, George had to remove all evidence of his first wife’s baptism, which he achieved by simply tearing the relevant page out of the St Pancras church baptism register. Not only that, he also removed the corresponding page from the bishop’s transcripts at the Bishop of London’s registry. He was always just one step ahead of Mr Prickett, who had been resourceful enough to contact the former Mrs Boynton through the solicitors who had acted for her in the divorce, extensively reported in the newspapers. She even supplied him with certified copy of her baptism entry, which she had obtained shortly before the page was removed, but to no avail.

So despite his best efforts, the marriage took place on 1 October 1865 at the Roman Catholic chapel in Spanish Place, Manchester Square. Mr Prickett’s detailed account of events runs to more than 5,000 words, and you can read the full transcription in the Your Archives pages now held in the UK Government Web Archive. The St Pancras baptism register does indeed have a page missing; page 25 is followed by page 28 in June 1832, and the register contains a note describing the events on the day when it went missing, including a transcript of Elizabeth Laura Keeling’s baptism on 16 June. Unfortunately the other 15 baptism entries from pages 26 and 27 are probably lost forever. The register is held at the London Metropolitan Archives. The Boynton divorce file J 77/2/B27 is here at The National Archives. Both are also online at Ancestry.co.uk.

Captain George’s second wife died in 1877, and the couple had a daughter, Eva, who died unmarried in 1934. George died in 1888, and the first Mrs Boynton died in Paris in 1902, having moved there after the divorce. She never re-married.

We have a number of other records relating to the Boynton, Keeling and Prickett families including wills, court records and army service records. Captain George Boynton’s two marriages and his divorce are by no means the only scandalous incidents in the stories of these families; several of them concern George Henry Keeling Boynton, who turned out to be an even more colourful character than his father. But that’s another story…

Fascinating story, thanks for sharing.

Thank u for the story it help a lot with the family tree my grandpa was Cecil Boynton Thornton his mum was Elizabeth Boynton stocker no father on the birth certificate her mum was also Elizabeth Boynton we think George kneeling Boynton was the father