We usually feel we know where places are, or we have a good idea where they are; if we don’t, we can look them up. Ultimately we can point to them on a map. We might even talk about ‘pin-pointing’ them.

I feel comfortable with the idea of pointing to London on a map. I should do; I live there. But what, exactly, am I pointing at? My finger might come to rest on an area that roughly covers the middle of the city. That seems perfectly acceptable. But is that London? It will probably be more like ‘Inner London’ or maybe what’s referred to as the ‘City of London’. What about ‘Outer London’? Or even ‘Greater London’? Aren’t all of these areas relevant? As entities they are each officially recognised in the Index of Place Names in Great Britain (IPN) published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). So if the ONS can count them, then surely they must count!

On the other hand, if I search for ‘London’ in Google Maps I am presented with a default view that stretches from Potters Bar in the north to Sutton in the south and from Slough in the west to Romford in the east. Is all of that London? According to the ONS, Potters Bar is in the county of Hertfordshire, Sutton is in Surrey, Slough is in Buckinghamshire and Romford is in Essex.

The Google Maps view does also ‘pin-point’ London: a helpful red marker hovers over a very precise spot with a grid reference of 51.528308,-0.3817765. If you scroll in you discover that ‘London’ can be found just next to the statue of Charles I at the Trafalgar Square end of Whitehall!

So the more you consider the notion that it is easy to name a place or locate it, the less accurate that assumption appears to become. I have just questioned the inclination to pin absolute truths to the position and extent of places, while at the same time I am plainly swayed by my own feelings about where I believe places are or should be.

I’ve heard London referred to as a series of villages and there can be numerous reasons why you might claim attachment to one or another of these. Subconsciously, it might be the result of the local station that you regularly commute in and out of. Deliberately, it might be an attempt to bag perceived socio-economic status (a tactic beloved of estate agents). It could just vary from context to context: from easing communication with an outsider (’rounding up’ to somewhere they might have heard of) to conveying affiliation with a local (’rounding down’ to the same shared neighbourhood).

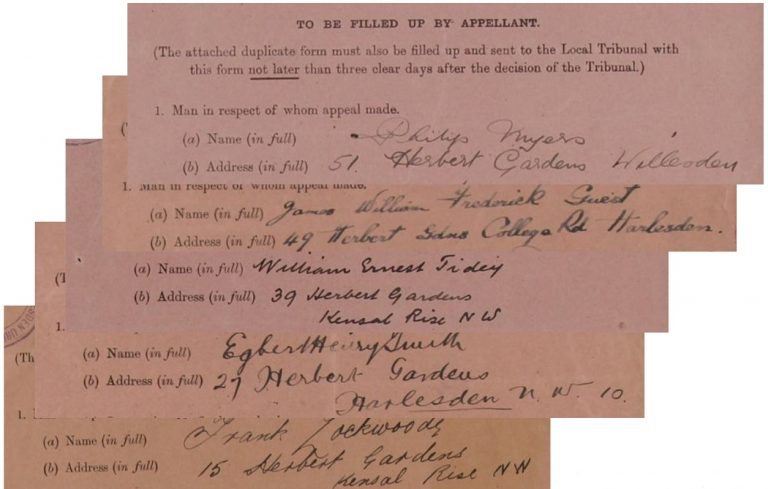

The archives show us that inconsistency in personal place name attachment is nothing new: I have found a stark example in our series MH 47, the Middlesex records of appeals against military conscription in the First World War which, significantly, were filled out by the petitioners themselves (not by officials). Three areas are listed here in just five petitions from the same side of one street (Herbert Gardens).

Handwritten extracts from the five sets of appeals (catalogue reference: MH 47)

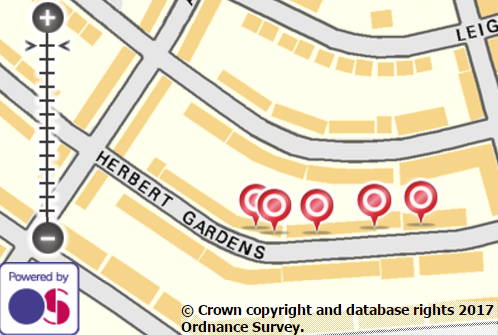

Locations of the five appellants’ houses shown on a modern Ordnance Survey map

We could explain this by locating Herbert Gardens roughly half way between Harlesden and Kensal Rise (and both within the Parish of Willesden).

For the researcher though, such variation raises questions about any search that includes location, not least when it comes to finding records by place name only. A technically-savvy historian might suggest the use of geospatially sophisticated distance or boundary-based querying. However, less than 1% of our record metadata includes the technical geo-referencing that would enable that – even if we do overlook the debate I raised earlier with regard to the true ‘exactness’ of either a coordinate or a wider boundary.

And personal interpretation is only one of many obstacles encountered by researchers trying to identify places through time: Which place exactly? What does the original record say? What does its descriptive metadata now say?

Name variation happens today (for example Newcastle, Newcastle on Tyne and Newcastle-upon-Tyne) but the further back you go the more of it you have to contend with. Some of it may be plain old misspelling (compare Newcastel Tyne in this Second World War record or Newcastele-upon-Tyne in one from 1910). But once you’re into earlier centuries, anything goes: Newcastle upon Tine (1810), New Castle upon Tyne (1687), Newcastell (1591), New-castle-on-Tyne (c.1500).

Even in the same kinds of record, place names can be hard to pin down. In the 1841 Census there was an Ozendike that ten years later was recorded as Oxendike. By 1861 it was Ossendike which finally settled into Ossendyke from 1871 onwards.

Sometimes places simply do just change their name. With the passage of time the change might be organic as places grow and merge or are subsumed by a neighbour (and a new name). The 1841 Census has an entry for Beard, Ollersett, Thornsett and Whittle hamlets collectively known as Newmills. Today, only Thornsett and New Mills still exist on the map; Beard and Ollersett can only be found as vestiges in street names; and “Whittle” appears to have disappeared.

Names can also find themselves subject to natural linguistic evolution (Pleymondestowe mutating to Plemonstall and then Plemstall for example). For periods such change can even result in several alternative forms being used simultaneously. I see that a Census enumerator in Berkshire in 1861 was careful to note Brightwaltham (also known as Brightwalton or Brickleton).

There may be an administrative, revolutionary or politically motivated reason behind a change of name. Take for example the historically anglicised Carnarvon now officially known by its proper Welsh spelling of Caernarfon. Even taste can come into it. In 1841 I found a Shitlington in Bedfordshire and, disturbingly, a Nether Shitlington in Yorkshire – whereas today you’d need to look for the disinfected Shillington and Sitlington respectively!

Places on borders might have bilingual forms. Borders themselves are fluid and move to and fro with regularity. Up until 1841 the parish of Ibstone turns up in the archives under both Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire. It’s been exclusively on the Buckinghamshire side since then, but beware: it also used to be known as Ipstone. And Ipston.

Put some or all of this together and you could be forgiven for feeling quite lost. If I were writing this in July 1501 I might place myself right now in Cayho, in the parish of Westshene. But since it’s April 2017 I’ll say this is Kew, in the Borough of Richmond, in Surrey. Under different circumstances I might equally refer to this suburb as Kew Gardens, in London. Would you know where I meant?!

Many of the questions above have arisen during work for the Traces Through Time project.

I would say that the spellings of Newcastle-on-Tyne is not just due to different names but transcription errors at TNA, for example the various spellings of London (as Lodnon) and for Guildford the middle ‘d’ was not listed by the departments!. London has been governed by various administrative movements (London Government Acts , particularly the Local Government Acts of 1963 and 1974). Some streets in London were half in one borough and half in another. You do have think about places like Newcastle (Northern Ireland, Newcastle-on-Tyne and Newcastle-under-Lyme) and Bradford (Yorkshire and in Avon). London was deemed to be the City of London before the reorganisations, being surrounded by Middlesex, Surrey, Essex and Kent.

Intrigued to see another Hillyard working in archives….

Hello from the Mining Institute in Newcastle – upon Tyne as mentioned in the post!

J

Fascinating blog! 🙂

A brilliant exposition, well thought out

Another interesting example is Whittlesey in Cambridge. Now the town is almost always known by that spelling, but early on the railways settled on the then current variation of Whittlesea, and the station still uses that version.

Of course Richmond is now only in Surrey in postal terms – the Richmond-upon-Thames is a London Borough (straddling ancient Surrey and Middlesex). And counties have not been mandatory in postal addresses for over 20 years (despite what some websites would have you believe when they ask you for your address) and are close to being dropped altogether https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Postal_counties_of_the_United_Kingdom

Correction: According to the ONS Romford is in London, not Essex.

Thanks for the correction. The ONS does list Essex as the historic (pre 1974) county for Romford but you are quite right: London is the ONS region for statistical purposes and Greater London is its lieutenancy county.