Detail from National Savings poster (catalogue ref: NSC 5/350. 1952)

Inspired by the likes of the Great British Bake Off, I have for some time wanted to look in to recipes within The National Archives and what they can tell us, and so took the opportunity for my blog post this week.

The wonderful thing about taking a topic such as ‘recipes’ or ‘food’ as a theme in archival research, is that it cuts across many series, subjects and people.

As Felipe Fernandez-Armesto suggests in the preface to his book ‘Near a thousand tables: A history of food’:[ref] 1. Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, Near a thousand tables: A history of food, 2002, New York: Free Press, p. ix[/ref]

‘The great press baron Lord Northcliffe used to tell his journalists that four subjects could be relied on for abiding public interest: crime, love, money and food. Only the last of these is fundamental and universal … Food, moreover, has a good claim to be considered the world’s most important subject. It is what matters most to most people for most of the time.’

As social historians will contend, you can arguably gain an insight in to the lives of history’s most ‘silent’ or ‘hidden’ members through knowledge of something as simple as what they ate – its amount, its availability, its source and its variation all indicate much more about the everyday lives of those who ate it. It’s such a day-to-day activity, yet it is recorded in many different ways within official records.

As with any subject such as this, the more you look, the more you find, so there is a lot of work to be done. But I thought I’d share some of my first interesting finds on the blog today and return with more (and perhaps a trial or two!) at a later date…

The concern surrounding the nutrition of the poor during the 19th century is a huge research topic in its own right. Our records of correspondence in MH 12 regarding workhouses for example, contain numerous discussions of the concerns, adjustments, variations and costs involved in the diet of the inmates.

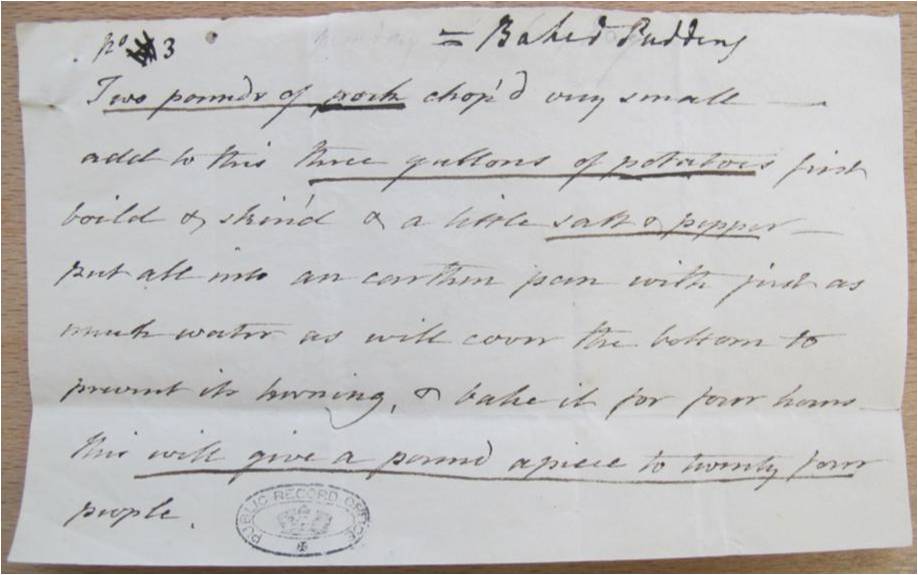

A record from earlier in the 19th century along the same theme can be found in the papers of Charles Abbot, 1st Baron Colchester, in PRO 30/9. Entitled ‘Miscellaneous recipes for soups, puddings, etc. for feeding the poor in time of scarcity’, the file contains a selection of recipes with variations on the theme of potatoes, pork and mutton in quantities large enough to feed at least 24 people at a time, at the lowest possible cost.

Recipe from ‘Miscellaneous recipes for soups, puddings, etc. for feeding the poor in time of scarcity.’ 1811. (catalogue ref: PRO 30/9/10/21)

Leaping forward into the 20th century, evidence can be found throughout the records of government concerns surrounding feeding and ensuring the nutrition of the nation. As you would expect, this is particularly apparent during the rationing period during and after the Second World War.

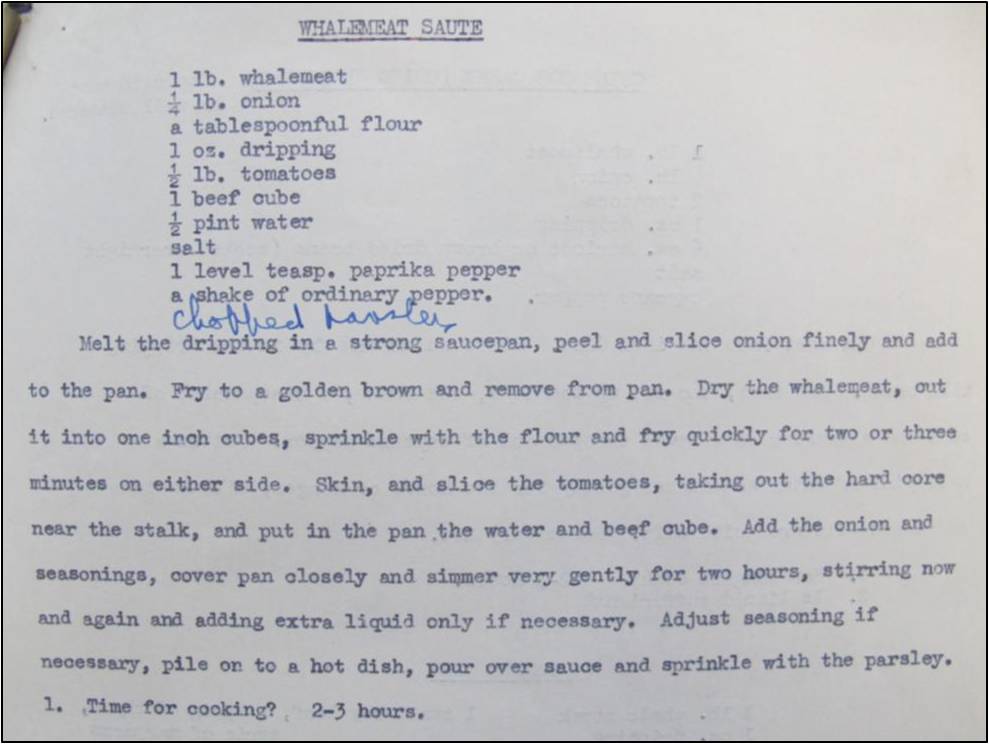

Investigations in to the palatability of various forms of whale meat in MAF 256/89 makes for queasy reading in the late 1940s, with testers asked to comment on the ‘odour’ and ‘flavour’ of different uses of the meat in various recipes. One tester of whalemeat soaked in chlorophyll to improve the smell is described as having spent time in German occupied North Africa and so “knew what it felt like to be in a state of semi-starvation” and “she was quite sure a person in such circumstances would be unable to eat any of these samples.” (The involvement of the Ministry of Food’s ‘Pickles and Sauces section’ later in the file hopefully assisted with the problem).

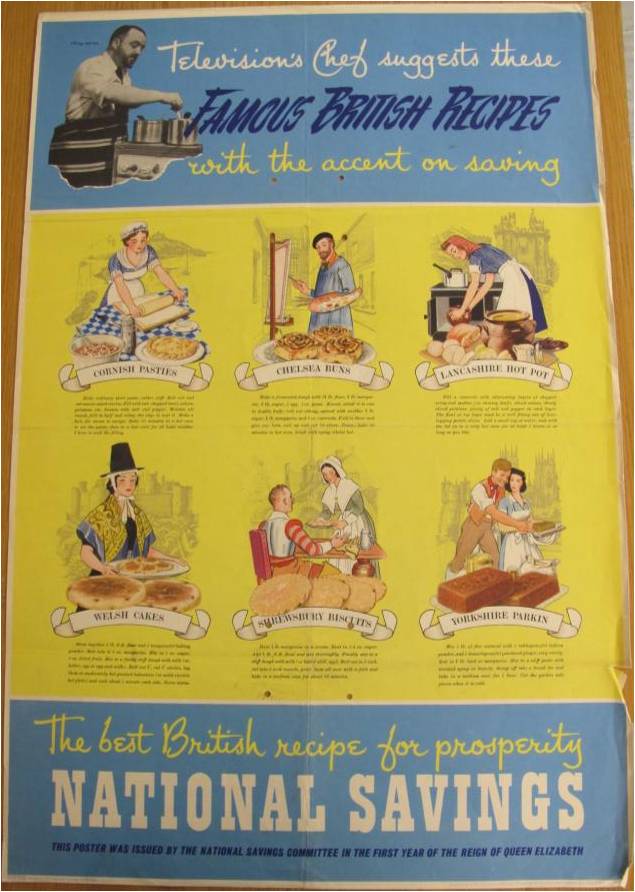

A less stomach-churning example of the government’s involvement in the lives of the general public’s eating habits comes in the form of one of the many National Savings posters from the 1950s in NSC 5/350. A surprisingly early celebrity chef, Philip Harben, suggests the various national bakes as cheap ways of feeding the family and saving money. You’ll notice the role of women in these images, a classic example of the National Savings poster design from the time.

“The best British recipe for prosperity – National Savings”: illustrations of famous British recipes. 1952. (catalogue ref: NSC 5/30)

And finally for now, a book of ‘tested recipes’ in MAF 102/9 for work canteen cooking in the 1940s provides advice on how to best provide balanced and varied meals with limited or rationed ingredients. This advice includes “Clean plates are a compliment to the cook” and “Well served vegetables sell themselves.”

I feel an Archives banquet coming on…

I have to admit that I read the additional line in the Whalemeat recipe as “Chopped Hamster” at first – maybe that would have improved the taste no end ….

Hi Bruce,

Now that would have been an archival discovery!

Thanks!

Jenni

The whalemeat must have smelled nice (I think not!) whilst it was cooking for two to three hours, a bit like washing clothes the old-fashioned way. Philip Harben was always good to watch and less forthright than Fanny Craddock. I was half-expecting Magnus Pike to appear on the blog.

Those interested in more ‘food in history’ might want to check out this year’s Anglo-American Conference of Historians, to be held at the IHR/Senate House in central London, 11-13 July 2013 (further details at http://anglo-american.history.ac.uk/) where there are panels dedicated to exploring workhouse diets in the long eighteenth century, austerity eating, wartime foods, medieval archaeology and much more, alongside all the best in food studies publishing from the academic presses.

Hi David,

Yes, I don’t think the whale meat recipes are going to be top of my list to try! Interesting you remember Philip Harben – no sign of Fanny Craddock in my research so far, but she may appear further down the line…

Jenni

Hi Sara,

Many thanks for highlighting this – it sounds brilliant. As I say, there is certainly a lot of material here on workhouse diets in particular, so the conference will be very relevant.

Jenni

[…] England attempted to use whale as a substitute for more common types of meat, too, but it never really got beyond the planning stages. By the late 1940s, food testers were being recruited to try whale to see if it was going to be a palatable option. It wasn’t. In fact, National Archive documents say that it was derided by a tester who had spent some of the war years in German-occupied North Africa; he knew what starvation was, and he was also sure that even starving people wouldn’t eat it. […]