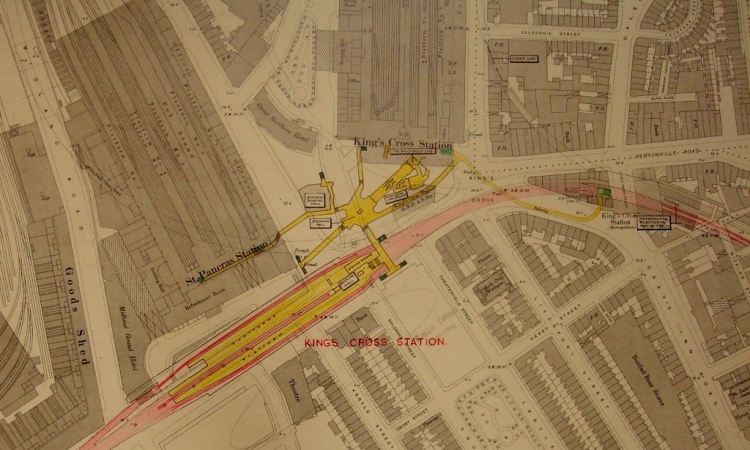

Detail of Ordnance Survey 1:1,056 sheet London VII 33 (1922 edition), annotated in 1947-1948 to show the London Underground Metropolitan Line. (Document reference OS 7/5)

Some colleagues and I recently visited the Mind the Map exhibition currently on at the London Transport Museum. This exhibition explores the role of transport maps in art and everyday life, and it inspired me to choose a set of maps related to the London Underground as the subject of this blog post.

The London Underground (nicknamed the Tube[ref] 1. Although, strictly speaking, only the deeper sections of the system are ‘tube’ tunnels (the rest runs above ground or in wider, shallow tunnels), when Londoners say the Tube, we mean the whole network. [/ref]) is the oldest metro system in the world. The network’s map is a design classic that has influenced transport mapping throughout the world. It is a topological map: unlike most ordinary maps, it deliberately distorts distances and directions so that it can show the different lines and their connections more clearly, because these are what passengers really need to know.

Just as it isn’t necessary to mark the positions of streets or buildings on the Tube map, there is no need for an ordinary street map to show the positions of underground tunnels. For some purposes, though – such as planning a civil engineering project – it can be useful to see both kinds of information on the same map.

In the late 1940s, Ordnance Survey (the national mapping agency of Great Britain) considered the question of whether it would be useful and practicable to show underground railway lines on its large-scale[ref] 2. A large-scale map is one that is relatively ‘zoomed in’, as opposed to a small-scale map, which is relatively ‘zoomed out’. [/ref] maps of London. Up to that point, Ordnance Survey’s 1:1,056-scale maps had shown railways running above ground or in ‘cut-and-cover’ tunnels just below ground level, but not lines running deep underground.

To help them make the decision, Ordnance Survey staff obtained detailed information about all of the lines and stations from the London Passenger Transport Board, and they drew these details onto copies of the existing 1:1056-scale maps. For clarity, they produced a separate set of maps for each line instead of drawing the whole network onto the same set of maps[ref] 3. As well as the London Underground lines, they created sets of maps showing the Waterloo and City Line (which was then run by British Rail), the Kingsway tram tunnel and the Post Office Railway. [/ref].

Ordnance Survey initially decided not to try to show underground tunnels on the new 1:1,250-scale maps of London that it was producing to replace the old 1:1,056-scale sheets. There were three reasons for this:[ref] 4. See file OS 1/135. [/ref]

1) It was impossible to show all of the necessary detail clearly, especially as the maps were to be printed in black and white. Attempting to do so would have made the maps look overcrowded and prevented users from seeing the detail that they needed.

2) It would have created a precedent for showing other underground features, such as sewers and water pipes. Such information would have been time-consuming to obtain and made the appearance of the finished maps even more overcrowded.

3) There was very little evidence that users needed or wanted this kind of detail to be shown on ordinary maps. Planners or engineers who did need to know exactly where underground tunnels were could ask the London Passenger Transport Board, just like Ordnance Survey itself had done.

A few years later, however, Ordnance Survey partly changed its mind and decided that it should start to show the shallow, cut-and-cover tunnels (but not the deep-level tunnels) on the 1:1,250-scale maps. The annotated maps for the relevant parts of the network proved to be a useful source of information for the cartographers preparing the published maps.

Ordnance Survey kept the annotated maps for the whole network and, in 1968, it passed them to the Public Record Office (which is now part of The National Archives) as record series OS 7.

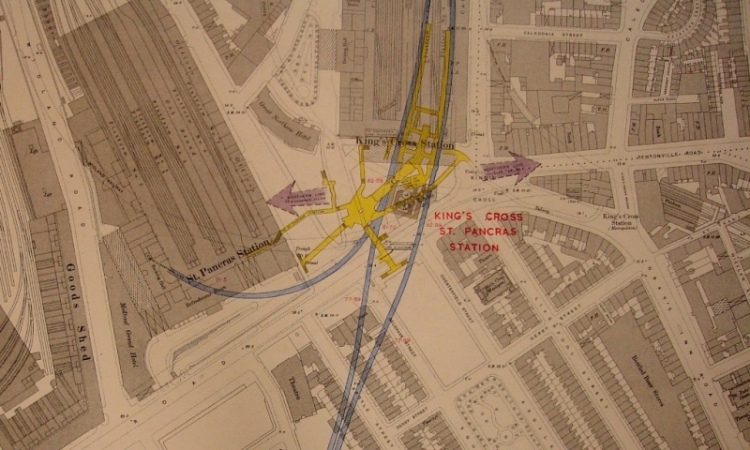

Another copy of sheet London VII 33 showing the Piccadilly Line. (Document reference OS 7/11)

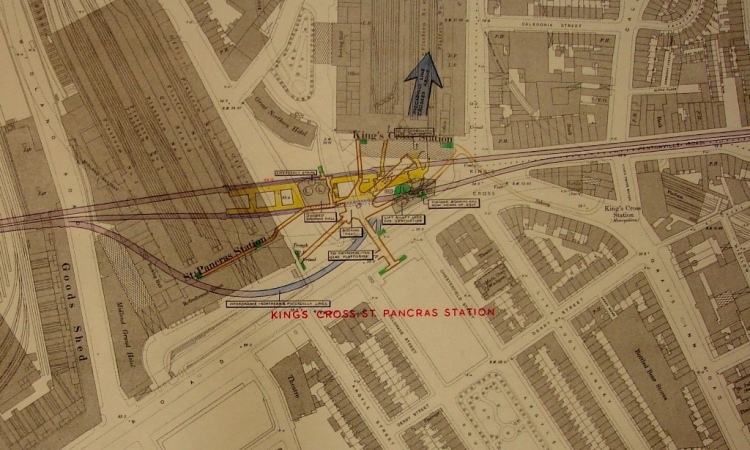

To illustrate this blog post, I’ve chosen three maps showing Underground lines running through King’s Cross St Pancras station (see above, below and at the top of this page). The printed above-ground information is the same on all three but the handwritten and hand-drawn below-ground information is quite different on each one.

Another copy of the same sheet showing the Northern Line. (Document reference OS 7/8)

If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, I’d like you to do two things. Firstly, next time you look at a map, remember that it doesn’t show you everything: it only shows what its makers decided to put on it. Secondly, next time you travel on an underground railway, please spare a thought for the world above your head.

What next?

Learn more about maps at The National Archives.

Read our brief guides on researching railway companies and railway workers.

Elsewhere on the web

Explore a selection of historic posters with map designs on the London Transport Museum website.

Discover a variety of alternative Tube maps via the Londonist website.

Offline

Read Mr Beck’s Underground Map, by Ken Garland (available from The National Archives’ bookshop).

Do you have articles on the Blackwall Tunnel – people who worked on it, we’re injured during the construction, etc?

Hi Cathy

As far as I know, the Blackwall Tunnel was commissioned by a body called the Metropolitan Board of Works rather than by a central government department. The Board’s responsibilities were taken over by the new London County Council (LCC) before the tunnel was actually built.

The LCC’s records are held at London Metropolitan Archives so I’d suggest trying there first.

http://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/Corporation/LGNL_Services/Leisure_and_culture/Records_and_archives/

Good luck with your research.

Great post, thanks Andrew! It would be amazing if the maps could be digitised (if they haven’t been already) and made available online. Are there any plans to do so?

Hi Rebecca

Thank you for your interest.

We don’t have any plans to digitise these maps at the moment but I’ll certainly pass your suggestion to my colleagues who manage our digitisation programme.

You are welcome to visit us to look at the original maps. Visitor information is available on our website at: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/visit/