Bosnian stamp issued on June 28, 1917, to commemorate the third anniversary of the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand and Archduchess Sophia. Image courtesy of James Cronan.

On this day exactly 100 years ago, Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria, and his wife Sophia, Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated in Sarajevo, Bosnia. Franz Ferdinand was the nephew of the ageing Emperor of Austria, Franz Joseph, and heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne.

How did it happen?

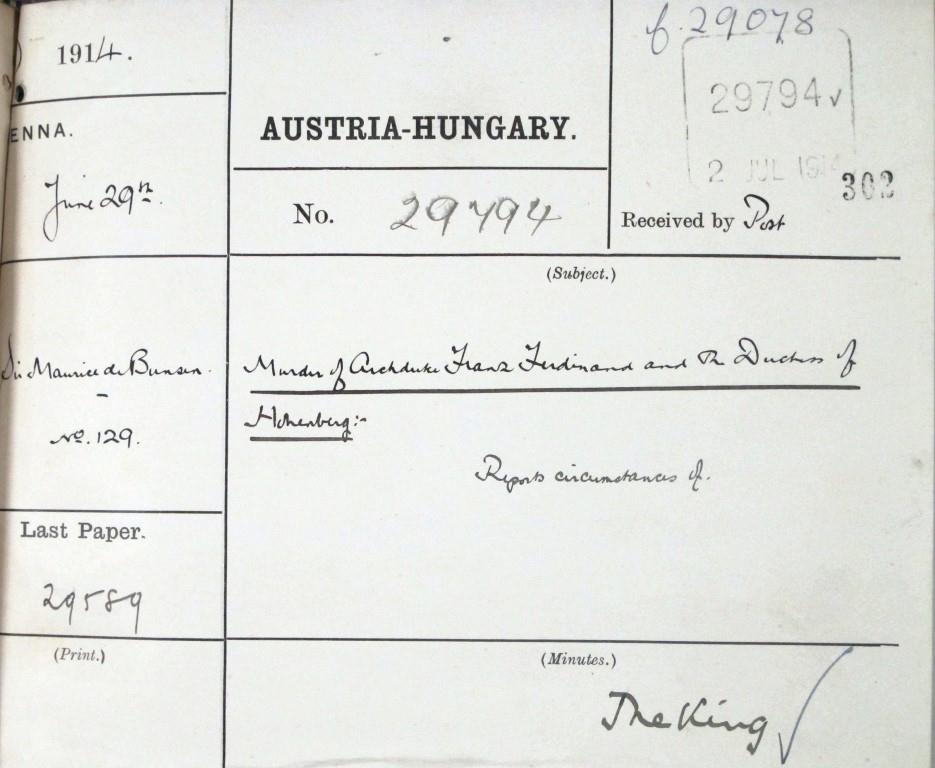

The attack took place on a Sunday afternoon. Initially news came through to the Foreign Office at 6pm via a despatch from John Francis Jones, British Consul in Sarajevo, with very limited information. Clearer news came through on Monday 29 June in a despatch from Sir Maurice de Bunsen, British Ambassador in Vienna to Sir Edward Grey, the British Foreign Secretary. He wrote:

‘Yesterday, Sunday June 28th, His Imperial Highness, after attending mass at Ilidze, proceeded by train, with the Duchess, to Sarajevo, as arranged, for the purpose of making a progress through the town and receiving loyal addresses. On their way from the station to the Town Hall the official account states that a bomb was thrown at them (by Nedeljko Cabrilovitch) but was warded off by the Archduke, exploding immediately behind the Imperial motor car and wounding slightly the two officers who occupied the next car, and more or less seriously some 20 persons in the crowd of onlookers. At the town hall speeches were exchanged between the Burgermeister and the Archduke, the latter expressing his satisfaction at the cordiality of his reception and alluding to the failure of the dastardly attempt on his life.

Despatch from Sir Maurice de Bunsen to Sir Edeward Grey, British Foreign Secretary. FO 371/1899 file 29078 paper 29794

Undeterred, it is said by suggestions that it would be wiser to abandon the remainder of the programme, His Imperial Highness and the Duchess proceeded in the direction of the Town Museum, or as some accounts have it of the hospital to which the wounded had been carried after the bomb outrage.

A man (Gavrilo Princip) ran in from the crowd and fired rapidly several shots from a browning pistol into the car. The Archduke’s jugular vein was severed and he must have died almost instantaneously. The Duchess of Hohenberg was struck in the side and expired immediately after reaching the Konak to which both were carried…. A few steps from the scene of the murders an unexploded bomb was found. It is presumed that it was thrown away by a third conspirator, on perceiving that the second assault had been successful.

The news of the murders was broken about midday yesterday to the Emperor at Ischl, where His Majesty had arrived only the day before. His majesty has thus lived to see his nephew and heir added to the list of his nearest relations who have died violent deaths. His Majesty returns to Vienna today. He has made a most happy recovery from his most recent illness.’

Why was the Archduke there?

The Archduke was in Bosnia to attend a series of mountain exercises by part of the 15th and 16th Army Corps, which took place on Friday 26 June and Saturday 27 June to the south of Sarajevo. Just the previous year he had been appointed Inspector-General of the Austro-Hungarian Armed Forces. As part of the visit the royal couple had been invited to open the state museum in its new location in the Bosnian capital, Sarajevo. Both the manoeuvres and the state visit to the capital had been widely reported in the Austrian and Bosnian press.

Why did it happen?

Gavrilo Princip and his co-conspirators were members of Mlada Bosna (Young Bosnia), a group of Serbs, with some Bosnians and Croats who believed in a unified Yugoslavia, free from the yoke of Austrian rule. The Archduke’s uncle, the Emperor Franz Joseph, had survived an assassination attempt by The Black Hand. This was a Serbian movement for the liberation of the southern Slavs from Austro-Hungarian rule and the creation of a Greater Serbia, who were said to have recruited Princip and his fellow assassins. That Sunday, the day on which the assassinations took place, was also the 525th anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo, in which the Serbians had been heavily defeated by the Turks. What would normally have been a day of national mourning had become instead a national celebration in Serbia and for Serbians in Bosnia and Croatia, following the defeat of the Turks by the Serbian Army in 1912 and the regaining of Serbia and Old Kosovo.

Continuing his despatch, Sir Maurice de Bunsen reported that:

‘The Archduke is said to have been warned in vain against undertaking his projected journey, and to have himself attempted to dissuade the Duchess from meeting him in Bosnia. Her Highness was however determined to share the danger with her husband.’

What happened to Gavrilo Princip and his co-conspirators?

Twenty five men identified as conspirators were apprehended and were tried in October 1914 for conspiracy to commit high treason. Of these, 16 were found guilty and nine were acquitted. Five defendants received death sentences and 11 were sentenced to terms in prison. Princip was less than a month short of his 20th birthday, the age at which the death penalty was applicable under Hapsburg law. He was sentenced instead to twenty years in prison, the maximum sentence for someone of his age. He was kept in a small cell in the military fortress of Theresienstadt (now Terezin) in what is now the Czech Republic, where he died of tuberculosis and malnutrition on 28 April 1918, less than seven months before the end of the war.

The ‘what if’ question

If the Archduke had not been assassinated in Sarajevo would the First World War have taken place?

What is certain is that the assassination set in train a whole set of diplomatic manoeuvres that were to become known as the July Crisis, each bringing the prospect of war ever closer. Austrian diplomats effectively accused the Serbian government, and by association the Serbian people, of complicity in the assassination. A ten point ultimatum was placed on Serbia that amounted to a loss of fully independent law making and sovereignty. Treaties, alliances and ententes drew together what would become the two opposing factions in the First World War, the Allied Powers and the Central Powers. On 28 July Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia and on 1 August Germany declared war on Russia; on 3 August Germany declared war on France and on 4 August it invaded neutral Belgium. It was this, it seems ,that forced the hand of the British Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, providing the ‘casus belli’ that would send Great Britain, and by extension the British Empire, into the horrors of the First World War.

Marking key stages or milestones in the July Crisis, The National Archives will issue a series of five blogs covering the Austrian Ultimatum of 20 July, Sir Edward Grey’s attempts at intervention on 23 July, the Austrian attack on Serbia on 28-29 July, general troop mobilizations on 1 August and the violation of Belgian neutrality and Britain’s declaration of war on 4 August.

The Foreign Office are also tweeting in real time the events of the July Crisis. Look out for the tweets from @WW1FO starting on 28 June.

[…] Two bullets that changed the course of history […]

Thank you for this well written, informative article. Fascinating commemorative stamp of the Archduke and Archduchess. The article brought the whole espisode to life for me with details on how and why it happened, what happened to the perpetrator and the intriguing ‘what-if’ section.

[…] alliances and agreements, rising nationalism and multiple other factors were catalyzed by the tragic events in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914. By August, the world was at war. In the September, 1914 issue of the RED CROSS® Messenger, a […]