2013 is an important year for my host organisation, the Borthwick Institute for Archives, based at the University of York. The year simultaneously marks both the 50th anniversary of the University’s establishment, and the 60th anniversary of the Borthwick’s foundation. The latter became a part of the former in 1963, on occasion of the university’s opening.

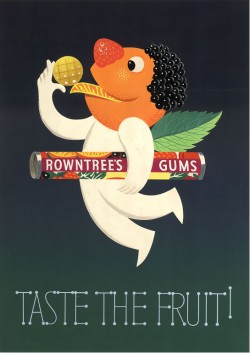

Formed in 1953 as a repository and public research centre for the vast ecclesiastical archive of the Archdiocese of York, the Borthwick has since acquired material of increasingly broad and diverse origins. No longer renowned solely for its extensive church records, dating as far back as the 13th century, the Borthwick now boasts holdings that range from the archive of internationally acclaimed playwright Alan Ayckbourn, to those of the famous confectionery firms, Rowntree’s and Terry’s. Other highlights include the secret war diaries of E. F. L. Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax, who served as Foreign Secretary and British Ambassador to the United States during World War II, and the archive of The Retreat, a Quaker-founded hospital for the mentally ill, established in 1796, which pioneered humane, progressive therapies at a time when most other asylums were treating their patients as little more than animals.

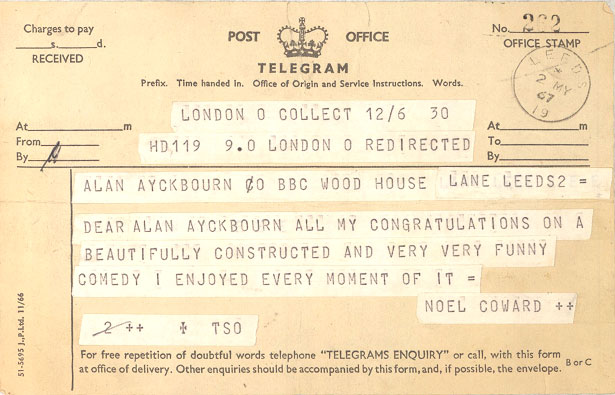

Telegram from famed playwright Noël Coward to Alan Ayckbourn on the premiere of his play, Relatively Speaking (1967)

A major project that my fellow trainee, Zoe, and I were charged with during this past year was the creation of an exhibition to grace the cabinets of the Borthwick’s display area. Our remit was broad and our limits were few; our only criterion was that the exhibition should be a display exclusively of surrogates, and that no original documents should be used. This was to be a stand-by, ‘conservation-friendly’ exhibition that could be reinstalled on multiple occasions in the future; an interim display that could be briskly and relatively easily deployed between exhibitions of actual archive material, so that the cabinets were never left empty.

It was a project that we were given relatively early on in our time at the Borthwick. All the key decisions, from the exhibition’s inception to its conclusion, were to be entirely ours. It was an exciting assignment, but also a daunting one. During those initial months of our traineeship, we were still largely unfamiliar with the extensive archives at our disposal, and it was difficult to know where to start. Without any training or real guidance in how to develop and curate an exhibition, we relied on our own experience as visitors of museum and gallery displays to influence the decisions we made. We discussed our responses to exhibitions we had seen, what we thought worked and what didn’t, and used the conclusions we arrived at as a launch pad from which to proceed.

Given our exhibition was to be a resource that could be reused in the future, we resolved that its subject matter should be based around a broad theme rather than a specific topic. As such, we settled upon creating a display that would showcase some of the various highlights of the Borthwick’s collection. We hoped that this would not only make for an exhibition of continuing relevance to the archives, but would also provide a visually appealing answer to the perennial question customers ask of searchroom staff: ‘What material do you hold here?’

We set ourselves the somewhat demanding task of presenting 11 different archives within just eight cabinets. We wanted to provide a snapshot of the Borthwick’s exemplary holdings, and a taster of the broad variety of material available to researchers. At the same time, we were reluctant to devise an exhibition composed predominately of the oft-used and overfamiliar records that usually get wheeled out for promotional press releases, projects, and events. It was our mission to locate fresh, interesting, and affecting material that remained unseen even by some archivists at the Borthwick.

Uncovering the hidden treasures of archives we knew very little about was certainly challenging. We spent hours on end trawling through catalogues and pulling out boxes at random in the chilly strongrooms, until the eventual loss of feeling in our hands and feet forced us to retreat elsewhere to defrost.

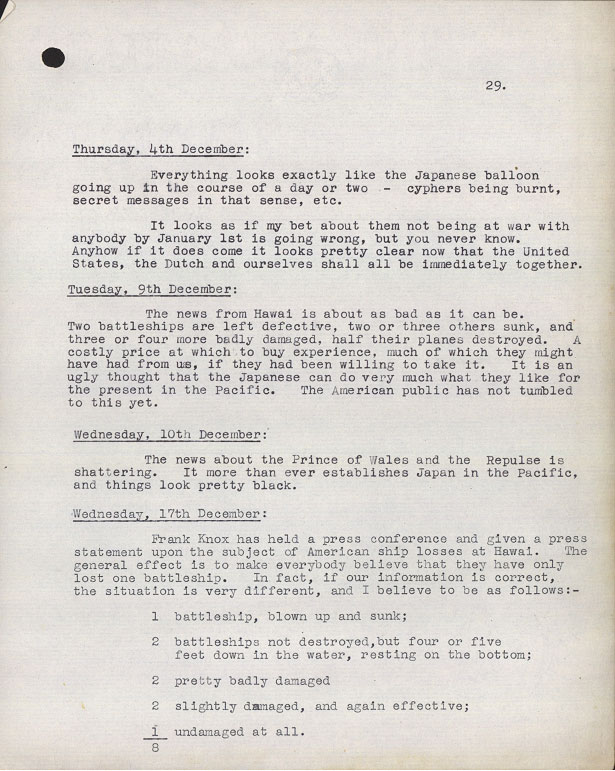

A page from Lord Halifax’s secret war diary, which he kept whilst serving as British Ambassador to the United States (1941)

We worked on the simple principle that if we found a document to be particularly interesting, then in all likelihood, other people would too. In making our selection, we not only considered the content and subject matter of material, but also its visual appeal and eye-catching potential. Many archival institutions, by the very nature of their holdings, struggle to inject their exhibitions with a brightness and vividity, and this was a difficulty we encountered too. In response, we strove to temper the largely brownish hues of our paper and parchment records with colourful documents whenever possible.

Once we arrived at a shortlist of documents to represent each of our chosen archives in the exhibition, we then had to formulate a layout for every cabinet shelf and display case. To prevent damage to the archive material through excessive handling, this was achieved using an array of pieces of cardboard of various sizes in lieu of the actual documents. We spent many an afternoon juggling these blank bits of cardboard, trying to settle upon the best way to display the archive material and attempting to finalise which of our selected documents to exhibit and which to discount, all the while dredging the depths of our imaginations to picture how the finished product might appear.

The documents that made the final cut for the exhibition were then digitally scanned and high-quality prints were made of the images. The prints were subsequently passed to the conservation department to be boarded and trimmed as appropriate. Although ours was to be an exhibition of surrogates, we wanted to represent the original archive material as accurately and realistically as possible. To this end, we reproduced everything true to size and strove to achieve prints as close to the documents’ actual colouring as possible. The conservation department, too, did an excellent job not only of recreating the pamphlets and books we had chosen to exhibit, but also of intricately trimming the prints so that the surrogates retained the tattered, rough edges of their originals.

It was then to the laborious task of research, and writing the captions and information boards for the exhibition. As I mentioned previously, we had set ourselves the challenge of showcasing 11 different archives in just eight cabinets. This made for a great deal of background reading on subjects ranging from the administration and jurisdiction of the Church, to the history of chocolate making in York. We knew that colour and eye-catching imagery would draw people into the exhibition, but realised too that punchy, informative text was needed to sustain that initial curiosity. As such, we scoured numerous books and websites to harvest the best and most interesting information we could find, which we then condensed, with some difficulty, into a few choicely worded captions.

From here, our concerns were primarily aesthetic. We wanted to make the exhibition appealing and accessible to a broad variety of people. Our goal was to create information boards that were clean and sharp in their design, and that featured imagery whenever possible to enhance the visual impact of the exhibition. We researched the recommended fonts and text sizes for use in archive and museum exhibitions, taking care to ensure that visitors would easily and comfortably be able to read our written material. Props were another means by which we maximised our exhibition’s pull; one of my favourite purchases were some multicoloured, disc-shaped plastic beads, which we used to represent convincingly Smarties in the Rowntree’s display case.

After all our hard work, it was incredibly satisfying to finally install the exhibition. From budgetary concerns to equipment failures, and from copyright queries to printing delays, we had encountered our fair share of challenges, but we were pleased with the result of our labours and it was a relief to see that our persistent attention to detail and thorough planning had ultimately paid off.

Reaction to the exhibition has so far has been excellent, and there are currently plans to develop an online version in order to showcase the archives to an even wider audience. It thus seems we succeeded in our mission to create a resource that will remain of use to the Borthwick in years to come — an objective that we are certainly both delighted and proud to have achieved.

Thanks for this interesting post on your process. There is a team of us here at Archives New Zealand working on a large-scale exhibition of our own holdings (including Te Tiriti o Waitangi, a hugely important document). Like yours, our holdings are dauntingly broad! So we’ve developed storylines or themes to act as a lens for what we should select. Hopefully a website will be up soon that you or others can follow.

Thanks again, all good luck with your future projects!

Jared Davidson

Research Archivist, Archives New Zealand

Hi Jared, thanks for your post. I’ll look out for your website; your exhibition sounds intriguing and I’d certainly like to learn more about it.

Good luck with the project!

This is interesting and very worthwhile and I think an online version would help. I was surprised that you had Lord Halifax’s diary on and around the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941 and the Borthwick Insitute was not somewhere I would have expected the diary to be. I think it would help if the sources, i.e. document references were there as it helps us when we would like to look at the documents.

I quite agree about just opening boxes and seeing what is there, the records that are often uncatalogued are the most interesting and surprising like the uncatalogued 18th century Treasury records on David Livingstone at The National Archives in Kew on the attempts by the Royal Geographical Society to find him wherever he was thought to be at the time.

Of course the Livingstone records are for the 19th century!.

Hi David, thanks for your post. Yes, we hope the exhibition will make people more aware of the range of material we have here at the Borthwick. Many people, like you, are surprised to learn we hold certain archives.

I’m sorry the document reference for the Halifax diary was not featured in my post. I did include it with my submission, but it must have been lost somewhere along the way! It’s HALIFAX/A7/8/19, if you visit the Borthwick and wish to look at the document itself.

The other two documents pictured in my post (Ayckbourn telegram and Rowntree’s poster) have not yet been catalogued, so they do not have references.

Hope this helps!

I think it is pretty amazing that these kinds of record could be available on the internet. I think learning history will be much more interesting for children. My cl-husband’s father served in the war and in his 70s became internet savvy. I’ll put him on to this site. I think he will find it very fascinating.

Debbie from Canada

The Canadian Legal Resource Centre Inc.

Hi Debbie, thanks for your post. I agree, the Internet represents a brilliant tool for introducing a broad variety of people, of all ages, to records of historical interest.

Please look out for the online version of the Borthwick’s exhibition, which will hopefully be going live soon!