On 22 April 1917 the Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force captured Samarra, some 80 miles north of Baghdad. There, the military authorities made a discovery that triggered another battle of Samarra: an archaeological one.

In an old building in Samarra the British troops found about 90 cases of antiquities, left there by the German archaeologists who had been excavating the site in 1914, Ernst Herzfeld and Friedrich Sarre.

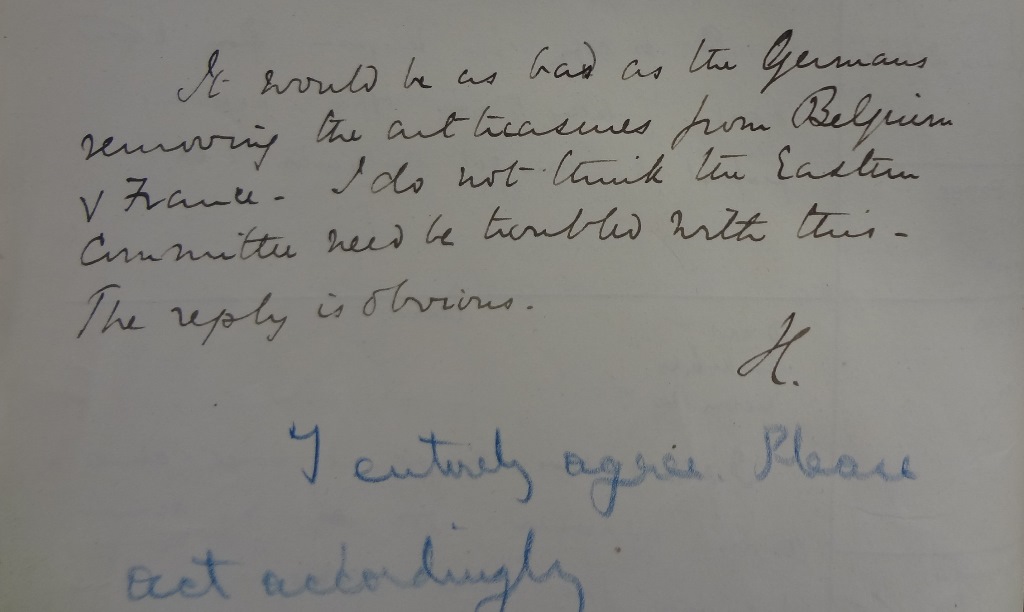

These antiquities came to the attention of the Foreign Office in the summer of 1918, at a time when officials were increasingly aware of the importance of antiquities and ancient monuments. When it appeared that orders had been issued for the despatch of the Samarra antiquities to London, the Foreign Office protested vigorously. ‘It would be as bad,’ they wrote, ‘as the Germans removing the art treasures from Belgium and France’ (FO 371/3410).

The India Office wasn’t very happy either and pointed out: ‘to remove these antiquities from their natural home raises a large question of policy’. They thought the issue should be considered by the Eastern Committee of the War Cabinet (FO 371/3410).

At the end of July the War Office, who thought the cases should be sent to Britain, reluctantly agreed they could remain in Basra, where they had been stored. But they weren’t prepared to go down without a fight and added:

‘The Army Council wish, however, that it may be clearly understood that they have complete authority over all such captures, and that these particular antiquities have been allotted by them to the British Museum Authorities and that this decision will be adhered to.’ (FO 371/3410)

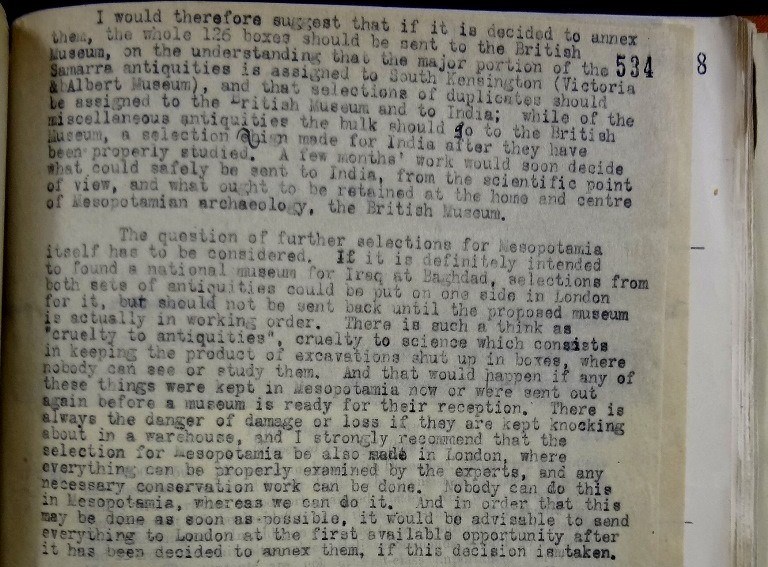

In the summer of 1919 Henry Hall, of the British Museum’s Department of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities, finally opened the cases to examine the artefacts. He made a passionate plea for the antiquities to be sent to London, where they could be studied properly. He wrote:

‘There is such a think [sic] as “cruelty to antiquities”, cruelty to science which consists in keeping the product of excavations shut up in boxes, where nobody can see and study them. And that would happen if these things were kept in Mesopotamia now or were sent out again before a museum is ready for their reception.’ (FO 371/4175)

Passion, however, wasn’t enough. The India Office thought there wasn’t anything in Hall’s report that could justify sending the antiquities to London. Writing in that sense to Baghdad, they suggested it may be time to think about a museum in Iraq itself (FO 371/4175).

Henry Hall’s report, 7 June 1919 (catalogue reference: FO 371/4175)

By 1920, the political authorities in Iraq were getting a bit restless. They didn’t know what to do with the Samarra antiquities: they’d had them for four years, and they wanted them gone. ‘Pressure of space at Basrah,’ they wrote, ‘and other considerations render it desirable that definite decision of their temporary resting place should be reached’ (FO 371/5138).

In November 1920, a group of British archaeologists wrote to the India Office, demanding that Ernst Herzfeld should be present when the cases were opened, whether in London or in Mesopotamia. They understood that ‘the popular hostility to Germany may oppose the sending of an invitation’, but they begged for the matter to be considered as it was the only way not to lose valuable scientific information (FO 371/6362).

- Memorandum by British Archaeologists, 30 November 1920 (catalogue reference: FO 371/6362)

- Memorandum by British Archaeologists, 30 November 1920 (catalogue reference: FO 371/6362)

In February 1921, Winston Churchill, then Secretary of State for the Colonies, authorised the shipment of all the cases of antiquities to the British Museum in London ‘where (…) they might be examined and treated in the presence of Professor Herzfeld, or his deputy’. The Foreign Office protested. They hadn’t been consulted, and it was ‘in entire contradiction with [the policy] that had been pursued by His Majesty’s Government since 1914’. They briefly wondered whether it could all be stopped. The Colonial Office tried to reassure them: the antiquities had been despatched and it was too late to stop them, but there was nothing to worry about. They explained:

‘it is being made clear both to the Acting High Commissioner, Baghdad, and to the Museum authorities, who will take charge of the antiquities while in this country, that the articles will remain the property of Mesopotamia, and that their despatch to England is without prejudice to the question of their final disposal.’ (FO 371/6362)

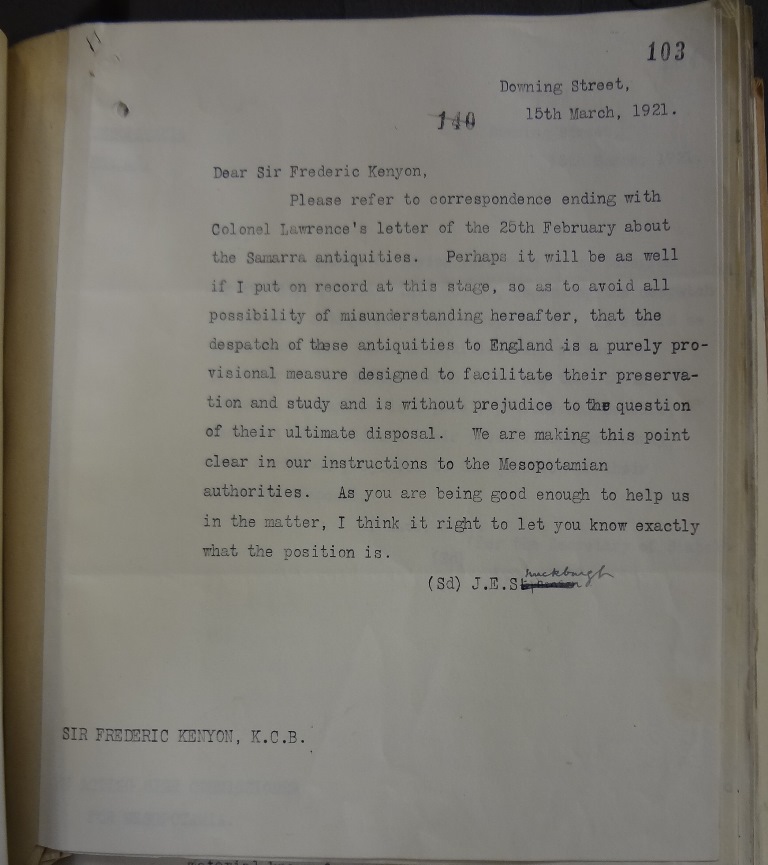

John Shuckburgh, at the Colonial Office, wrote to Frederic Kenyon, the director of the British Museum on 15 March 1921. In order to ‘avoid all possibility of misunderstanding hereafter’, he wanted to make sure Kenyon understood that ‘the despatch of these antiquities to England [was] a purely provisional measure’ (FO 371/6362).

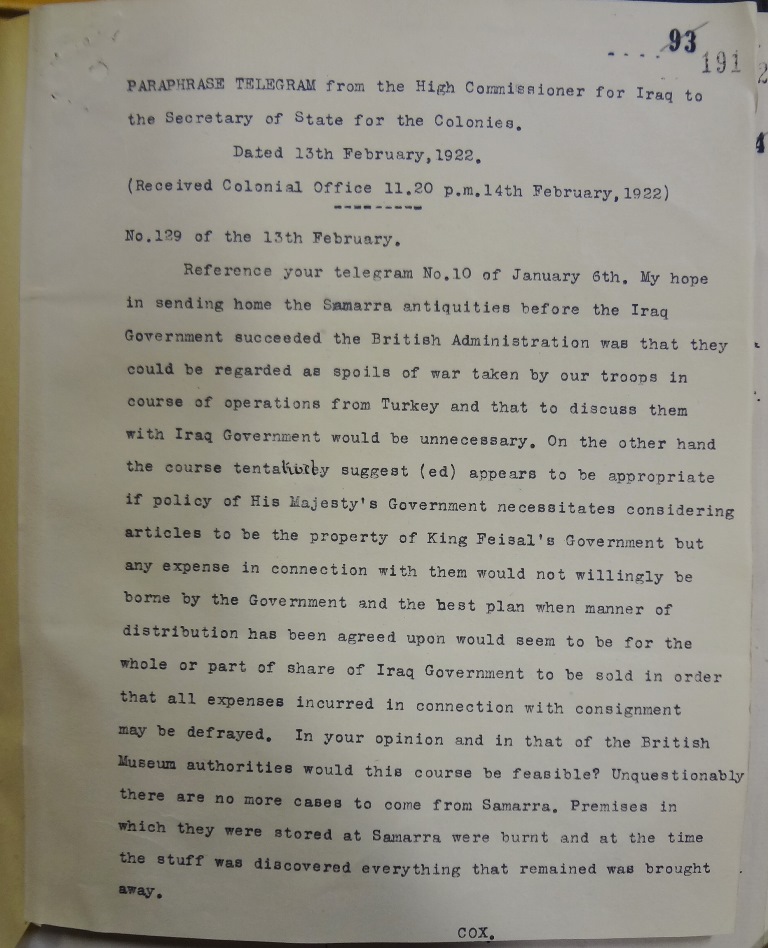

The official reason behind the decision was that the antiquities were rapidly deteriorating and that they needed to be catalogued and conserved. In February 1922, however, Percy Cox gave a less scientific explanation:

‘My hope in sending home the Samarra antiquities before the Iraq Government succeeded the British Administration was that they could be regarded as spoils of war taken by our troops in course of operations from Turkey and that to discuss them with Iraq Government would be unnecessary.’ (FO 371/7797)

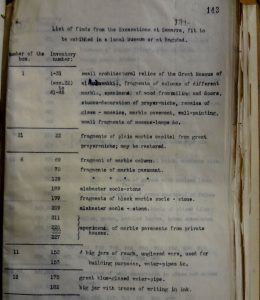

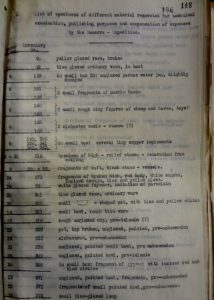

Ernst Herzfeld was granted permission to travel to London in June 1921 and, having examined the antiquities, submitted a report in September. He thought a great deal of the material could be sent back to Baghdad ‘if ever a museum [would] be founded there’ and that the rest could be given to European museums. He begged to be allotted a share ‘for technical examination, publishing purposes and compensation of expenses’ (FO 371/6362).

- Herzfeld’s report, 1921, list of finds from the excavations at Samarra fit to be exhibited in a local museum or at Baghdad (catalogue reference: FO 371/6362)

- Herzfeld’s report, 1921, list of specimens of different material requested for technical examination, publishing purposes and compensation of expenses by the Samarra Expedition (catalogue reference: FO 371/6362)

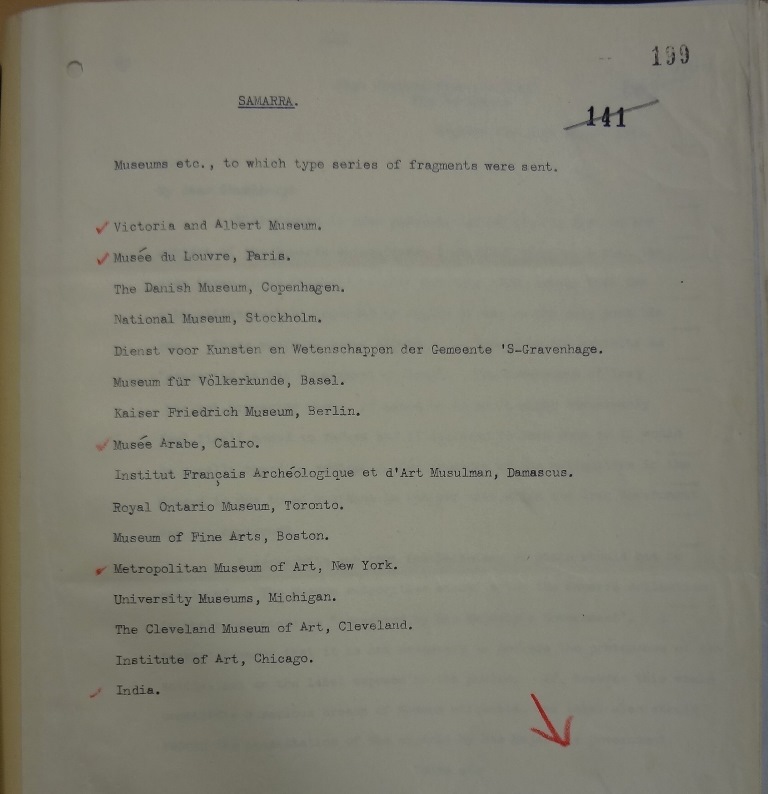

In March 1922, the antiquities were still at the British Museum, where they were taking up a lot of much needed space. Churchill had T.E. Lawrence examine the collection. Lawrence thought everything could be divided up between various museums and that a ‘representative set, in duplicate’ could be kept for Iraq, which should be enough to ‘safeguard its interests’. It was also decided that the Iraqi share would remain at the British Museum who would hand it over ‘to the Iraqi Government in Iraq free of all charges whatsoever, whether for transport, classification, or any other purpose, as soon as they [were] prepared to receive it’ (FO 371/7797).

The Samarra antiquities were then almost forgotten for over a decade. In 1935, in the middle of a struggle to pass a new law of antiquities, the Iraqi government enquired about them, hoping to get them back for the Iraq Museum, which had finally been founded in 1926. Having found out that the objects were at the British Museum and other institutions, they pointed out it was ‘not fair’ and demanded ‘the adoption of measures for the restoration of the antiquities in question to the ‘Iraqi Museum’ (FO 371/18946).

- Note from the Iraqi Ministry for Foreign Affairs, 9 April 1935 (catalogue reference: FO 371/18946)

- Note from the Iraqi Ministry for Foreign Affairs, 9 April 1935 (catalogue reference: FO 371/18946)

The Foreign Office wasn’t terribly up to speed when the issue resurfaced, but they did what we all do – they turned to the archives. A quick check was enough to ‘show that His Majesty’s Government considered that the Government of Iraq had a claim on the antiquities’.

The British Museum wasn’t too pleased. They were concerned Iraq was demanding the return of all the antiquities that had been discovered in 1916 and were now scattered among various institutions. They pointed out that Iraq had ‘no claim on the material beyond the promise that a selection should be given to Iraq when it should be in a position to have it’. They also said the antiquities had been in rather poor condition when they had arrived and had kept deteriorating – to such extent that a curator wrote: ‘it is in fact doubtful whether the cost of transport back to Baghdad is worthwhile, for a small expenditure in excavation at the site would probably produce better results’ (FO 371/18946).

The Foreign Office insisted that the claim was a moral one, and reminded the Museum that it had been agreed the antiquities would be sent back free of charge. The Museum very grudgingly relented and two cases of antiquities were sent to Baghdad, where they arrived on 17 August 1936 (FO 371/20011).

The antiquities arrived 10 years late, the catalogue was missing, and the Director of Antiquities had to battle for a collection that had been stored for his museum. Still, back in 1936, it felt like Iraq had won the battle of Samarra.

As a historian and the father of an archaeologist, I really appreciated this piece. The issue is multifaceted, and this article underlines them, even if just by implication.

Thank you for the post. I plan to share this with my son.

great post