People sometimes comment on the fact that we are called ‘The National Archives’ and not ‘The National Archives of…’ If you look at the Who we are page of our website you will see that ‘The National Archives is the official archive and publisher for the UK government, and for England and Wales.’ Or, to put it another way, some of our records cover only England and Wales, and some cover the whole of the United Kingdom. So far, so good, but then you have to remember that the United Kingdom has changed over time; it came into existence until 1707, with the Union of the English and Scottish parliaments, to which Ireland was added in 1801. Most of Ireland gained its independence under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, and forms of devolved government were established in Scotland and Wales in 1999 with the re-introduction of a Scottish Parliament and the new Welsh Assembly.

For a student of history this is interesting – I was interested enough to take a course called ‘Territory and Power in the UK’ in my final year at university – but it’s also important for a genealogist to know about the history of the United Kingdom and its constituent parts. Two of those constituent parts, Scotland and Northern Ireland, also have their own national archive bodies, the National Records of Scotland (NRS) and the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI); Wales has been entirely under the control of England and its legal system since 1282 and does not have a national archive, but it does have the National Library of Wales.

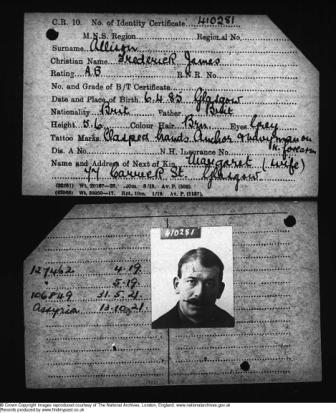

Frederick James Allison from the Registry of Seamen in BT 350

If you have English ancestry you need to work out which records are held locally in county record offices, and which records are here in The National Archives, but if you are researching Welsh, Scottish or Irish families you might also need to work out which national repository you need to consult. People researching their Irish ancestry are often particularly surprised to discover just how many Irish records we hold here, and yet The National Archives rarely features in lists of major resources or websites for Irish research.

The Irish Diaspora is particularly large, since Ireland once had a large population but which dropped dramatically from the 1840s onwards, mostly due to emigration. In 1841 there were 8.2 million people in Ireland, compared to England’s 15.9 million, but by 1911 this had fallen to 4.4 million while England’s population had more than doubled to 36.1 million. As a result, there are far more people outside Ireland with Irish ancestry than there are in Ireland. They may not be aware, at least to start with, that Ireland was part of the UK during the time period they are researching. I have no such excuse, having lived in the UK all my life, but I didn’t realise just how much we had until I started gathering material for a talk on Irish records in The National Archives, which I first delivered about 8 years ago.

As a general rule, records that relate exclusively to Ireland or Scotland are likely to be held there, either in a local archive or at NRS, PRONI or the National Archives of Ireland in Dublin. Records of UK-wide bodies that include Scottish or Irish material are more likely to be held here. For the genealogist the main areas of interest will be records of the armed forces and the merchant navy, along with other services like the coastguard, Customs and Excise and dockyard employees. This is particularly good news for people like me whose ancestry is entirely Scots and Irish, but who live within easy reach of Kew (or, as in my case, work in the building where all this wonderful stuff is held. To date I have found records of my own family in the army, the Royal Navy, the Royal Marines and the merchant navy, including First World War unit war diaries and a detailed account of an enquiry into the sinking of the ship on which my great-great-grandfather was killed.

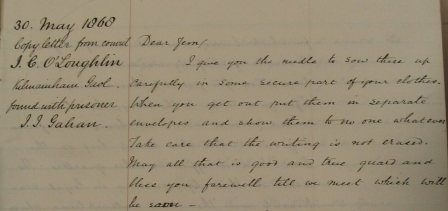

CO 906/32

Of course it’s not quite that simple. We also have some records for the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man, which have never been part of the United Kingdom, but are dependencies under the British Crown. The census in those islands was administered by the Registrar General for England and Wales, so they are part of our census holdings. In fact the 1841 and 1851 censuses for Scotland were also conducted by the English Registrar General, but the records were transferred to Edinburgh over a century ago. Then there are some sets of records that are exclusively concerned with Scotland or Ireland, but which are held here anyway. For Scotland there is a wealth of records relating to the Jacobite risings of 1715 and 1745 including lists of prisoners and details of their trials. For Ireland there is a large collection known as the ‘Dublin Castle’ records, concerned with the British administration in Ireland up to 1922 in record series CO 904, and much more in other record series, including service records for the Royal Irish Constabulary in HO 184. Dr Alice Prochaska’s book ‘Irish history from 1700: a guide to sources in the Public Record Office’ (British Records Association 1986) has long been out of print, but is the most comprehensive guide you could hope to find.

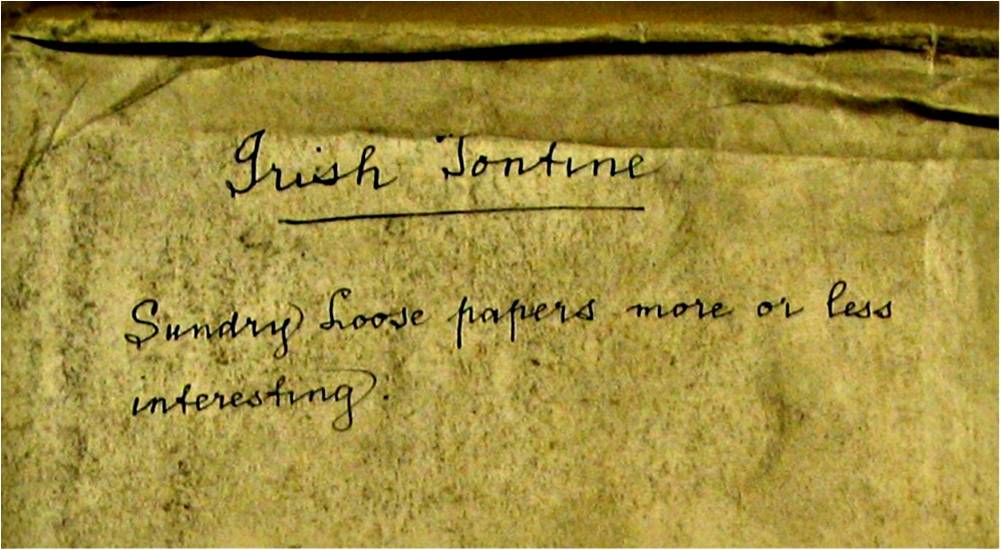

Perhaps my favourite series, though, is one that looks as though it is Irish, but isn’t. This is NDO 3, National Debt Office: Irish Tontines (1773 to 1777). A Tontine is a kind of lottery, and the records contain lots of copies of baptism, marriage and burial certificates. The only snag is that most of the people who subscribed to the Irish Tontines weren’t Irish, so this isn’t quite the goldmine it might first appear. It does, however contain one of the best, if least helpful, catalogue descriptions I have ever seen ‘NDO 3/49 Packet of sundry loose documents – more or less interesting’

NDO 3/49 catalogue description as taken from the original document

I have never liked and still do not like the term ‘The National Archives’ and the Public Record Office was in my view better at describing the archive. Ireland is a bit difficult as a few papers for the Republic are in Belfast and vice-versa. It will be interesting if (hopefully) Scotland becomes independent (as someone with Scottish ancestry) whether the Army records will in future go to TNA or not.

Whilst Scotland has its own archive and for a number of family history records ‘Scotland’s People’ which is probably the best thing that there has been since the invention of the wheel (you don’t have to order certificates over a large amount of time at over £9 plus each time) but some of the records especially for Orkney and Shetland are held there and not in Edinburgh. TNA does have a lot of information in the records of the Jacobite rebellions with witness statements and a copy of Flora MacDonald statement on how she got Bonnie Prince Charlie away from Scotland. TNA does, because there was a bigger government issue, have records of events which were Scottish like the implementation of UK-wide measures following the Glen Cinema disaster in Paisley in December 1929 when the doors of the cinema were locked.

It is in my view interesting how TNA have a modern building whereas the National Records of Scotland still retains their original buildings and makes it feel a more friendly archive, I know some people find visiting TNA a bit overwhelming and that is after trying to work out where the information is on the website.

Thanks for an excellent explanation and history lesson, Audrey.

Although it is appears to be a daunting institution I have found that the staff of TNA are extremely friendly and helpful when this poor old colonial visits from downunder.

Audrey, in relation to sources re Ireland earlier than those covered in Alice Prochaska’s book, I suggest you look at Philomena Connolly’s Medieval Record Sources, in the Maynooth Research Guides for Irish Local History series. It is still available from an online book shop I had probably better not name – and I have a copy you can borrow.

On the matter of when the UK came into being, I seem to remember that the union with Scotland brought Great Britain into being and it was the 1801 union with Ireland which brought the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland into being. Now, of course, it is the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Strange that we have a Great Britain Olympic team which of course includes competitors from Northern Ireland rather than being called a UK team.

Strictly according to the official IOC name it is Great Britain and Northern Ireland, but abbreviated/branded as Team GB

The official IOC name may be as you suggest but it is still not a UK team since it includes competitors from the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man, which are not part of the UK. Given everything, perhaps ‘Team GB’ was a reasonable compromise!

True, so far as IOC is concerned, it’s jsut which National Organising Committee so affiliate to which really matters

Hopefully by the time of Rio the IOC will agree to a seperate Scotland team after independence.

More likely to end up a “Independent athletes” like the athletes from Netherlands Antilles and South Sudan in London – it takes quite a while for a NOC to be ratified.

Great reading. It is so difficult to research my ancestry being from n Ireland.

And finding census for this country is difficult as a lot seems to be destroyed.

It is not free as some sites suggest but I feel it should be easier to get online records and free ofcourse .We are in a difficult situation here in n Ireland with the country of Ireland separated the way it is and the Governments have a duty to put the records online for all Ireland census.