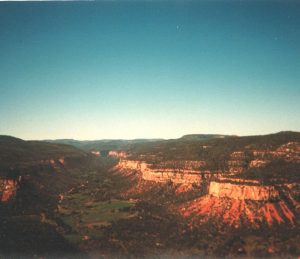

In 1999 a daring young man with brilliant blue eyes stood atop the Uncompaghre Plateau in Western Colorado. Jaw held tight to stop his quivering bottom lip, he looked up to the azure sky and fought back the tears.

‘Sorry kid. The Brontosaurus doesn’t exist.’

In five simple words (and one Latin one) the last remnant of his childhood lay dashed upon the hard dirt floor of the Dry Mesa Quarry.

That young palaeontologist was me and while my site director did at least offer gentle words of condolence for my loss. I was left wanting.

‘How could there not be a Brontosaurus? Why were people not angrier about this? And if Brontosaurus didn’t exist… whose giant shin bone was I currently wrapping in plaster?’

Brontosaurus excelsus was first described by palaeontologist Othniel Charles Marsh in 1879. To do this Marsh, like many palaeontologists of his time, had to indulge in a certain amount of ‘cut and paste’. The skeleton of Brontosaurus was incomplete, and whilst it looked similar to the earlier discovered Apatosaurus (1877), he was convinced it was a new species.

As it turns out what he had actually done was put the body of an Apatosaurus with the head of a Camarasaurus. Two already identified and totally distinct species – one of which Marsh had described only a year earlier!

Shin bone of an Apatosaurus with Sharpie pen for size reference

Marsh didn’t do this out of malice or mischief (well may be a little bit). Dinosaur bones locked in sediments, which form rock layers, are mushed (that’s the technical term) around over millions of years. So fossils that may now be only a few feet apart, might never have had any relation with one another when they were first laid down. Correctly interpreting the context of the fossils in such circumstances still presents problems to this day. Marsh had no option but to guess based on the way the information was laid out in front of him.

As I’ve since discovered; working with digital information is not that different from digging up dinosaurs. It is all too easy to lose the structure and context of documents and folders particularly when moving them. Once it’s lost there’s a real risk that unrelated information can get mushed (also a technical term for digital information) together making it much harder to not only find information; but then trust that what you have is the right information.

So, the next time you’re asked to move digital information around, remember Othniel Charles Marsh and the importance of context…

Bravo. It sounds as if in a nliecy subtle way your lessons raise the issue of what knowledge is (and it is odd that most schools try to impart knowledge without ever encouraging students to think about what it is). The ideas that all knowledge is provisional and fallible, and that every idea has a history, and that as learners we belong to a particular tradition these are ideas that need to be highlighted somewhere in the curriculum. Just one question: How did James Cook keep those lemons fresh?

Hi Carmela

Thanks for the comment! I agree that we sometimes forget what we learn for. It looks like our message made sense to you, which is a good thing – please keep an eye for future bolgs from our team!

I’m afraid I have no idea how james Cook kept his lemons fresh – my area of study is a bit “earlier” than that.