Towards the end of 1917, the following letter was sent to Directors of Recruiting in all regions for transmission to Deputy Commissioners of Medical Services and Assistant Directors of Recruiting (NATS 1/769):

‘In the future when recruits are examined, the Deputy Commissioner of Medical Services will complete a nominal roll of all those examined who are found to be suffering from Venereal Disease before they are passed to a Reception Depot or Recruit Distribution Battalion. This roll, headed in red ink “Venereal Cases,” will be handed to the Assistant Director of Recruiting and transmitted by him with the draft to the Officer Commanding the Reception Depot or Recruit Distribution Battalion, as the case may be.’

Venereal disease (VD) was an issue for the forces during the First World War, on all sides. Documentation held here highlights that the figures for the period of August 1914 – June 1917 show that the rate of admissions to military hospitals for VD was 34 per thousand, per annum. In France, the admission rate for the British Army was approximately 24 per thousand per annum; it was 32 per thousand in Egypt.

These figures were supplied by the Army Medical Department and covered all troops, Regulars, Territorials and overseas. We do have a further breakdown for the overseas troops for the first 6 months of 1917, which were as follows (again this is per thousand):

- Australia – 144

- New Zealand – 134.2

- Canada – 49.2

Treatments and the medical side

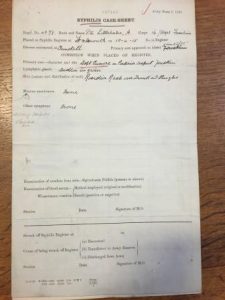

MH 106 holds two boxes relating to VD in the period 1914-1915. The majority of cases seem to be for either syphilis or gonorrhoea, but medical case sheets are also contained for those who develop further issues relating to the contracting of VD.

The medical case sheets held within offer a wealth of information with regards to symptoms VD, and occasionally how the man came to be infected. Many of these just say that he had recently been in connection with ‘a girl’. But some of them are more inventive – for example, the man who was suffering from gonorrhoea after he had ‘strained himself’ while ‘at drill’ a few days previous.

Being able to see the range of treatments tried is also particularly interesting. Circumcision, bed rest, light diet, urinary antiseptics, anti-gonococcus serum and Salvarsan are all listed in various sheets.

There is also the case of one poor gent who was admitted to hospital on 11 January 1915, suffering from syphilis. The next day his penis was badly swollen and inflamed. This continued until 18 January, when he was operated on to allow discharge to escape. Not particularly pleasant!

- Syphilis case sheet (catalogue reference: MH106/2106)

- Gonorrhoea case sheet (catalogue reference: MH 106/2106)

Hospital stays could be lengthy, and treatment not pleasant. It was the concealment of VD that was punishable, not the contracting of it. All the same, those who underwent treatment in hospital were penalised by hospital stoppages. This meant that any man who was admitted to hospital for reasons not connected to his service was liable to have money from his pay stopped in order to help fund his hospital treatment. For officers this was 2 shillings 6 pence, and for other ranks 7 pence, per day.

Specially qualified officers of the Royal Army Medical Corps and of the civil profession were appointed in centres where treatment could be carried out. Special hospitals fully equipped with all that was necessary were established where soldiers requiring hospital treatment for VD could receive it. Courses of instruction in the treatment of these diseases were arranged, given by expert officers to general medical practitioners, and large numbers of the latter took advantage of them.

Fears regarding overseas troops

Issues of VD appear to have been of great consternation to those sending troops from overseas to help with the war. The risk of VD was not confined to troops serving abroad: roughly half of all cases were originally contracted in the UK itself, by troops on leave or still in training.

The British authorities were exceedingly slow to act, prompting outraged complaints from Dominion governments whose troops were suffering disproportionately: far from the constrictions of being at home and unable to return their on leave, many found prostitutes an appealing and affordable solace. These troops were also better paid than their British counterparts, and with this inability to return home, they had more money to spend on such things.

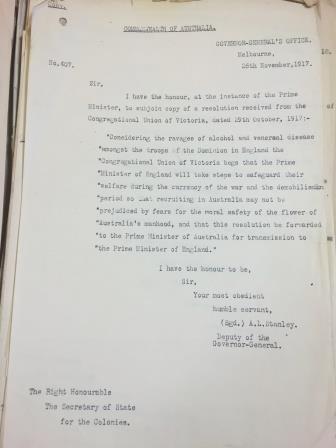

There are a number of letters and telegrams sent from officials expressing distress at the problems with VD among troops already serving, and questioning whether they should send any more men over, if they were likely to become infected. One from Australia reads as follows:

‘Considering the ravages of alcohol and venereal disease amongst the troops of the Dominion in England the Congregational Union of Victoria begs that the Prime Minister of England will take steps to safeguard their welfare during the currency of the war and the demobilisation period so that recruiting in Australia may not be prejudiced by fears for the moral safety of the flower of Australia’s manhood.’

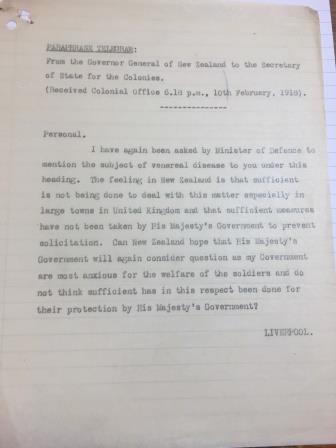

Another similar in tone was received from the Minister of Defence in New Zealand, who was questioning why the British officials had not done more to tackle this issue, especially in large towns, and why more had not been done to prevent solicitation. It concludes with the following lines:

‘Can New Zealand hope that His Majesty’s Government will again consider question as my Government are most anxious for the welfare of the soldiers and do not think sufficient has in this respect been done for their protection by His Majesty’s Government?’

- Letter from the Governor General’s Office, Melbourne, 26 November 1917 (catalogue reference: WO 32/11401)

- From the Governor General of New Zealand, 10 February 1918 (catalogue reference: WO 32/11401)

When British soldiers set off for the trenches in 1914, folded inside each of their Pay Books was a short message. It contained a piece of homely advice, written by Lord Kitchener:

‘In this new experience you may find temptations both in wine and women. You must entirely resist both.’

This was a message which was not always adhered to.

Attempts to combat the problem

Women were excluded from camps, but soldiers visited nearby towns and not only paid for sex but had relationships (which fell outside regulations).

It was also held to be impossible to place London or other centres of population out of bounds for soldiers on leave; a special restriction of this kind upon overseas troops seemed even more objectionable. To make such a distinction would be unfair, and even if such an order were issued in regard to overseas troops its enforcement would be difficult. There were also fears that it would give rise to disciplinary troubles of a serious character.

List of camps in the UK where lectures had been given (catalogue reference: WO 32/11401)

In these circumstances, it was suggested that the best hope of improving that state of matters potentially lay in developing agencies which already existed for educating both the civil and military population and warning them against the dangers of VD; treating persons affected before they communicate the ‘evil’ to others; and the provision of prophylactic measures against infection.

In the army, much was already being done by means of lectures to instruct soldiers in sexual hygiene and to warn them of risks. Up to June 1917, 1648 lectures had been given to 1,270,062 troops by selected lecturers under arrangements made by the National Council For Combating Venereal Disease. The Army Council had further authorised, on the recommendation of their Advisory Committee on the Army Chaplaincy services, the delivery of a series of special addresses on purity at the military centres in the UK. These lectures had been attended by large bodies of troops, and it was hoped to extend their scope in the future.

In addition, opportunities for recreation and games of all kinds for soldiers had been multiplied in order to keep the men healthily engaged.

The National Archives is delighted be partnering with the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) to help commemorate the centenary of the Venereal Diseases Act. Find out more about BASHH on their website and follow them on Twitter at @BASHH_UK

Hello. I have not been able to ascertain a reason for a particular set of circumstances regarding my paternal grandfather and relating to his war service records covering the Great War.

Briefly, he attested in Saskatoon Canada in October 1915, commissioned as an officer (Lieutenant) based on his status as a student of law at U of Saskatchewan). Led troops to Somme September 1916; during artillery attack was buried alive 3 times; resulted in shell shock; interred at the Maudsley as a neurasthenia patient. Discharged November 1916. Sometime between release and early January 1917 contracted VDG and was assigned to a hospital in Boulogne.

I understand there would be treatment of sorts, and he was discharged in Feb 1917. The puzzle is that he was readmitted to hospital for VDG reasons again one year later in early 1918 (service records do not enlighten the reason).

I’ve attempted to ask regular physicians, specialists and even one medical historian about whether there could have been a re-occurrence, or whether he re-afflicted. Knowing him as a grandchild and knowing his virtuous character it is hard to believe the latter.

So, the question is are you aware if a VDG patient, in that era before antibiotics, could re-afflict without any further naughty exploits?

Hi Gregory,

We’re unable to help with research requests on the blog, but if you go to our contact us page: http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

Good luck with your research.

Nell

Were there specific hospitals given over to the treatment of STD’s in the UK? If so which ones were they? I have heard of a VD in Manchester for instance but I do not know which one it was.

During the course of my family history research into my Australian relatives, I ordered the service record of an officer, a married man, and a Military Cross holder. He had contracted Syphilis, and had that word in large bold type overprinted on his Australian military service record, or rather the probable medical section of that record. When writing the family history, I didn’t include that particular detail.