This is my second blog post on Operation Remorse, the secret Second World War operation that earned millions by manipulating currency and smuggling on the Chinese black market. You can read the first post here.

‘Your mission is to establish whatever organisation you may find necessary to secure the extraction of rubber from Japanese-occupied territories.’ (HS 1/288, 15 Sept. 1942)

This was Operation Mickleham’s objective. Walter Fletcher, a wealthy rubber trader, ran the mission between 1942 and 1943. I should say right now that Mickleham failed, utterly. The extent of the failure makes it look like a scam or a blunder, and so people skip over it. But I believe that Mickleham explains the success of Operation Remorse. Remorse relied on Mickleham’s vision, organisation, and insights, helping it succeed where Mickleham failed.

‘Tragi-Comedy: Walter Fletcher’

‘A Tragicomedy: Walter Fletcher’. A mocking internal memo concerning Fletcher’s dealings with the Special Operations Executive. Catalogue Reference: HS 1/192.

Fletcher’s proposal to smuggle rubber from French African colonies had previously been rejected by the Ministry of Economic Warfare and the Special Operations Executive (SOE), but he kept imposing himself. During 1941, he used his company connections to find rubber stockpiles in Indo-China. He suggested blocking Japanese access to these stockpiles and diverting them into Allied hands. His company even bought up some of this rubber in 1942 – and suffered considerable losses. 1

It was bold, but foolish, and SOE were not sympathetic. A mocking memo presented Fletcher’s story as a tragicomedy. The reply came back that it ‘may turn into a crook blackmail play… [Fletcher] is a victim of war and enthusiasm.’ 2 Still, a scheme to ‘extract’ rubber from enemy-occupied territories made sense. The Japanese offensive in the Far East had seized Burma, Malaya and the Dutch East Indies – important rubber-producing areas. The Allies were suffering a critical shortage by mid-1942.

Major L. W. Elliott (‘B/B.303’), appointed by the American Board of Economic Warfare, was busily setting up a rubber-smuggling organisation in Australia. The British thought the scheme ‘fully worth trying (a) on account of the critical scarcity of rubber, (b) from a British prestige point of view’, even though it was ‘unlikely to succeed’. 3 Fletcher went to Washington, and although everyone knew there were problems, discussions were positive and progress was swift. A message exclaimed, ‘At last our Walter has found someone who appreciates him!’ ( HS 1/192, 31 Jul. 1942)

John Walter Albert Newhouse, ‘B/B.301’ – HS 9/1095/4

Newhouse’s file has been opened to the public for the first time by the HS 9 project. He was born in 1916, in Johannesburg. He was a ‘somewhat casual’ Cambridge graduate, a hard worker with leadership qualities. He had worked at Fletcher’s rubber company between 1937 and 1940, but as early as December 1942, Fletcher wanted to do more than smuggle rubber. Maybe his earlier problems had convinced him that Mickleham could not live by rubber alone: ‘It is to throw away the services of invaluable agents to work Mickleham in a rigid rubber waistcoat’.

Fletcher wanted to expand Mickleham into currencies and resources like quinine (for medicine) and wolfram (or tungsten). SOE agreed – in principle. (HS 1/288, 4 Dec. 1942, p. 3; 5 Jan. 1943) Fletcher appointed Newhouse to his ‘Economic Intelligence Department’ in India, to see which resources could be used. Mickleham (originally named ‘Ruby’) was set up under Oliver Lyttelton’s Ministry of Production in February 1943. Over the following months, SOE would prove unable to establish the communications and transport needed to make Mickleham work. Problems like this followed Fletcher everywhere.

Mickleham expanded and recruited talented officers. Bernard Purser (‘B/B.304’), a gruff but careful (and immaculately-groomed) Scottish banker, worked in India alongside Newhouse and Fletcher. B.S. van Deinse (‘B/B.302’), a practical and energetic Dutch civil servant, worked from Ceylon. Kenneth Green (‘B/B.306’) and John Findlay (‘B/B.308’) operated in Burma. Green, once a banker and rubber planter, suited Mickleham, but Fletcher chose Findlay in a rush, and he was often used for other SOE work. 4 Fletcher pushed on into China, strangely confident of success, and the experienced Lieutenant Lionel Ormandy Davis (‘B/B.134’) went too.

‘Fifth Wheel in the Coach’: Operation Mickleham in China

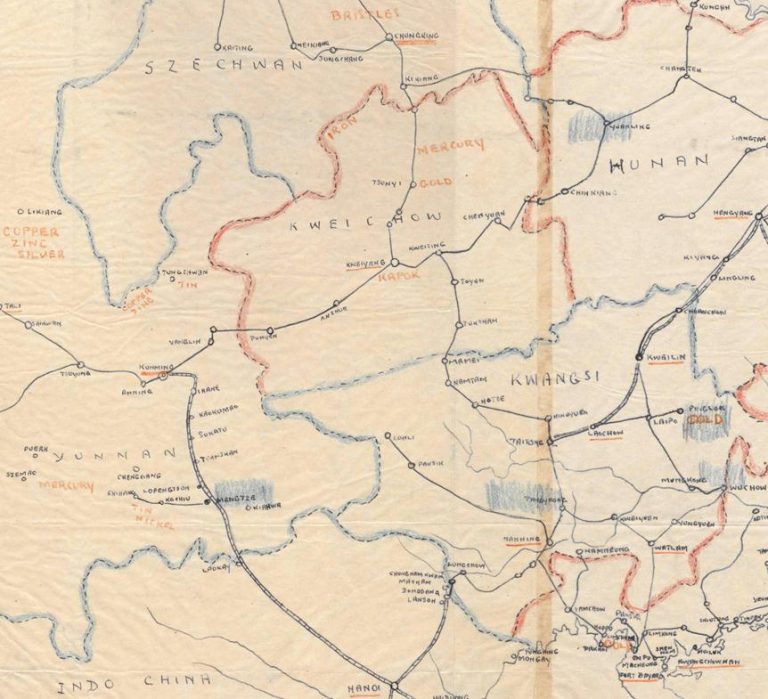

A section of an economic map of China, with resources marked in red. Blue shaded areas indicate Wolfram. This section includes the sites where Operation Remorse would eventually be based: Kunming, Chungking, Mengtsz (or Mengtze), and Kweilin. The Chinese Postal Map system of Romanisation is commonly used in these files, and I use it throughout for convenience. Catalogue Reference: HS 1/293.

Fletcher had claimed Harry Houdini as his ‘patron saint’. (HS 1/288, 7 Jan) He would soon be feeling like him – upside down, in a straitjacket.

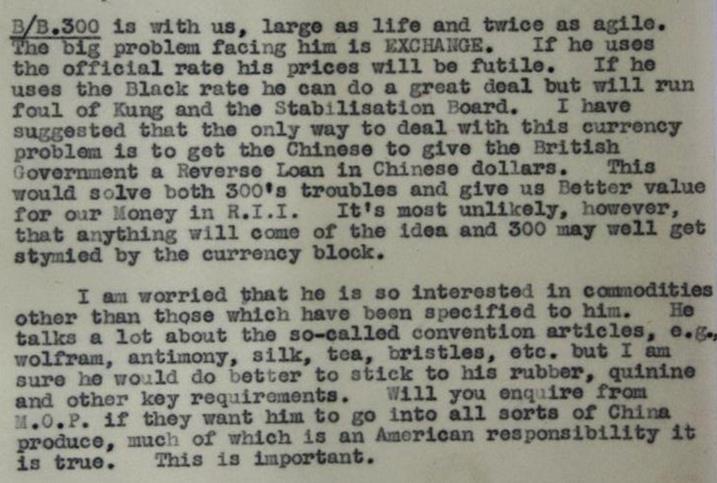

The Chinese smuggling rackets had promised big returns of rubber. Smuggling from Indo-China looked likelier than sea transport. Capable staff joined Davis, like his nephew, Arthur (‘B/B.309’), and Lieutenant G.J.P. Carey (‘B/B.307’), a precise worker with ‘a natural liking for Chinese’. 5 All this meant nothing. High inflation and poor exchange rates meant that Mickleham didn’t have the money to smuggle rubber. Mickleham wasn’t permitted to do anything on the black market, which seemed to be the only way out of the problem. 6 By May 1943, the American Major Elliott had all but given up.

Exchange problems stopped Mickleham from obtaining rubber, and Fletcher’s intention to deal in other goods caused alarm. Catalogue reference: HS 1/289.

That same month, the Treasury finally let Mickleham try the black market. They turned a tidy profit. Encouraged, Fletcher wanted permission to pursue other opportunities, such as silk and tea. This worried SOE, who backpedalled and confined Mickleham to rubber. Fletcher was a risk: ‘they did not believe that they could control him…they would be always discovering new and embarrassing commitments’. (HS 7/259, p. 337) He had made a breakthrough, but by repeatedly ‘straying beyond his mandate’, he had overreached himself. His commercial vision for Mickleham clashed with SOE’s stricter idea of Mickleham as an operation for war materials. The restrictions threatened to make Mickleham ‘the fifth wheel in the coach’ in China – unable to smuggle rubber, but not allowed to do anything else.

Mickleham ‘never produced an ounce’ of rubber, by Fletcher’s own admission. (HS 1/292, 11 Jan. 1945) Still, they had skilled staff, useful contacts and valuable economic intelligence. With Treasury backing for their black market currency work, they stood to greatly benefit the Allies. Grudgingly, SOE allowed Fletcher to return to London in July 1943 and make his case. He wanted black market trading to become Mickleham’s business. The negotiations went on for months, and ended Mickleham for good.

In a future entry, I hope to look at the transition between Operation Mickleham and Operation Remorse, and how the organisation was reshaped into a money-making machine.

Notes:

- 1. Fletcher’s early plans can be studied in HS 9/519/5, HS 1/192, and HS 3/72. ↩

- 2. HS 1/192, ‘AD/W from AD/U’. ‘AD/U’ was William Johnston ‘Tony’ Keswick, who at this time was Deputy Director of Missions for the Far East and the Americas. ↩

- 3. HS 1/288, 29 Jun. 1942. For the first meeting, on 10th April 1942, see HS 1/288, ‘Smuggling of Rubber’ and ‘Note of Interview at the Ministry of Supplies. Mr Bretherton’s Room 10th April’. ↩

- 4. HS 9/513/2. Kenneth Ernest Green’s file, HS 9/616/2, has also been opened to the public by the HS 9 Project. ↩

- 5. HS 1/293, 16 Jun. 1943, 14 Aug. 1943. Carey kept the diary whenever Davis was away, in detail – even mentioning which films he saw. ↩

- 6. Businesses and military organisations could buy 80 Chinese National Dollars (CND) for £1. On the black market, it was 400 CND for £1. Using the official exchange rate wasted money. ↩

[…] Tales from the Special Operations Executive: Operation Remorse, part two […]

[…] Executive during World War Two. The articles, written by Jonathan Cole, were first carried on the blog of the National Archives and are reproduced here with kind […]

Hello Jonathon

What was the relationship between REMORSE and the Military Mission 204 operating out of Chungking?

I am assuming none as by 1943 apparently 204 was not under SOE’s remit any more?