This is my fourth blog post on Operation Remorse, the secret Second World War operation for the Special Operations Executive (SOE) that earned millions for Britain. Read the entire series.

‘May you live in interesting times’ – people call that ‘the Chinese curse’. In 1944, China was certainly an ‘interesting’ place to be. In April, Japanese forces pushed deeper into China than ever before, and by September, the Chinese city of Kweilin was under threat. Panic spread, refugees fled west, and markets fluctuated wildly.

You might not think that these would be ideal conditions for business. But Operation Remorse, Britain’s secret scheme to manipulate currency on the black market in order to fund British organisations in the Far East, came through the crisis wealthier than ever. In this entry, I look at how Remorse got on in China and how its members felt about their surroundings.

Mighty ‘Mouse’: Frank Ming Shin Shu (‘B/B.319’)

Remorse launched a smaller operation, ‘Embryo’, behind the advancing Japanese lines: a ‘trade protection band…to be exploited to our advantage’, employing 500 Chinese guerrillas (HS 1/291, 14 Sept. 1944; HS 1/292, 2 Jan. 1946). Lionel Davis, field commander of Remorse, entrusted the operation to his two nephews – Arthur Davis (‘B/B.309’) and Christopher ‘Micky’ Davis (‘B/B.317’). Having been dumped out of Kweilin, Remorse hedged against further losses by building up currency and commodity reserves. ‘Embryo’ withdrew to Kweiyang as the Japanese pushed onwards.

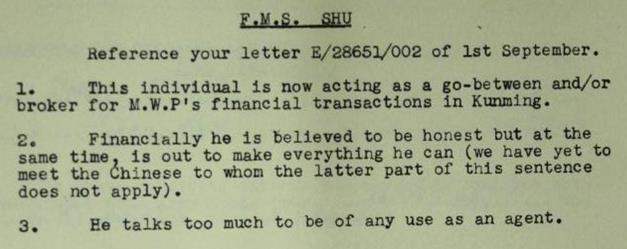

A note on Frank Shu: ‘Financially he is believed to be honest but at the same time, is out to make everything he can (we have yet to meet the Chinese to whom the latter part of this sentence does not apply).’ Catalogue Reference: HS 9/1356/4.

Refugees bolted to Kunming, ‘City of Eternal Spring’. Its population mushroomed tenfold, to a million souls. Kunming’s black market thrived, and Remorse, with its central office in the city at 9 Hsin Chin Kai, stood to gain.[ref] 1. Ryan, R. ‘A Very British Coup’. The Sunday Times [London, England] 22 Jan. 2006. Web. Accessed 3 Apr. 2014.[/ref] Frank Shu, a wealthy Kunming businessman, acted as a broker and contact for Remorse in China, as part of its legitimate business front. Shu was no stranger: he had been a key contact for Operation Mickleham, where he used the codename ‘Mouse’ (HS 1/290, 3 Aug. 1943).

Born in Yantai in 1910, Shu was married with children, and had worked for the British American Tobacco company for 14 years.[ref] 2. Bickers, R. ‘The business of a secret war: Operation ‘Remorse’ and SOE salesmanship in Wartime China’, Intelligence and National Security (2001 16:4), p. 21.[/ref] An Anglophile, fond of Dewar’s Scotch whisky and Fox Terriers, Shu longed for a British Army commission. Walter Fletcher, head of Remorse, was willing to oblige. In an expanding black market, and with memories of the British Secret Intelligence Service’s attempt to poach Shu, Fletcher doubtless wanted to keep a tight grip on this profitable man.

The high life

Not everyone was so keen. A memo replied that ‘he talks too much to be of any use as an agent’, casually adding, ‘Financially he is believed to be honest but at the same time, is out to make everything he can (we have yet to meet the Chinese to whom the latter part of this sentence does not apply)’.[ref] 3. See HS 9/1356/4. Compare this with an earlier note on Shu, which said, ‘be pleasant to him in case we want to use him’ (HS 1/290, 3 Aug. 1943).[/ref] It wasn’t a unique attitude. British attitudes to China and the Chinese were conditioned by decades of stereotypes from exotic fiction – corrupt society, court intrigues, and cowardly soldiers. China was decadent and seductive, and so best avoided by the ‘honest’ British.[ref] 4. Bickers, R. Britain in China: Community, Culture and Colonialism, 1900-1949 (Manchester University Press, 1999), pp. 25-29, 49, 60.[/ref]

Lionel Davis himself claimed that ‘in China everything can be (and has been) developed into a racket.’ (HS 1/289, 30 Sept. 1943) By the end of the war, he hadn’t changed his opinions about ‘the Chinese mind, which is essentially non-military and based on self-interest and greed’ (HS 1/292, 2 Jan. 1946). Even so, when crisis came to Kweilin, he made sure that all the Chinese personnel were evacuated, along with their families.

A note on ‘B/B.319’ Frank Shu’s very profitable currency work, stating that he is ‘keener than ever before’ and showing him planning for the future. Catalogue Reference: HS 1/292.

Meanwhile, Shu proved invaluable. He bought £500,000-worth of ‘semi-blocked’ Rupees (that is, frozen in their accounts) at lower official rates, and then sold them on at the inflated black market prices, with Remorse keeping the profits. When the Treasury wanted trade to go on in other currencies, he dealt with them, too, ‘keener than ever before’ (HS 1/292, 31 Jan. 1945). Davis later claimed that Shu should receive recognition for his skill at handling these ‘vast sums’ (HS 9/1356/4).

Despite occasional periods of crisis, the Remorse team continued to do well out of China, and they played as hard as they worked. Lionel Davis recruited Lorna Tidmarsh, an SOE secretary, on what she called a ‘very boozy evening’ in the West End, which stood her in good stead for Kunming, where parties and hard drinking were common. Edward Wharton-Tigar, a senior Remorse officer, used to sound a whistle at the parties as a ‘last-chance’ signal to the young ladies so they could be driven home at the end of the evening. [ref] 5. Ryan, R. ‘A Very British Coup’. The Sunday Times [London, England] 22 Jan. 2006. Web. Accessed 3 Apr. 2014.[/ref]

Tidmarsh recalled that everyone in the office wore Rolex watches as a ‘perk of the job’. She might not have known at the time that Remorse’s Rolexes had been smuggled from France, under fire: Geoffrey Parker, an SOE surgeon involved in the smuggling, thought that his precious cargo was a batch of special RAF gun sights.[ref] 6. Foot, M.R.D. SOE in France: An account of the work of the British Special Operations Executive in France, 1940-1944 (London: Frank Cass, 2004, p. 328.[/ref] Meanwhile, Wharton-Tigar’s trade in diamonds continued apace – also shipped in from Europe. One report notes the dispatch of £40,000 of diamonds, including one ‘large blue-white stone’ for £2305 (HS 1/291, 2 Dec. 1944). Charles Mackenzie, head of SOE’s mission in the Far East, recalled having as much as £20,000 in diamonds on his desk in one go.[ref] 7. Bailey, R. Forgotten Voices of of the Secret War: a new history of Special operations in the Second World War (London: Ebury, 2008), p. 278.[/ref]

‘Masterkey’

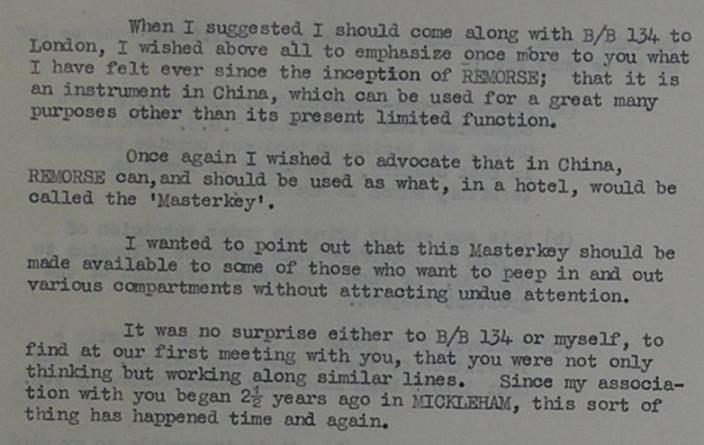

Despite this, not everyone was satisfied. In January 1945, B S van Deinse, Dutch civil servant and advisor to the operation, wrote a lengthy memo urging the British to take fullest advantage of the ‘chaotic financial situation’ – instead of limiting itself to racking up funds, Remorse could become a true ‘fifth column’ organisation in the heart of China, since it was ‘more suitable for all purposes in China than any other organisation which has not Remorse’s nature’. In its more ambitious passages, the memo suggested establishing intelligence posts all over China – ‘wherever the Americans are likely to land’ – even in Japan, if possible. Finance and commerce, Remorse’s speciality, was the key to this plan: ‘in China, Remorse can and should be used as what, in a hotel, would be called the ‘Masterkey.” (HS 1/292, 25 Jan. 1945)

B.S. van Deinse’s bold memo, describing Remorse’s future potential as a ‘Masterkey’ in China. Catalogue Reference: HS 1/292.

The memo is so bold, not just because of van Deinse’s character, but also due to the conviction that the operation was ‘a weapon based on the knowledge and understanding of the Chinese mind’ (HS 1/292, 2 Jan. 1946): van Deinse was sure that Walter Fletcher and Lionel Davis in particular had the advantage of an ‘enormous understanding of the Chinese mentality’, ‘more…in two years than many Europeans in China after 25 years’. Bribery was therefore seen as a means to an end in a country with ‘many people who are ready to sell their soul and country to the highest bidder for money or goods or power’, particularly in such ‘interesting’ times. (HS 1/292, 25 Jan. 1945)

With the swagger that comes from success, Operation Remorse was looking to transform itself into the most powerful operational force for Britain in China. In a future entry, I intend to look at Remorse’s final months in China, expanding its reach into an increasing number of activities as the war drew to its end.

[…] Executive in World War Two. The articles, written by Jonathan Cole, were first carried on the blog of the National Archives and are reproduced here with kind […]