This week marks BBC’s Civilisations Festival, where museums, galleries, libraries and archives across the country are running events and sharing ideas that spark debate and foster exploration about what is meant by the term ‘civilisation’.

‘Civilisation is not something to be kept in a museum or buried in a library. Civilisation is in the making and our task is to keep it perpetually alive.’ (Catalogue reference: BW 2/505)

This bold claim was made by Léon Marchal, secretary-general of the Council of Europe, in a 1954 speech to mark the release of the book ‘The European Inheritance’. While I agree with him that civilisation is constantly in the making, that society is always striving to better itself, I wholeheartedly disagree with his sentiment that civilisation is ‘buried’ if it is kept in a museum or library – or in an archive, of course. In fact, quite the opposite is true.

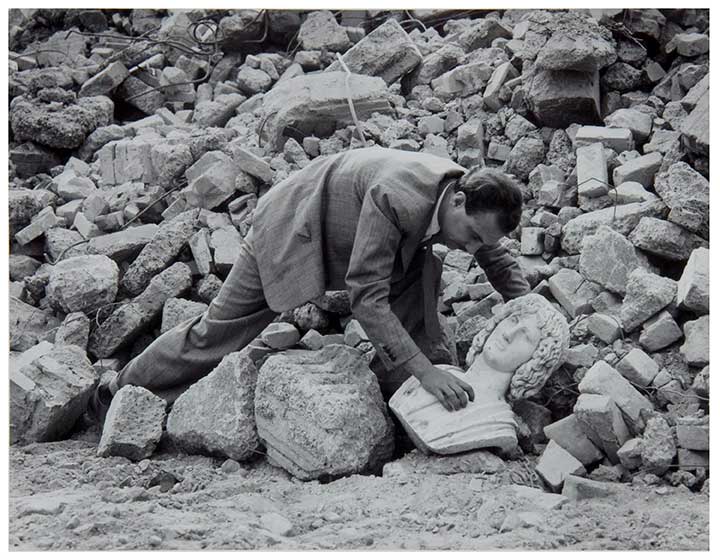

Archaeological find, 1949-1950 (WORK 25/196)

It is vitally important that the records of our civilisation are kept and – even more vitally – used: to inform, to inspire, to educate. Archives are civilisation. Records in strong-rooms the length and breadth of this country and beyond tell stories that testify to the development and progress of our civilisation. Stories of people, of businesses, of government; stories of bravery, oppression, of success, of failure. These stories are important.

Civilisation in the archives

I see civilisation as humanity’s forward march of progress. Of course, there are records that more clearly demonstrate such progress – Magna Carta, or the records of the women’s suffrage movement, for example. These are clear examples of records that practically shout civilisation at us; of society progressing and advancing, bettering itself.

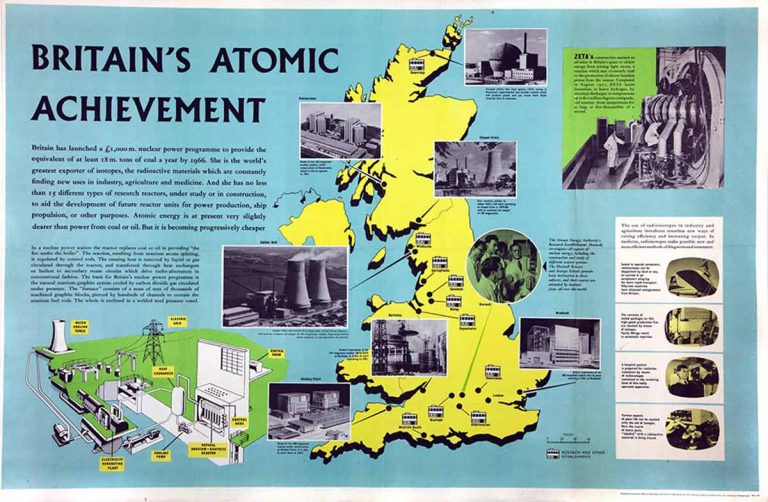

However, all records can be poised to tell a story of how we got to where we are today. Take, for example the lecture given by Sir John Cockcroft, as part of the Ballard Mathews Lectures at Bangor University in March 1959. His second lecture, entitled ‘The Influence of Nuclear Physics on the Development of our Civilisation’, explored his involvement in the field of nuclear energy and the development in the 1940s and 1950s of ‘nuclear electricity’ as an alternative to coal for the country’s energy needs.

‘If we look at the future of the world’s energy needs we can see that without nuclear energy the long term prospects for continuing our present rate of improvement of the world’s standard of living would be black.’ Sir John Cockcroft, March 1959 (Catalogue reference: AB 27/21).

Britain’s Atomic Achievement poster, 1950s (EXT 1/123 pt 2)

Reading that statement with our 21st century perspective on nuclear energy it is easy to dismiss his statement as misguided. However, take ‘nuclear energy’ out of that statement, and replace it with ‘renewable energy’, and that statement could have been written today, in 2018. His lecture considers exploring and developing new scientific means to advance our society – or, rather, civilisation – and so reinforces Léon Marchal’s statement that civilisation is constantly in the making and also my own that archives are essential in understanding the development and progress of that civilisation.

Stories to inspire

‘How?’ you may ask. How can we see civilisation in these records? Put simply, records are the evidence of our progress. They contain the stories that enable us to understand, articulate, and learn from that progress.

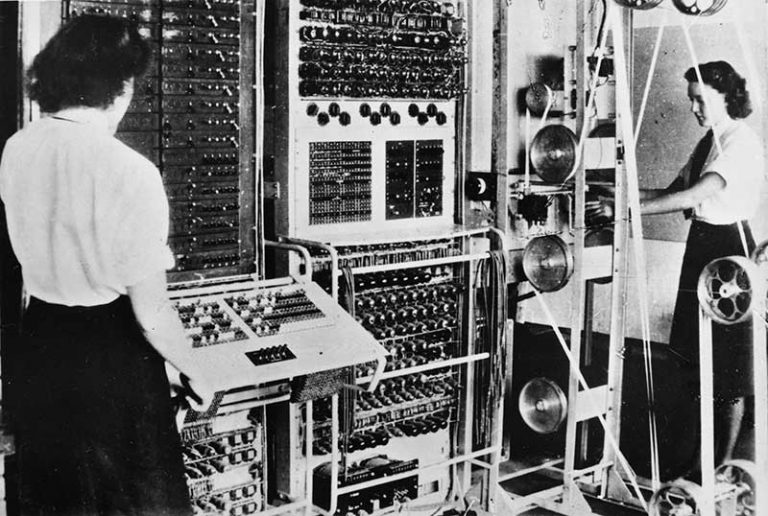

We, as archivists, are in the perfect position to bring these stories to life by opening up our collections to the public – to inspire, to celebrate, to spark debate, to encourage learning. We are able to bring these stories out and connect with our communities by leveraging another great example of civilisation’s progress – digital technology. We have the ability to bring collections into our communities in new and exciting ways. The advent of digitisation in the archival world was a watershed moment in our outreach capabilities.

Digital technology: making it easier for archives to accessed (catalogue reference; FO850-234).

Archive collections suddenly became tangible to many more and different audiences. They suddenly had meaning. People who, before, might not have even known what an archive was, or that the records they contain could mean anything to them, were suddenly able to see history on their own computer screens. They were brought face to face with a history – a story – that meant something to them; that could inspire, validate, teach or, quite simply, intrigue.

Archives are essential to our cultural heritage. It is important that we open up our collections to tell the many wonderful stories that exist inside those boxes, and also to engage our communities with collections in ways that enable new stories and narratives to emerge; stories that will ultimately ensure our civilisation is kept perpetually alive.

The view of civilisation as ‘humanity’s forward march of progress’ is naïve in the extreme and profoundly whiggish. It also rather begs the question, whose progress? One person’s progress is another’s regress.