Madame Hella Vuolijoki (catalogue reference: KV 2/1393)

In 1920 a scandal involving one of Britain’s most senior and celebrated generals from the First World War, a leading naval officer and a communist Finnish actress rocked the British establishment. Documents held here at The National Archives reveal the true extent of this long-forgotten spy story.

The tale started when the Finnish authorities raided the house of Madame Hella Vuolijoki, a leading figure in Finnish society suspected of supplying intelligence to the newly formed Soviet authorities in Russia. Vuolijoki was an interesting character who had previously come to the attention of MI5. Their agent reported that she was:

‘Very well known in Helsingfors, is clever, far seeing, extremely energetic. Keeps salon. Is greatest champion of proletariat and Soviet Russia. Employs all her woman’s wit and energy in trying to catch and impose her views on prominent foreign journalists and diplomats who frequent her salon, and listen to her views on the great questions of the day.’ (KV 2/1393)

She was on the MI5 blacklist of individuals barred from entering the UK and was, at various times, believed to be operating as a spy for the Germans, the Soviets and the Japanese.

Home Office blacklist (catalogue reference: KV 2/1393)

General Sir Hubert Gough (Image courtesy of (c) IWM Q 35825D)

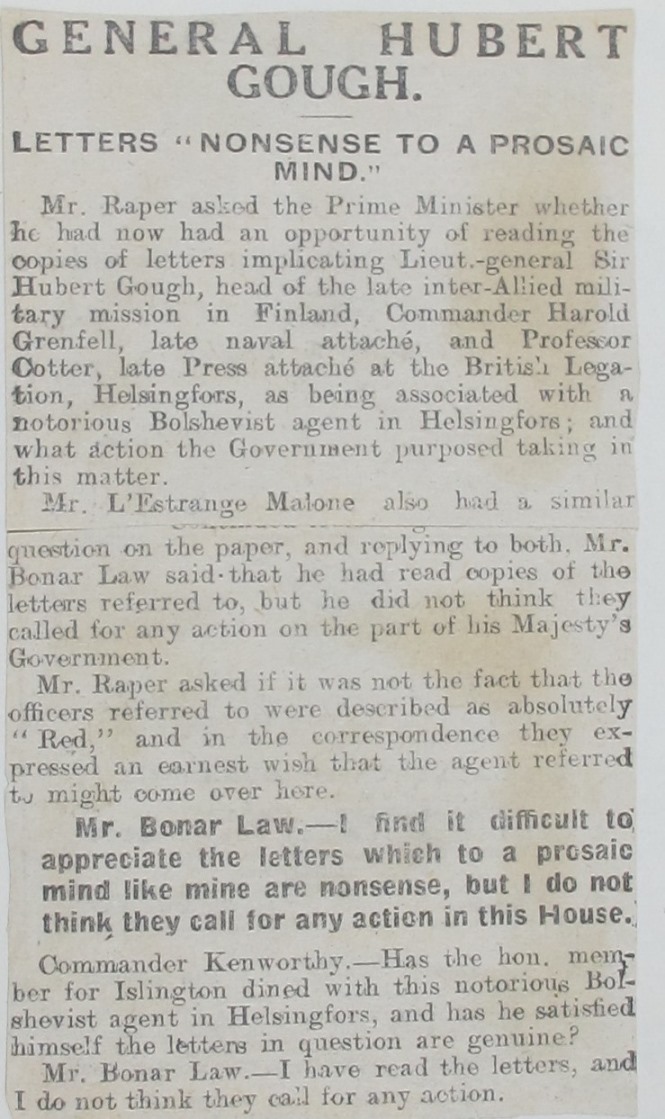

When the Finnish police raided the house they found incriminating correspondence from a number of leading figures including the renowned British general, Sir Hubert Gough. Gough had been one of the youngest Army Commanders in the First World War and had led troops at many of the major engagements including the Somme and Passchendaele.

His reputation had been badly affected by defeat in the German offensive of March 1918, but he had been rehabilitated and appointed Chief of the Allied Military Mission in the Baltic. In this role he was supposed to be helping the White Russians fighting the Bolsheviks. Gough had already caused eyebrows to be raised in London when he lobbied hard for Vuolijoki to be allowed to travel to Britain, declaring that she is not ‘red’ but a very mild ‘pink’ (KV 2/1394). The recovery of letters from the house of this suspected Soviet agent appeared to raise serious doubts about Gough’s actions in the Baltic.

Gough was not the only one whose correspondence was found in Vuolijoki’s house. Captain Harold Grenfell, formerly British Naval Attaché to Russia, was heavily implicated by his letters to Vuolijoki. Earlier in 1920 he had written to her about British political leaders, declaring that ‘their blindfear and hatred of any form of Socialism or of real Democracy seems to have unbalanced their minds’. Despite this he went on that ‘I have simply been astonished to find here [in London] how Red sentiments are making way in the most unexpected quarters’. Indeed as Grenfell put it some of the younger generation he encountered were ‘almost as red as myself’ (FO 800/153).

Perhaps unsurprisingly the story soon found its way into the press in Britain and was quickly raised in Parliament. Alfred Raper MP exaggerated slightly when claiming that the documents showed that senior military and naval officers were ‘known to be plotting for the introduction of a Bolshevist regime in this country’ (HC Deb 01 July 1920 vol 131 c638). He went on to press the government to know what action they would take. Following considerable prevarication the Prime Minister, Andrew Bonar Law, did his best to play down the issue. He stated that ‘I found it difficult to have patience to read the letters, which, to a prosaic mind like mine, seemed nonsense: but I do not think they call for any action’ (HC Deb 13 July 1920 vol 131 cc2145-6). Such limited remarks did little to reassure those clamouring for action, or to restore the reputations of the individuals involved.

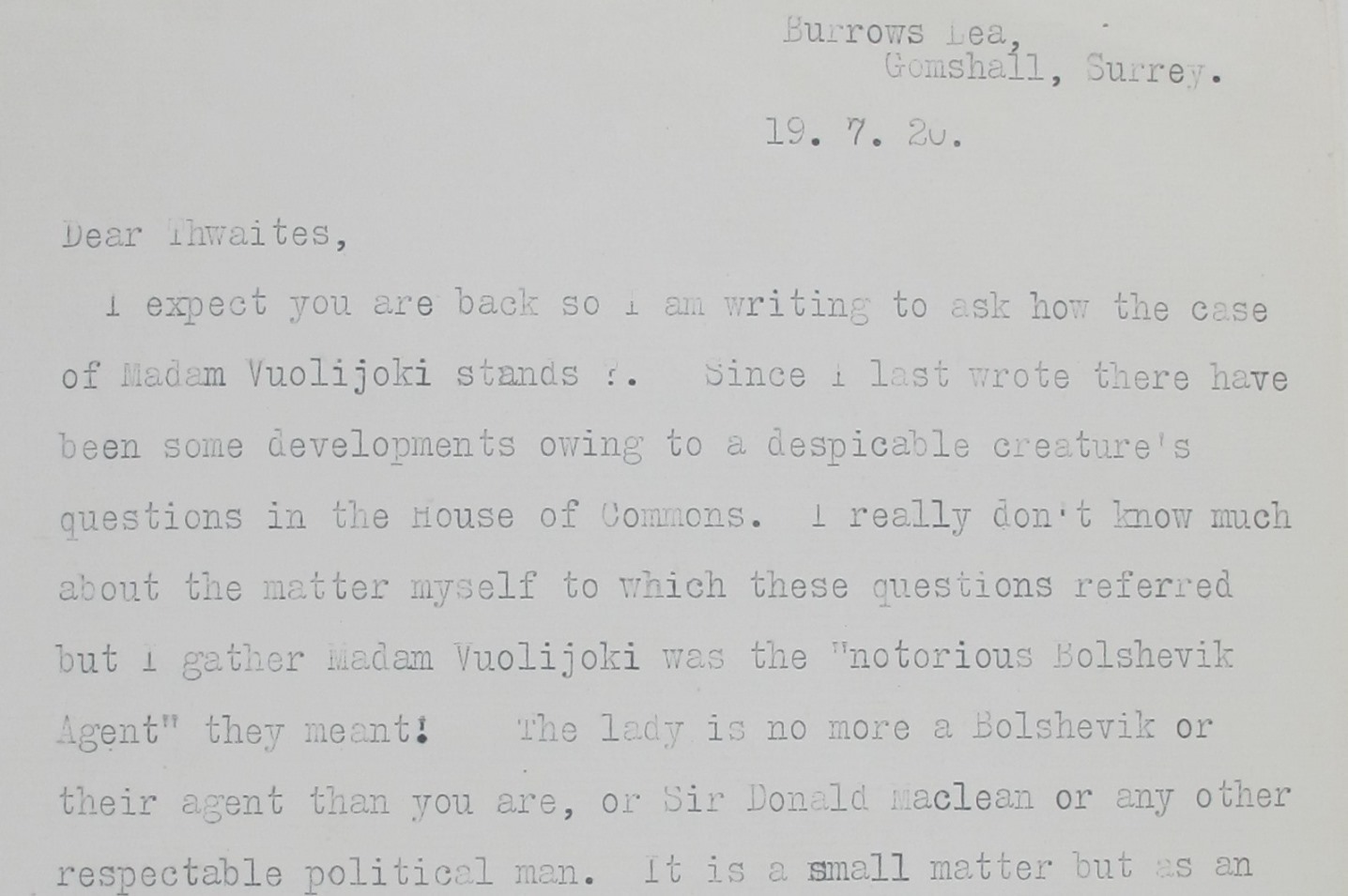

Following the issue arising in Parliament Gough went on the offensive. He wrote an angry letter to William Thwaites, Director of Military Intelligence, attacking Raper as a ‘despicable creature’ and claiming it to be a personal attack on him. Remarkably he stood by Vuolijoki stating that ‘the lady is no more a Bolshevik or their agent that you are, or Sir Donald Maclean, or any other respectable man’. He even continued to press for her to be allowed into Britain. Thwaites was far from convinced, replying that ‘unfortunately I know more about the lady than you may suppose.’ (KV 2/1394)

Gough’s letter to William Thwaites, July 1920 (catalogue reference: KV 2/1394)

With hindsight it is obvious that Gough had, at best, seriously misjudged his friends in Finland. Vuolijoki’s MI5 file makes it clear that she was very close with senior Soviet figures, and making considerable money from her connections with Soviet intelligence. As late as 1946 she was meeting leading communists including Stalin, by whom she was ‘favourably impressed’ (KV 2/1394). Grenfell was also an ardent communist, who had already come to MI5’s attention by 1920, but would go on to actively promote the establishment of a communist government in Britain. He would remain close to Vuolijoki, and MI5 believed that they were in a long-term relationship through much of the later 1920s (KV 2/506).

Although now entirely forgotten this little episode almost certainly put the final nail in the coffin of Sir Hubert Gough’s once illustrious military career. Beyond this it shines a light on the rapidly changing world of post-First World War Europe, and the new uncertainties created by the rise of radical politics and ideologies.

Blogs by the same author

Garbo: the story behind Britain’s greatest Double Cross agent

It’s ‘Finnish’, not ‘Finish’.

[…] techadmin on October 17, 2016 Spies in the Baltic: the unknown scandal2016-10-17T08:15:10+00:00 – Journals & Publications – No […]

This scandal underlines the poor judgment of Hubert Gough and shows him to have been a liability. It confirms Gough’s reputation for being a complete ‘plonker’. His support of Gough and his promotion of him way beyond his capabilities in 1915-16 also shows a singular lack of judgment on Douglas Haig’s part.

Harold Grenfell was far from being an ‘ardent communist’; he was one of the many who hailed the triumph of Bolshevism as a victory for progressive forces, and was active in supporting pro-Bolshevik causes, such as the hands Off Russia movement, but there is no evidence of his ever having joined the British Communist Party. He was a supporter of the Independent Labour Party, and even hoped to fight a constituency for the party, but, judging by his letter, he was soon disillusioned with politics. Wuolijoki was a good deal smarter, a woman who seemed able to charm a very large number of men in order to make her own way in the world – Grenfell was at some stage involved in his business ventures, though more as a useful channel than as an active participant. A frustrated middle-aged idealist – certainly not a hard-bitten communist!