Why were Indian servicemen fighting at The Somme? What happened to the men whose physical and mental health was irrevocably altered by their experience on the battlefield? What aspects of women’s work on the Home Front did the British Government not want the public to see?

The Education team teamed up with 90 local secondary school students to answer these questions in our special schools event held on Monday 27 June to commemorate the centenary of the Battle of The Somme. Working with St Mark’s Catholic School, Lampton School and Isleworth and Syon School, we delved deep into our collection to discover more about the hidden histories of The Somme Offensive.

Monday 27 June 2016 saw 90 students visit The National Archives to explore original documents relating to the Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme features in many schools’ schemes of learning on the First World War. In fact, this episode of history is rather well-traversed in the classrooms of Britain. A quick browse through a textbook or a search through the teachers’ resources on the Times Educational Supplement website reveals an array of student enquiries on the topic of The Somme: ‘Haig: Butcher of the Somme?’, ‘Lions led by donkeys?’, ‘Was the Battle of the Somme necessary?’ and so on.

So, what can a special event at The National Archives offer schools that isn’t already studied effectively in their own classrooms?

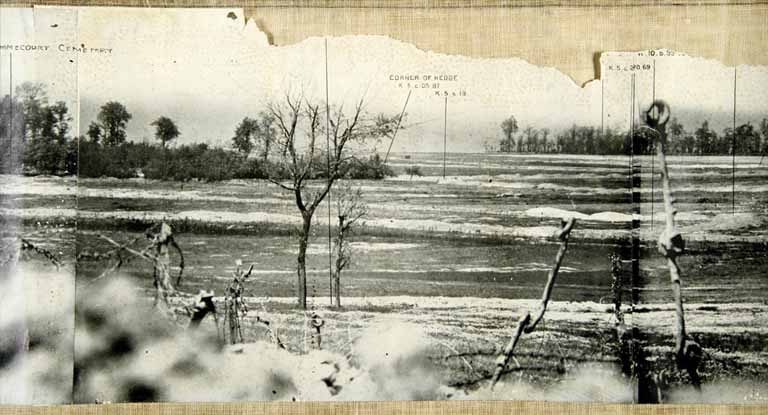

Third army panorama Gommecourt 20 May 1916 (cat ref: WO316-38 (5))

Our resident historian Andrew Regis, played by Andrew Ashmore

On arrival, students were immediately tasked by our resident historian Andrew Regis to conduct archival research on the lesser-known aspects of The Somme Offensive. Working closely with education officers and researchers from our Advice and Records Knowledge department, students quickly discovered that hidden between the cracks in popular memory exist many untold stories.

For example, students from Isleworth and Syon School were given the chance to explore the contribution of soldiers who came from all over the Commonwealth to fight at The Somme. Students read and analysed moving stories from records of soldiers from Australia, Canada and India. Their positions during particular offensives were plotted on trench maps using map references from War Diaries, with this work culminating in a display which consolidated the students’ learning.

For many students, the Somme Offensive started and ended in the trenches. However, St Mark’s students’ examination of series PIN 26 revealed that the long-term well-being of soldiers was significantly altered by injuries sustained in battle. This included soldiers like Ernest Silverman whose amputation caused many health problems throughout his life, at times impeding his ability to work as a hairdresser. MUN 7/331 reveals the Government’s response to the demand for high-quality technology to support the civilian lives of returning servicemen, including designs for adapted tools which would allow amputees to work as carpenters or metalworkers. Here, students’ examination of the records revealed that for survivors of The Somme, the end of the battle signified the beginning of a life shaped by their experience on the battlefield.

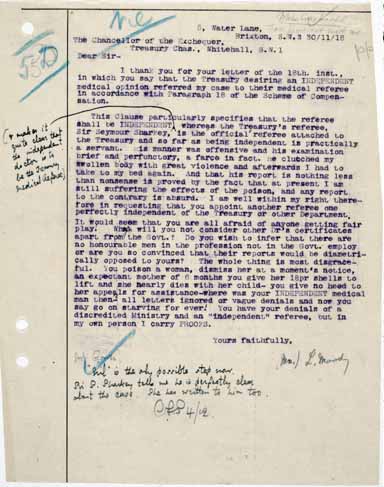

Furthermore, comparatively little recognition is given to the women who supported the soldiers that fought on the front. The documents stored in the munitions and treasury files gave Lampton students an insight into the experiences of some of the women who served on the Home Front. These files revealed a darker side to women’s war work. T 1/12200/36707 , for example, documents the compensation case of Lily Moody, who suffered TNT poisoning during her time at Woolwich Arsenal explosives factory – consequently becoming very ill and losing her unborn child. Lampton students examined Moody’s powerful letters and the consequent dismissal of her case to reveal the attitude of the Government towards its munitions workers.

Letter from munitions worker Lily Moody addressed to the Chancellor of the Exchequer, examined by students at Lampton School (cat ref: T1 12200/36707)

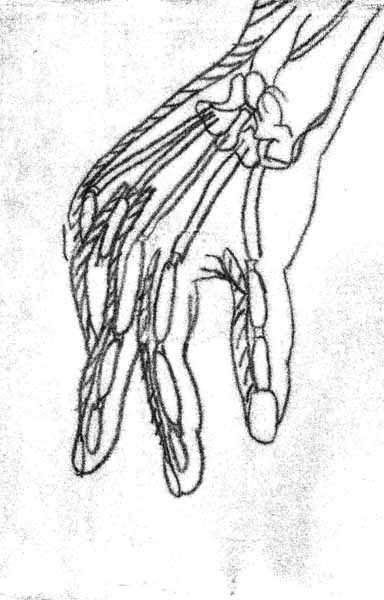

In the afternoon, the students used creative means to develop their learning from the morning. St Mark’s worked with illustrator Merlin Evans to create artwork using traditional mono-printing techniques. Their prints were inspired by the designs for artificial limbs and adapted carpentry tools found in MUN 7/331 and MUN 7/285.

Design for a prosthetic hand created by a student at St Mark’s Catholic School

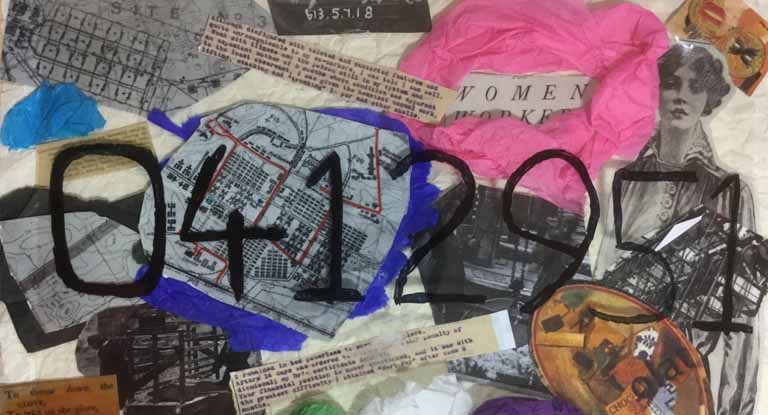

Lampton School worked with artist Poppy Szaybo to create collages inspired by some of the dangers and challenges women faced working in munition factories, such as TNT poisoning, strikes and explosions. These collages utilised facsimiles of documents and photographs found in MUN 4/1720, T 1/12200/36707 and MUN 5/297.

Isleworth and Syon students worked with Sarah Hutton to compose Tanka poems about a soldier’s experience in the trenches. Tankas are a form of Japanese poetry that uses five lines to convey strong emotions. The students’ brief but extremely emotive Tankas were the counterpoint to the concise language of the official war diary accounts they had encountered in the morning.

Many thanks to our fantastic students who did a wonderful job as archival researchers. You successfully used the documents held at The National Archives to challenge and extend common understandings of The Somme Offensive, utilising some very high-level historical skills throughout. Thanks too to all those in the organisation who supported this event – it was a team effort!

If you’re a school that would like to visit The National Archives to learn more about the First World War, feel free to book one of our free workshops or browse our online collection of soldiers’ letters from the front.

This blog has been collaboratively produced by Onsite Education team members Annie Davis, Ela Kaczmarska, Rachel Hillman and Rowena Hillel.

A collage created by a student at Lampton school

First World War researcher James Fleming instructs Isleworth and Syon students on the reading of trench maps.

The attitude of the Government (really that means the Treasury) in their attitude to munition workers (including men as well in the factories) is no different to their attitude to workers generally which lasted for at least the next 50 years, whether you are working in a naval dockyard or a munitions factory. If the injuries were not to be attributable to their official duties then the person or their representatives were unlikely to be compensated. Treasury in those days was very much different from today, a few men at the top who were career civil servants working normally from 9 am to 4 pm or 10am to 5 pm and would not expect to be told what to do in these types of cases, Treasury would expect to tell departments what to do and not the other way around.