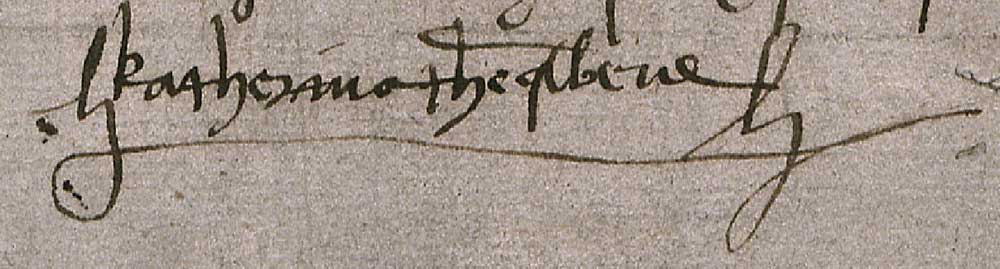

The signature of Katherine of Aragon on a letter to Thomas Wolsey written in 1513 (catalogue reference: SP 1/5, no.219)

In this evening’s episode of BBC One’s Six Wives with Lucy Worsley, Lucy gets exclusive access to film the love letters of Henry VIII to Anne Boleyn which are now housed in the Vatican Library. How they got there nobody knows, but there they are in their glory, depicting the all-encompassing love of the King for his ‘awne sweth hart’.

The Vatican Library, through its digitisation programme, is making many of its unique and beautiful manuscripts available to a worldwide audience. We can all read through Henry’s letters as they were originally penned – but you need to know the numeric archival reference to find them (Bibl. Vat. lat. 3731 pt A) as there are no online descriptions to search.

Many relevant documents remain hidden from historians in the Vatican and elsewhere often because their online archival catalogues provide insufficient detail to identify rich sources for British early modern history. We can turn to the efforts of my predecessors at the Public Record Office in an attempt to overcome this though.

In the 19th century, the British government demonstrated its commitment to the study of early modern history by employing a series of researchers to work in major European archives, reading a wide range of documents and transcribing those which cast light on the personalities, events, networks and conflicts that made up the political history of all parts of the British Isles during the 16th and 17th centuries.

The result of some of this activity was the publication of Calendars (that is, chronologically arranged summaries) of the documents found in Spain, Vienna, Brussels, Venice and Milan. Where they exist, these publications have played a crucial part in the writing of political histories on the reign of Henry VIII and those of his children. For Rome, though, the Calendars only cover the period before the Protestant Reformation and 1558-1578. The Spanish Calendar ends in 1603 and that for Venice in 1675. For France and Sweden, no Calendars were published at all.

Many researchers are unaware that The National Archives still holds the 19th century transcripts which were used to create the Calendars as well as many which have never been translated, summarised or published. They are in various record series in PRO 31 and, whereas the Calendars contain translated summaries, the transcripts are often complete copies in their original language. They were heavily scrutinised by historians when they were first sent back to the Public Record Office but now, perhaps as international travel for scholars has become easier, they are little used. Their obscurity is not helped by abbreviated catalogue descriptions (such as PRO 31/9/3: Stevenson: Arch. Secr. Miscellanea, 1516-1612) which are not designed for modern search engines.

The transcripts represent a body of scholarship in their own right as a curated selection of documents, gathered over many decades, sometimes from obscure sources. Obviously, nothing is better than reading documents in their original state, but for academics with easier access to The National Archives than to Rome or Paris this collection offers a tailored finding aid into the resources available across mainland Europe.

As an example of the contents, the Spanish Calendar gives us insight into the early relationship between Henry VIII and his first wife, Katherine of Aragon, with a letter written by the Queen on 27 May 1510 from ‘Granuche’ (Greenwich) to her father, Ferdinand of Aragon. In it she tells him the sad news that her first-born child, a daughter, has died.

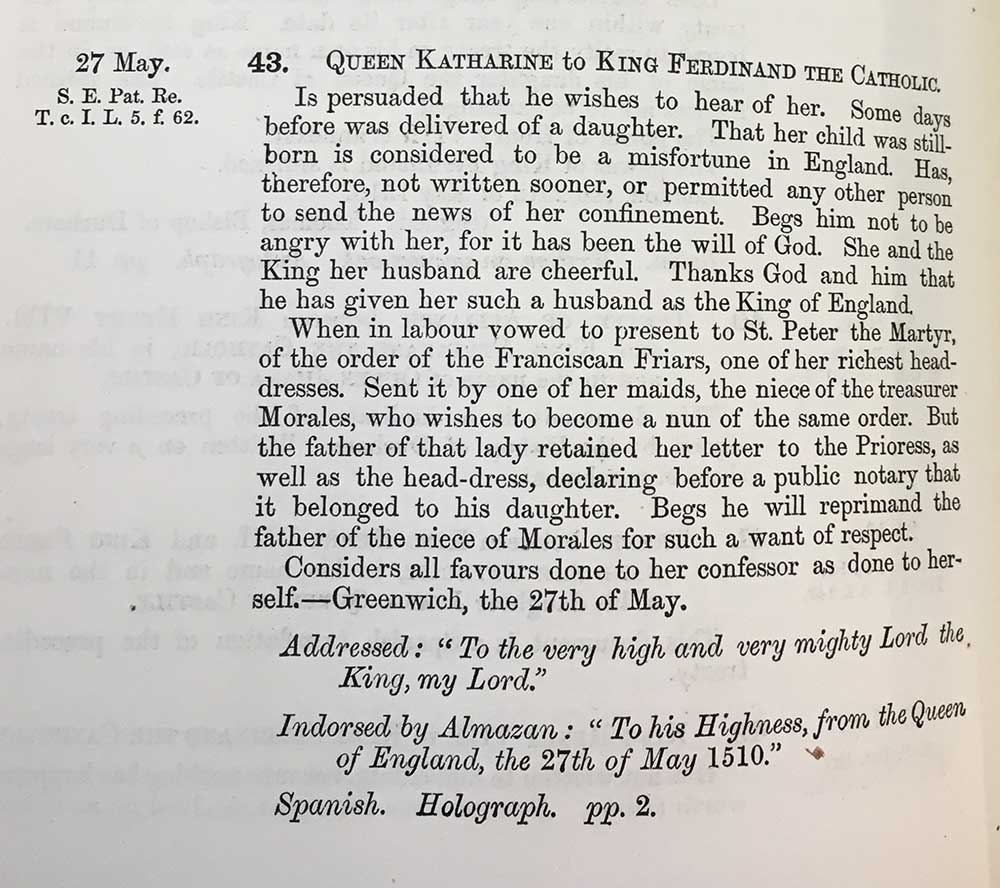

The letter is also summarised in Letters and Papers of Henry VIII, reporting that Katherine:

Was delivered of a daughter, still-born, an event which in England is considered unlucky, and therefore she has not written sooner. She and her husband cheerful. Thanks God for such a husband.

Her affection for Henry VIII and optimism in the face of the loss of their first child is particularly poignant as we know how her marriage was to unravel 20 years later.

Extract from Calendar of State Papers, Spain, volume 2, page 38

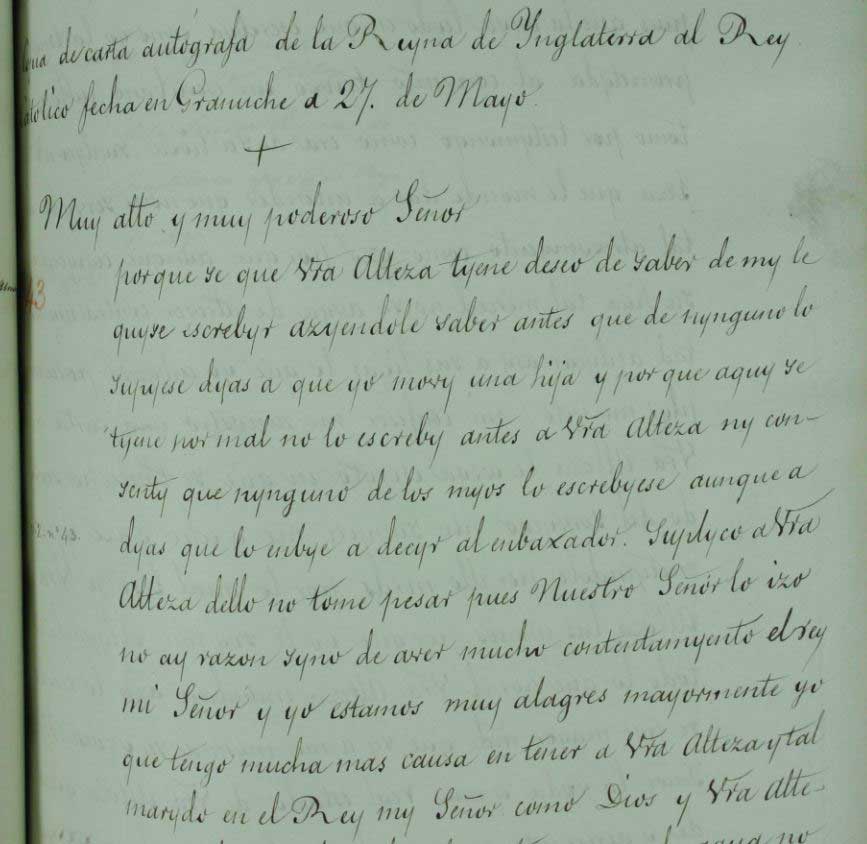

Turning to the full transcript in the original Spanish in PRO 31/11/5 we see that the letter is longer than its summary and, although written in a more modern hand, it retains the fluidity of 16th century spelling and lacks the trammels of excessive punctuation. It is clear that the Calendar summary is only one interpretation of the text.

Extract from transcript of letter written by Katherine of Aragon to her father, 27 May 1510 (catalogue reference: PRO 31/11/5, f.119)

The original letter, which has been digitised and can be found in the Patronato Real > Capitulaciones con Inglaterra series of records in the Archives in Simancas, provides further material clues as to the state of mind of the writer and the accuracy of the transcription, but the records in PRO 31 open a door for researchers into the riches awaiting them across the Channel.