The final episode of Lucy Worsley’s Six Wives focuses on the fate of Henry VIII’s last three consorts, so we are taking a closer look at some of the documents held at The National Archives relating to the complicated nature of Katherine Howard’s sexual relationships and the reaction of the court to these revelations.

Katherine Howard became queen in 1540 after Henry VIII’s unwillingness to remain married to Anne of Cleves saw their frustrated union end in divorce. Katherine was in her late teens by 1540, yet already had a complicated sexual past for a royal consort. She was sexually abused by one of her tutors, Henry Manox, and was later pursued by Francis Dereham, a kinsman of the duke of Norfolk. Katherine received Dereham and another man into her bedchamber in 1538, after which Dereham described Katherine as his wife.[ref]1. Katherine Howard’s early years have been extensively covered in: L. Baldwin Smith, ‘A Tudor Tragedy: The life and times of Catherine Howard’ (London, 1961).[/ref] Manox, Katherine’s original tormentor, learned of the relationship and informed Katherine’s grandmother, after which Dereham swiftly left for service in Ireland. Katherine did not, however, disclose her sexual past to the king before their marriage. This fact shaped the subsequent events.

Henry’s roving eye had fallen upon Katherine, and after a brief courtship she settled into her role as queen. Katherine enjoyed the trappings of courtly life, but her troubled past soon came back to haunt her. Firstly, Dereham returned from Ireland and demanded a position at court, letting it be known rather flagrantly that the queen would favour him. Soon after, another courtier, Thomas Culpepper, began to pursue the queen through Katherine’s lady-in-waiting, Lady Jane Rochford. How receptive the queen was to these advances was initially ambiguous.

Lady Rochford, widow of George Boleyn, brother of Henry’s second queen (whose fate was outlined in last week’s blog), helped to facilitate Katherine’s secret meetings with Thomas Culpepper, which were to eventually contribute towards her demise. These encounters began in early 1541, and once the cat was out of the bag, various witnesses came to the fore, drawing attention to the nature of their illicit liaisons.

This includes an occasion when Henry and Katherine were staying in the Bishop’s Palace in Lincoln, on their conciliatory royal progress following the northern rebellions. Lady Rochford gave testimony in 1541, which is recorded in the State Papers, concerning what she knew about the situation. She testified that while at Lincoln, late one night, she and the queen were at the back door of the Bishop’s Palace waiting for Culpepper when a member of the night watch came with a light and locked the door. Shortly after this, Culpepper had come into her chamber and Lady Rochford stated that he and his man had picked the lock. Lady Rochford gave her opinion that she thought that Culpepper ‘knew the quene carnally’.[ref]2. Catalogue reference: SP 1/167, f. 143 (Stamp folio number)[/ref] However, the extent to which this was a complicit relationship is disputed.

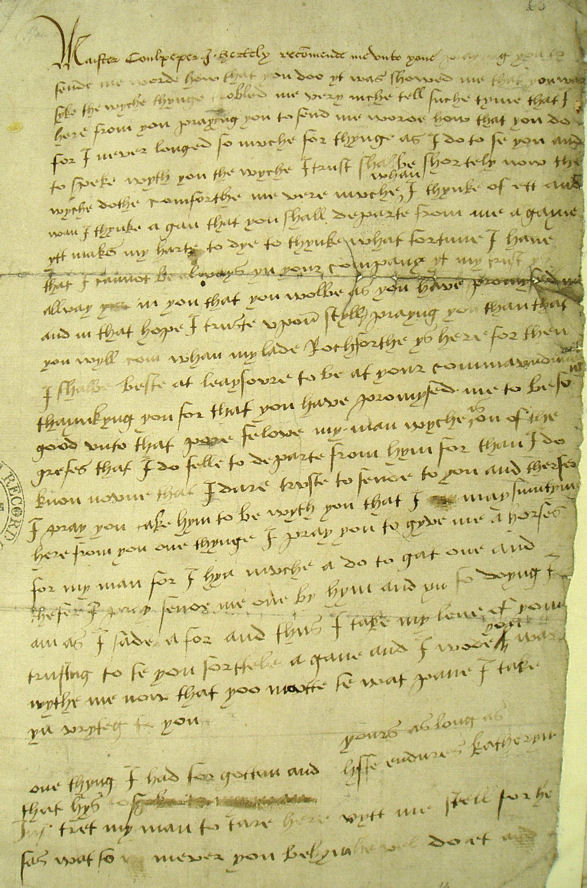

Katherine Howard to Thomas Culpepper (SP 1/167, f. 13)

The National Archives holds the only surviving letter written by Katherine Howard, which she sent to Culpepper. This is undated but was despatched during the progress, perhaps from Liddington (Rutland) or Lincoln, sometime in August 1541. It closes with ‘Yours as long as lyffe endures’, which has often been perceived as evidence of an affair between the two.

Interpreted in another way, the language might suggest that Katherine’s life is dependent upon a secret that Culpepper is keeping for her, and which she urgently wishes to speak with him about, as suggested by the tone of the letter: ‘for I never longed so muche for [a] thyng as I do to se[e] you and to speke wyth you, the wyche I trust shalbe shortely now’.[ref]3. Catalogue reference: SP 1/167, f. 13 (Stamp folio number). For more on the relationship between Katherine Howard and Thomas Culpepper, see: R. Warnicke, ‘Katherine [Katherine Howard] (1518×24–1542)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online edn, Jan 2008 [accessed 19 Dec 2016]; R. Warnicke, ‘Queenship: Politics and Gender in Tudor England’ History Compass, 4 (2006), 209.[/ref] Perhaps Culpepper had knowledge of the queen’s sexual past and was holding the information to ransom, in return for particular privileges.

The court had begun its journey back toward London when details of Katherine’s alleged activities were brought to Archbishop Cranmer’s attention. After Cranmer informed Henry, who was stunned, an investigation was launched and Katherine was arrested, along with Lady Rochford, Dereham, and Culpepper. Cranmer was then tasked with interviewing Katherine to understand the extent of the allegations against her, but unlike the dramatic events of Anne Boleyn’s fall, Katherine quickly admitted her guilt.

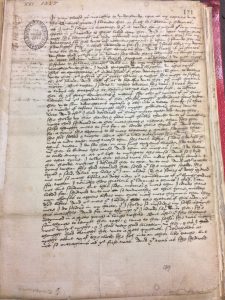

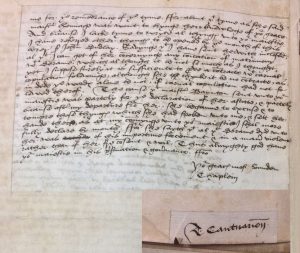

In a fascinating letter held at The National Archives written by Cranmer to the king, he describes his interview with Katherine in striking detail. Cranmer found her in a state of severe emotional distress (described as a ‘franzy’) as the gravity of her situation became apparent. She was in ‘such lamentation & hevyness, as I never sawe no creature’, almost inconsolable as she continued to ‘whyne in a great paine a longe whyle’. Eventually, the archbishop calmed her and managed to extract an admission of guilt before she broke down again.

But as he closed his account of the interview to Henry, Cranmer made it clear to the king that Katherine revealed she had not sought Dereham’s affections but instead what ‘he dyd unto her was of his importune forcement & in a maner violente rather than of her free consent & wil’.[ref]4. Catalogue reference: SP 1/167, f. 121 [/ref] This could suggest that Katherine’s sexual relationships with Dereham and Culpepper were borne out of necessity; she might have been forced into ‘buying’ their silence to hide her previous sexual relationships from the king.

- Cranmer’s account of his interview of Katherine Howard to Henry VIII (catalogue reference: SP 1/167, f.131)

- Cranmer’s account of his interview of Katherine Howard to Henry VIII (catalogue reference: SP 1/167, f.131v)

While the revelations were a surprise to Henry, the situation also caused a stir among the wider court and the flurry of activity did not go unnoticed by the foreign ambassadors. In a letter dated 11 November, Charles de Marillac, ambassador for French king Francis I, reported how Henry summoned his council at midnight and kept them in session throughout the night. Perhaps, Marillac speculated, there was ‘bad news from Ireland’ but this rumour quickly evaporated, as did any suggestion of trouble in Scotland. The ambassador pondered whether Henry was now seeking to dispense with Katherine Howard. While such speculation was correct, the underlying reason was unexpected.[ref]5. PRO 31/3/12, dated 11 November 1541, printed in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 16, 1540-1541 (London, 1898), no. 1332, 613-615[/ref]

Punishment followed swiftly for Dereham and Culpepper, who were tried in King’s Bench and sentenced to execution after being found guilty of high treason.[ref]6. Catalogue reference: KB 8/13/1, f. 12 [/ref] How to proceed against Katherine was evidently less straightforward: although she was indicted, she was not brought to trial. The charges against her were clear, however, having admitted her attachment to several men before and during her marriage, and she was accused of living an ‘abominable, base, carnal, voluptuous, vicious life’.[ref]7. Catalogue reference: KB 8/13/2, f. 20[/ref] In the end, she was condemned under a bill of attainder introduced to the House of Lords on 21 January 1541 which Henry signed in absentia on 11 February. She was executed on 13 February alongside Lady Rochford.[ref]8. Journal of the House of Lords: Volume 1, 1509-1577 (London, 1767), 167-168[/ref]

The documents held at The National Archives indicate that Katherine Howard made the unforgiveable mistake of trying to deceive the king. Even though she might have been forced into certain sexual liaisons and in spite of the fact that she showed repentance, Katherine still paid the price with her life.

Is not Culpepper spelt with one ‘p’?.

As in Culpeper.

Hello David, thank you for your comment. The spelling of names in the sixteenth century was not standardised; we decided to modernise the spelling to ‘Culpepper’ for consistency. Best wishes, Marianne

I live near Lincoln and am also very interested in the life of Katherine Howard. I have always believed she and Henry stayed at the Bishop’s Palace in 1541, but Lucy Worsley said it was at the castle. Could it be that they stayed at both locations? Thank you.

Hello Marilyn, thank you for commenting on the blog. The information that we have about Henry and Katherine’s visit to Lincoln suggests that on the 9th August 1541 they were met by the Mayor of Lincoln at the Bishop’s Palace and that they dined there, which strongly suggests that they also stayed there overnight. There is reference to Henry visiting the castle the following day. Best wishes, Marianne