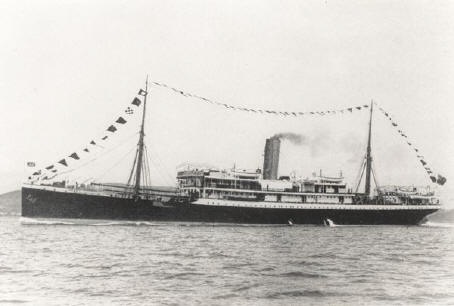

SS Mendi (image: WikiCommons)

The sea was calm on the afternoon of 20 February 1917 as the SS Mendi left Plymouth harbour for Le Havre under the command of Captain Henry Arthur Yardley. Acting as escort was the Royal Navy destroyer HMS Brisk. Below decks were over 800 members of the South African Native Labour Corps, bound for service on the Western Front. They had been recruited from across South Africa and had travelled on the Mendi from Cape Town via Nigeria.

Although the weather remained calm during the night, dense fog gathered making visibility very poor. By 04:00, as the Mendi passed the Isle of Wight, Yardley had cut the ship’s speed to slow and was regularly sounding the ship’s whistle. These were busy shipping lanes and the thick fog had created a dangerous situation.

At around 05:00 on 21 February, officers on the bridge heard the engines of a vessel close at hand. Out of the fog loomed the bulk and lights of a much larger ship. The officers ordered the engine room to reverse, but massive bows struck the Mendi and slashed through its steel hull. They penetrated a forward hold, where many Labour Corps men were quartered. This was the cargo ship SS Darro, travelling at its full speed of 12 knots. What happened next is revealed in evidence gathered by a Board of Trade investigation.

The Mendi listed steeply to the right and began to sink, so that only a few of the lifeboats could be released and only two were in the end successfully launched. In the dark and confusion, the Labour Corps men began to struggle out of the Mendi’s hold.

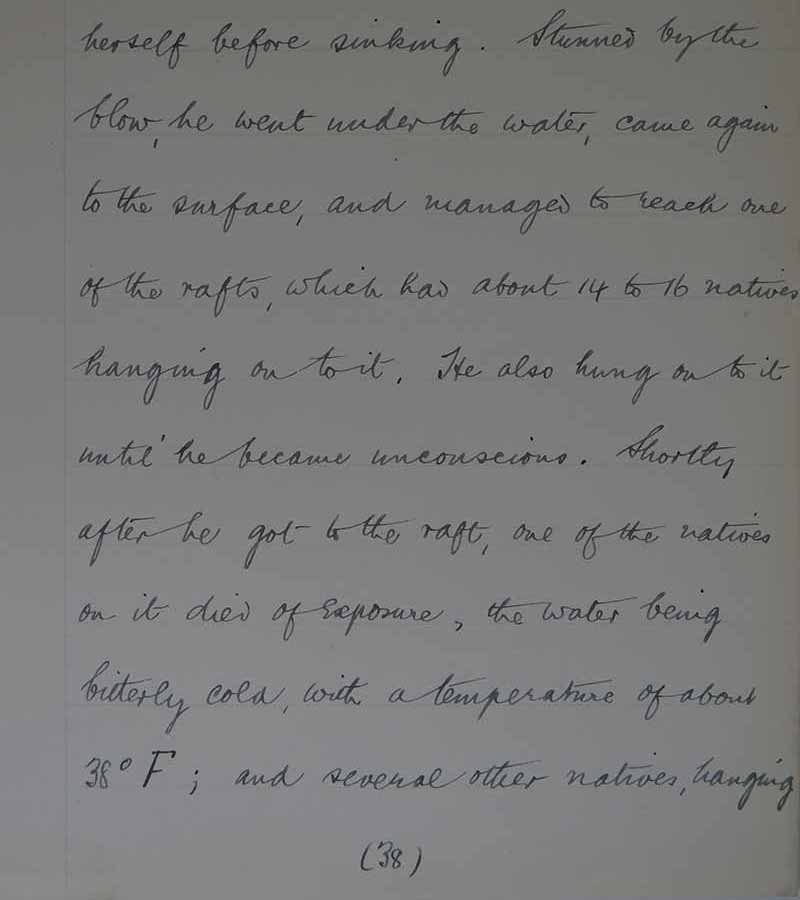

A witness reported that they set about ‘getting out the rafts, as if at drill’. Others slid down the deck into the freezing water. Some were picked up by lifeboats dispatched from HMS Brisk or clung to rafts, but many drowned or died of exposure. The water was too cold for swimmers to survive for very long. The Mendi’s captain recalled the effects of the cold on the men:

‘Shortly after he got to the raft, one of the natives on it died of exposure, the water being bitterly cold, with a temperature of about 38F; and several other natives, hanging on to it, dropped off…’

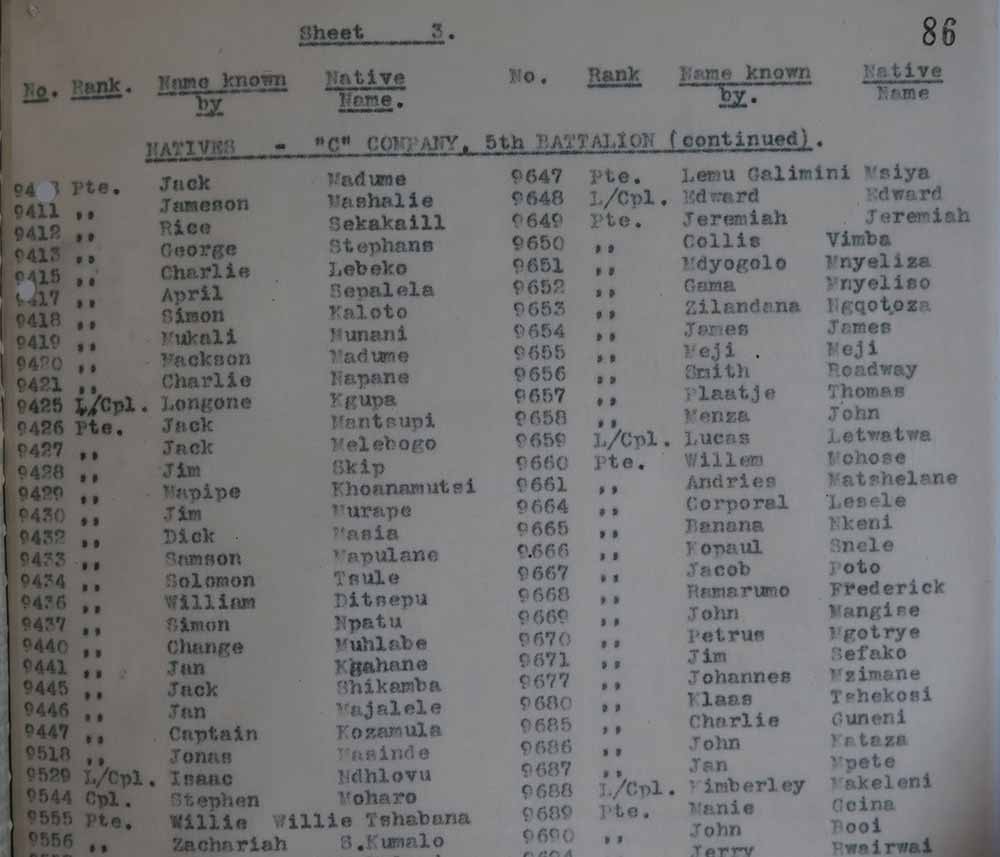

A South African Lieutenant Hendrik Lawrens Jansen van Vuren reported that many of the Labour Corps never even appeared on the deck of the ship. In fact, the collision had jammed the doors of an area near the front of the ship and many were unable to escape. They were still there when the Mendi sank, about 20 minutes after the collision. It was later calculated that 616 members of the Labour Corps died, together with 30 of the British and Sierra Leonean crew.

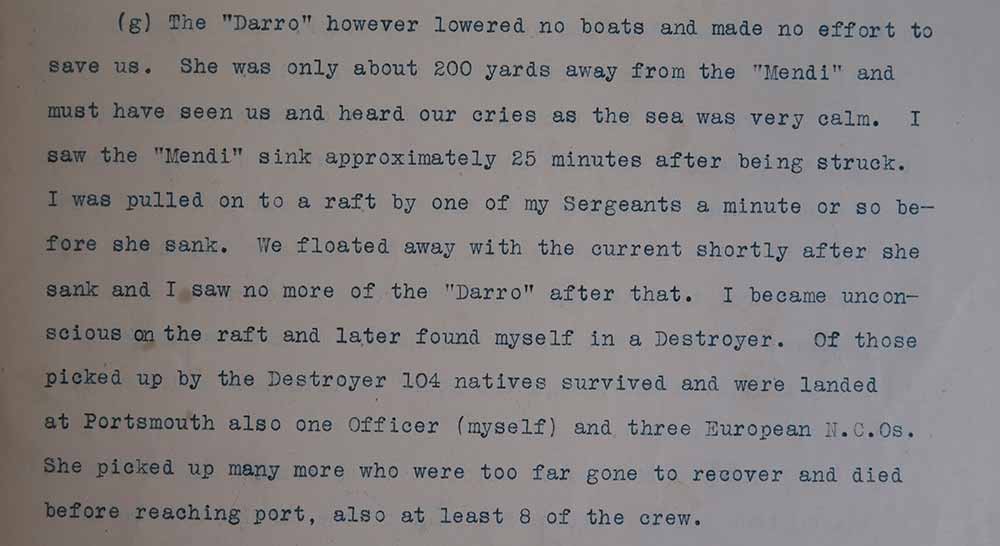

Jansen van Vuren evidence was damning about the conduct of the SS Darro’s master, Captain Henry Winchester Stump. The Lieutenant attested that:

‘I could see that the ship would very soon sink. I could see another large vessel (the “Darro”) about 200 yards away from us and as the sea was perfectly calm I ordered my men in Sixosa [Xhosa] to jump overboard and get away from the “Mendi” before she sank… I ordered my men into the water in the sure belief that the other vessel which I learnt was the “Darro” would lower her boats and come and pick them up.’

Evidence of Hendrik Lawrens Jansen van Vuren (catalogue reference: MT 9/1115)

But the Darro never lowered its lifeboats. Stump later explained that he was unaware that there were men in the water following the collision. He said that it it did not occur to him dispatch the lifeboat, which he claimed would have been lost in the fog.

List of the South African Native Labour Corps men who died in the disaster, sent to the South African government (catalogue reference: CO 616/75)

The inquiry placed the blame for the collision firmly upon Stump. Darro had been moving at close to its maximum speed and failed to make sound signals under conditions of poor visibility. Furthermore, he had failed to come to the assistance of drowning men although he had caused a fatal accident and remained in the vicinity. Even after a lifeboat from Mendi reached Darro, the inquiry found, he did not send assistance. In spite of this, Stump was never charged and his sole punishment was the suspension of his licence for a year.

The South African Native Labour Corps played a key role in supporting the allied war effort on the Western Front. The South African government had been unwilling to arm black troops to fight white soldiers. It feared this would fuel African opposition to its segregationist policies. Nevertheless, in 1916 the South African Prime Minister, Louis Botha, agreed that Africans would contribute as labourers to relieve the shortage of workers supporting the campaign on the Western Front. Between September 1916 and 1918, some 21,000 black and mixed race South African recruits had worked on trenches, roads, railways, ports and harbours in France.

For black South Africans, the sinking of the Mendi was a great tragedy of the First World War. Throughout the years of segregation and apartheid in South Africa it became a symbol of unity and opposition, which was central to African nationalism. In South Africa it continues to be commemorated as strongly as ever. The Hollybrook Memorial in Southampton commemorates the deaths of those who died on SS Mendi, together with others who were lost at sea during the war.

The SS Mendi is such a fascinating part of history. There’s a production coming to Nuffield Southampton Theatres based on this story Friday 29th June – Saturday 14th July https://www.nstheatres.co.uk/city/ss-mendi-dancing-the-death-drill I can’t wait to find out more about this part of history.

The as mendi tragedy should be taught in schools. Probably it can bring ones amongst south Africans .