For the first time, resources are available to academics and researchers online on the origins of intelligence agencies MI6 and the CIA. The National Archives and British Online Archives have partnered in digitising records relating to the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in our joint project: ‘Secrecy, sabotage, and aiding the resistance: how Anglo-American co-operation shaped World War Two’.

The background

Franklin Roosevelt, 1939-1946. Catalogue ref: INF 3/75 pt 4

Isolated during the first years of the Second World War, Britain looked to the USA for support. President Roosevelt was sympathetic; however, apart from financial and logistical support in terms of weaponry and ships, there was little the USA could offer apart from sharing signals intelligence.

There was a large, isolationist current of opinion in the USA which sometimes coalesced or overlapped with the sizable minority of pro-German, or even pro-Nazi, opinion. This stymied Roosevelt’s desire to do more to support the British. In addition, he had no budget to create the kind of agency necessary to counter these opinions and organisations.

But the pro-German – and certainly the pro-Nazi – current would, if left, continue to affect public opinion and possibly even grow. It was also involved in intelligence gathering and sabotage, including against war supplies or food cargoes bound for the UK.

The solution

There was a need for broad collaboration between Britain and the USA in counter-espionage and intelligence-sharing. They also needed to counter Nazi propaganda, infiltration and fifth column activity (i.e. sabotage). The British were prepared to provide an internal counter-espionage and propaganda service if they had the backing of both Roosevelt and J Edgar Hoover, the head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

Agreement was made in principle between Prime Minister Winston Churchill and President Roosevelt. A Canadian, William ‘Bill’ Stephenson, was chosen to lead the British operation, and Hoover agreed to co-operate.

Although agreed at the highest level between Churchill and Roosevelt, the British and American collaboration in security and intelligence was not something that grew up overnight. It had to be planned and worked for on either side.

The service was known as the British Security Co-ordination (BSC): it was an off-shoot of the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS – commonly known as MI6). The headquarters were housed on three floors in the Rockefeller building in New York. Room 3603 became the principal home for William Stephenson’s ‘allied intelligence organization’, and for the office of Allen Welsh Dulles, the man who would later be appointed Director of the post-war CIA.

The BSC had an interest in protecting supplies of armaments being transported to Britain from the eastern seaboard of the USA, as well as the ships that would be carrying them. Propaganda was the work of SO1 (Special Operations 1), the propaganda arm of the recently founded Special Operations Executive.

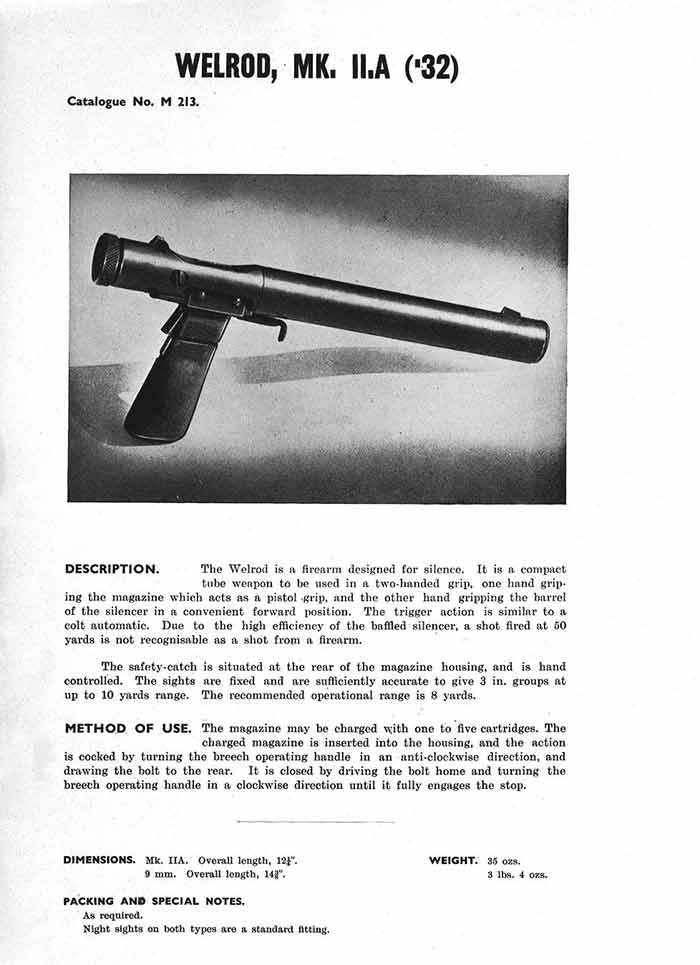

Much of SOE’s field-craft could be adapted from that of the former SIS Section D (D stood for ‘destruction’ – assassination, sabotage and black propaganda). Specialist training was provided for the (often inexperienced) civilian agents of SOE, and also the American and Canadian personnel trained at Camp X, Whitby, Ontario. Trainers included William Fairbairn and Eric Sykes, former officers in the Shanghai Municipal Police and experts in firearms and close combat, developers of the Fairbairn-Sykes fighting knife which was issued to British Commandos.

The BSC continued its role in the America until well after the USA joined the war. It was only in the early summer of 1942 that William ‘Wild Bill’ Donovan of the OSS took measures to reign in British Security activities in the USA and began to take a more active role in relation to South America. (Source: HS 7/72, 74, 75, 76, 78, 79, 80, and 82.)

Welrod firearm, MK. II.A (’32) Catalogue no. M 213, 1944. Catalogue ref: HS 7/28

BSC/SIS and SOE in South America

The BSC/SIS and SOE network carried out operations and propaganda work in Brazil and Argentina to negate the influence of Nazi propaganda by exposing the Nazis’ real plans for South America if they won the war.

Pro-Nazi radio stations set up by Nazi sympathisers were sabotaged or exposed and shut down by the domestic governments. Agents captured a map showing how the Nazis planned to divide South America if they were victorious: this was used to show governments the real intentions of the Third Reich. (Source: HS 7/73 and HS 7/79.)

STS 101/Camp X

The Americans also needed an intelligence and special operations organisation, and so training was provided for American agents who were to serve in OSS. This was the origin of STS 101 or ‘Camp X’ on the Canadian side of the border with the US.

It was better known to the Americans as the ‘School for Murder and Mayhem’, teaching all manner of techniques for physical endurance, orienteering, code-writing, using firearms and unarmed combat. (Source: Training syllabuses in HS 7/52 to 57.)

The relevance of these records to today’s research

The Anglo-American wartime special intelligence relationship paved the way for collaboration during the whole post-Second World War period. This material is full of interest for those studying the history of wartime and Cold War intelligence and special operations.

Digitisation is making a whole tranche of these records available online to academics and researchers around the world for the first time; previously they have only been viewable at The National Archives in Kew.

What information do the records contain?

This collection is arranged by country, then by subject, and the majority of these papers focus on the years 1940 to 1945. Most of these records are individual memos, reports or papers (not based on a pro forma) which summarise particular events. This is especially true of the SOE (HS) records. Each section of SOE had its own methods of record keeping, and these varied in format and efficiency.

The collection is also useful in throwing light on all manner of administrative as well as operational matters, and the background to the events described. It includes relevant records of missions, circuits and networks with appreciations by SOE officers in London. There is also material that reflects upon the respective war policies and aims of the two cooperating governments, which sometimes diverged.

Histories and War Diaries (HS 7) included contain the written narrative of events on a national or regional basis.

Visit the collection. (Access is available to academic institutions – individual licenses are not available for this collection.)

There will be a follow-up blog post, hopefully in April, dealing with aspects of the collaboration Worldwide.