Among the hundreds of thousands of designs held at The National Archives are many for musical instruments, or methods of improving instruments. These include examples that are still very much in use today, like the guitar and the upright piano, and others that have fallen out of use, such as the serpentcleide, or the English cetra.

These records help to illuminate the history of musical instrument making, particularly in the 19th century, when most of the designs for instruments were registered. They show how both well-known musical instrument makers and skilled amateurs designed and improved on instruments. We hold this material because the designs were registered for copyright – see our research guide for more information about registered designs.

The Ventura guitar, registered by A B Ventura, September 1849 (catalogue reference: BT 43/57/62625)

Angelo Benedetto Ventura registered a guitar and an ‘English cetra’. As a young man Ventura taught music to Princess Charlotte, daughter of George IV. He invented a number of variants on the harp and lute, as well as the guitar shown here, which he registered as an ‘ornamental’ design, meaning he was copyrighting the design rather than claiming a new function for his guitar. Records for ornamental designs are in the record series BT 43 and BT 44. He also registered ‘the English cetra’, a variant guitar (BT 43/57/62742). The V&A holds an example of one of Ventura’s cetras, and notes his claim that the cetra’s ‘splendid powerful tone’, was superior to the Spanish guitar.

Brass bands became popular in the 19th century, as advances in instrument making, mass production, and improvements such as the piston valve made instruments available to larger parts of the population.

As well as chapel and military bands, works and community bands became popular, with brass band competitions taking off from the 1850s. This is reflected in the registered designs, which contain a large number of designs for brass instruments. An instrument called an Antoniophone was registered by Samuel Arthur Chappell, the youngest son of one of the founders of Chappell’s, a famous instrument maker, retailer and music publisher based in London’s Bond Street.

The Antoniophone, registered by S Arthur Chappell, March 1874 (catalogue reference: BT 45/27/5558)

The shape was originally designed by Antoine Courtois, a maker of brass instruments based in Paris, and Chappell made changes to improve the sound. Samuel Arthur Chappell directed a series of concerts sponsored by the firm, and established a relationship with Gilbert and Sullivan in the late 1870s. This led to Chappell’s publishing most of their music.

The ‘new improved Regimental Cased Serpentcleide’ was designed for use by the British Army in India, and was advertised in the Indian News and Chronicle of Eastern Affaires of 1850. In the advertisement Thomas Key describes himself as ‘Military Musical Instrument maker to her Majesty, the Royal Dukes, and the Army’. The text accompanying the design tells us:

‘the bell or long tube of the instrument has heretofore been turned out of a solid piece of wood for the purpose of obtaining a fine sonorous tone; but when so constructed and exposed to the heat of a tropical climate, it is liable to split, whereby the tone is greatly deteriorated. To preserve these instruments from thus deteriorating is the object of the present Design.’

The wooden bell has a case of copper to protect it.

The new improved Regimental Cased Serpentcleide, registered by Thomas Key, 1850 (catalogue reference: BT 45/12/2379)

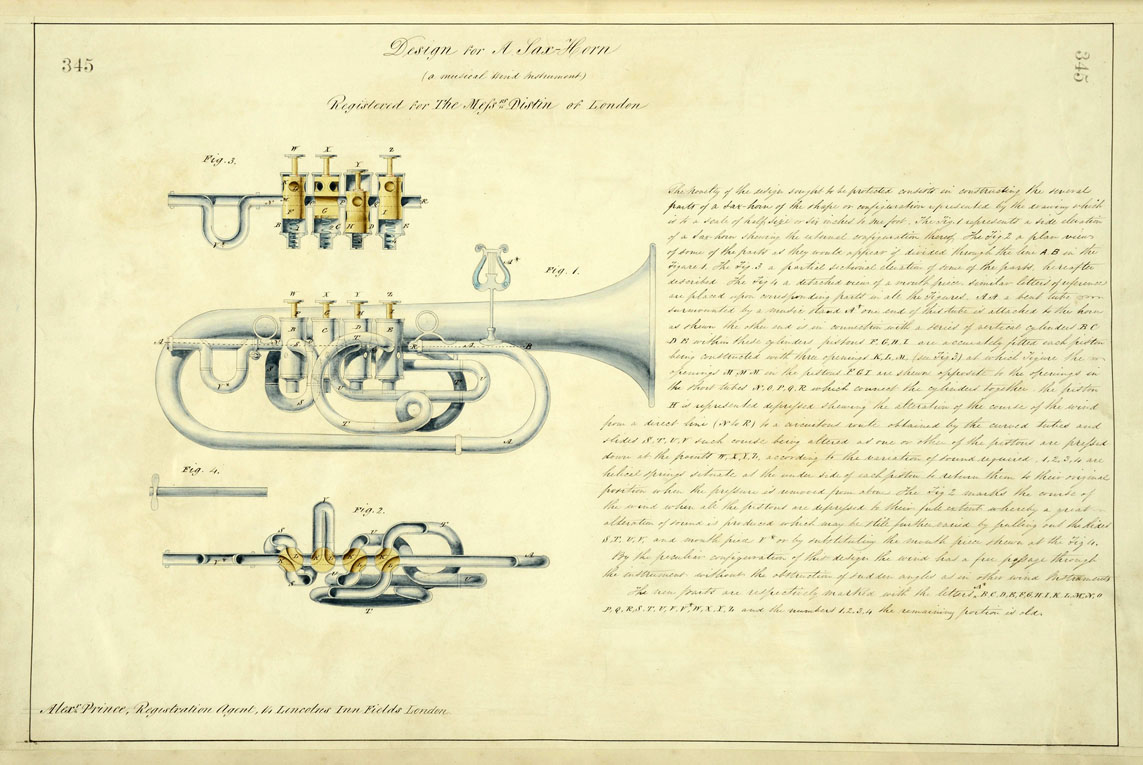

The well-known firm Distin’s also registered a number of designs, including this saxhorn, registered in January 1845. About 30 new parts are described for this instrument, which affords ‘a free passage through the instrument without the obstruction of sudden angles as in other wind instruments’. Through Distin’s, saxhorns became well known in Britain, and provided the basis of brass band instrumentation. The concerts of the Distin family were very popular and they became famous for their performances on saxhorns.

Sax-Horn, registered by the Messrs Distin, 1845 (catalogue reference: BT 45/2/345)

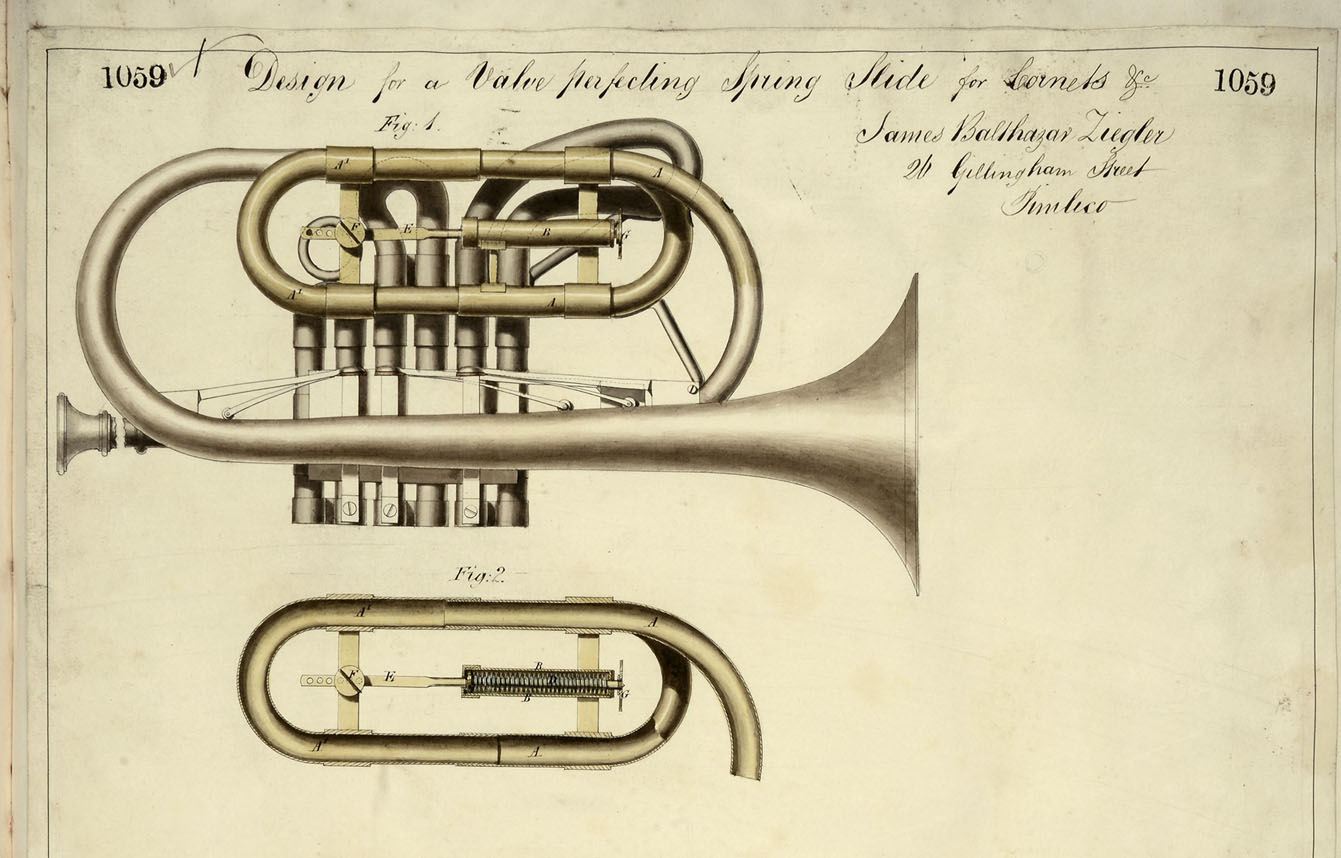

The potential of registered designs to shed light on the history of instrument making can be demonstrated by the design below for a ‘Valve-perfecting Spring Slide for Cornets’. Registered by James Balthazar Ziegler, a maker whose name hasn’t stood the test of time, it is a design for a cornet with double-piston valves and a spring slide. It is registered several years before a ‘cornet-a-piston’ with patent slide by Distin’s, suggesting that they might have been claiming credit for Ziegler’s invention.

The text that accompanies Ziegler’s design tells us that the object was:

‘to give the performer on Cornets or other valve instruments the power to sharpen or flatten any one or a given number of notes in the scale with facility . . . Any note in the piece of music may be flattened or shortened as required; and if from continuous exertion, the performer finds it an increased difficulty to play in perfect tune, he may by this improvement be considerably assisted.’

Valve-perfecting Spring Slide for Cornets, registered by James Balthazar Ziegler, 1847 (catalogue reference: BT 45/6/1059)

It was not only professional instrument makers who registered designs, but anyone who felt that they could improve an instrument in some way. These activities were part of a wider culture of invention, where advances in technology were celebrated and a spirit of enterprise encouraged ideas and innovation. Whereas in the present day there’s a feeling that you need to be qualified in a specific field to be taken seriously, in the Victorian period all sorts of people registered designs related to their interests.

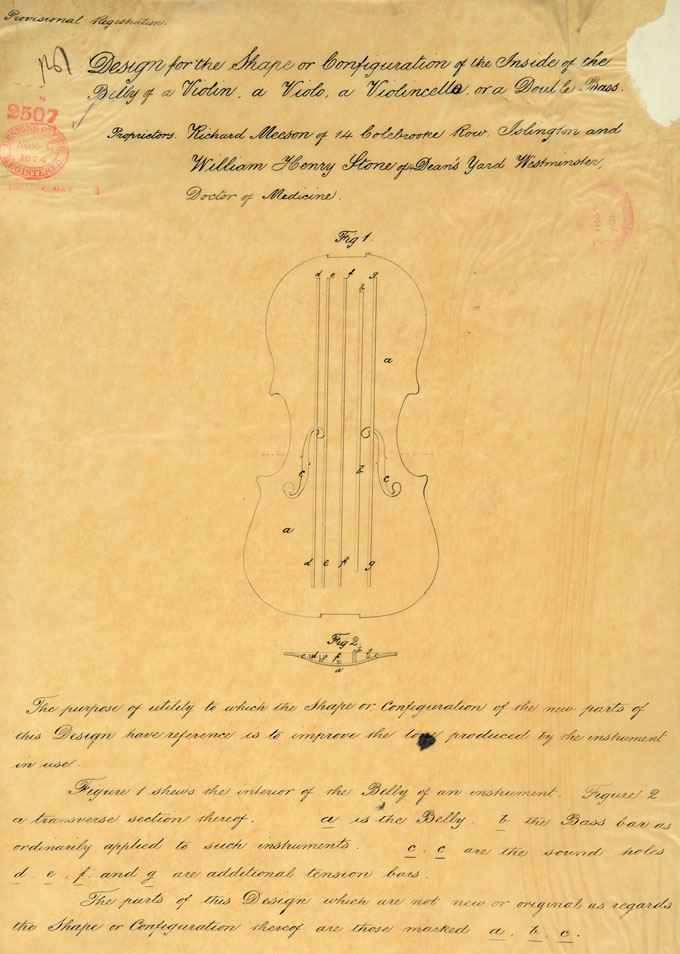

This design, which we’re told is ‘for the shape or configuration of the inside of the belly of a violin, or viola, a violoncello or a double bass’ was registered under the the Provisional Designs Act of 1850 (in BT 47), under which designs could be protected by copyright for a year.

Design for the inside of the belly of a Violin, a Viola, a Violoncello, or a Double Bass, registered by Richard Meeson, and William Henry Stone, Doctor of Medicine, 1875 (catalogue reference: BT 47/8/2507)

It was registered by Richard Meeson of Islington, and William Henry Stone, Doctor of Medicine, of Westminster. William Henry Stone was an eminent doctor, who was inspector to the Board of Health and Superintendant of Vaccination in Trinidad, before being appointed physician at St Thomas’s Hospital. His biography in Plarr’s Lives of the Fellows of the Royal College of Surgeons notes that at seven years old he showed what later proved a life-long tendency – that of branching off at a tangent from one pursuit to another. One of these pursuits was a love of music. As well as being a talented musician, he lectured on acoustics at the Royal Institution and published papers on ‘the scientific basis of music’ and ‘elementary lessons in sound’. The text tells us that the purpose of the design is to ‘improve the tone produced by the instrument in use’.

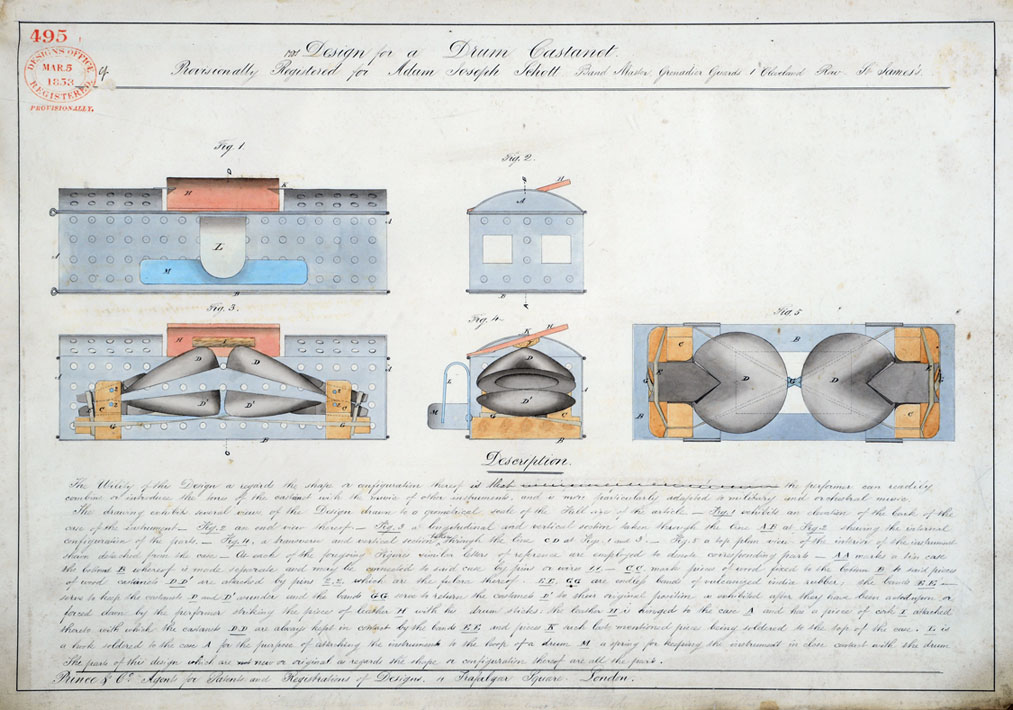

The design for a ‘drum castanet’, below, was registered by Adam Joseph Schott, Band Master in the Grenadier Guards, based at St James’s. We’re told that the purpose of the design is that the performer can ‘readily combine or introduce the tone of the castenet with the music of other instruments’, and it is ‘more particularly adapated to military and orchestral music’. Adam Joseph Schott was not only a Band Master in the Grenadier Guards. While stationed in Quebec he had instructed the string instrument maker Pierre Olivier Lyonnais in making instruments, and he played the cello in the Quebec Harmonic Society, as well as publishing three series of journals on military music. His father, Bernhard Schott, was the founder of the German music publisher Schott Music. Adam Joseph Schott established several international branches of the firm before leaving to pursue his musical career.

Drum Castanet, registered by Adam Joseph Schott, Band Master Grenadier Guards, 1853 (catalogue reference: BT 47/3/495)

Where few records of a company survive, the records held at The National Archives can sometimes help to fill historical gaps. The records of the piano makers Collard and Collard were destroyed in a fire, so a copyright registration (BT 45/7/1233) for one of their pianos provides important archival evidence. The design for a square pianoforte was registered in October 1847 when the firm was in the forefront of piano manufacturing. The new design element that is being copyrighted is that the keyboard is in the centre of the instrument, projecting from it.

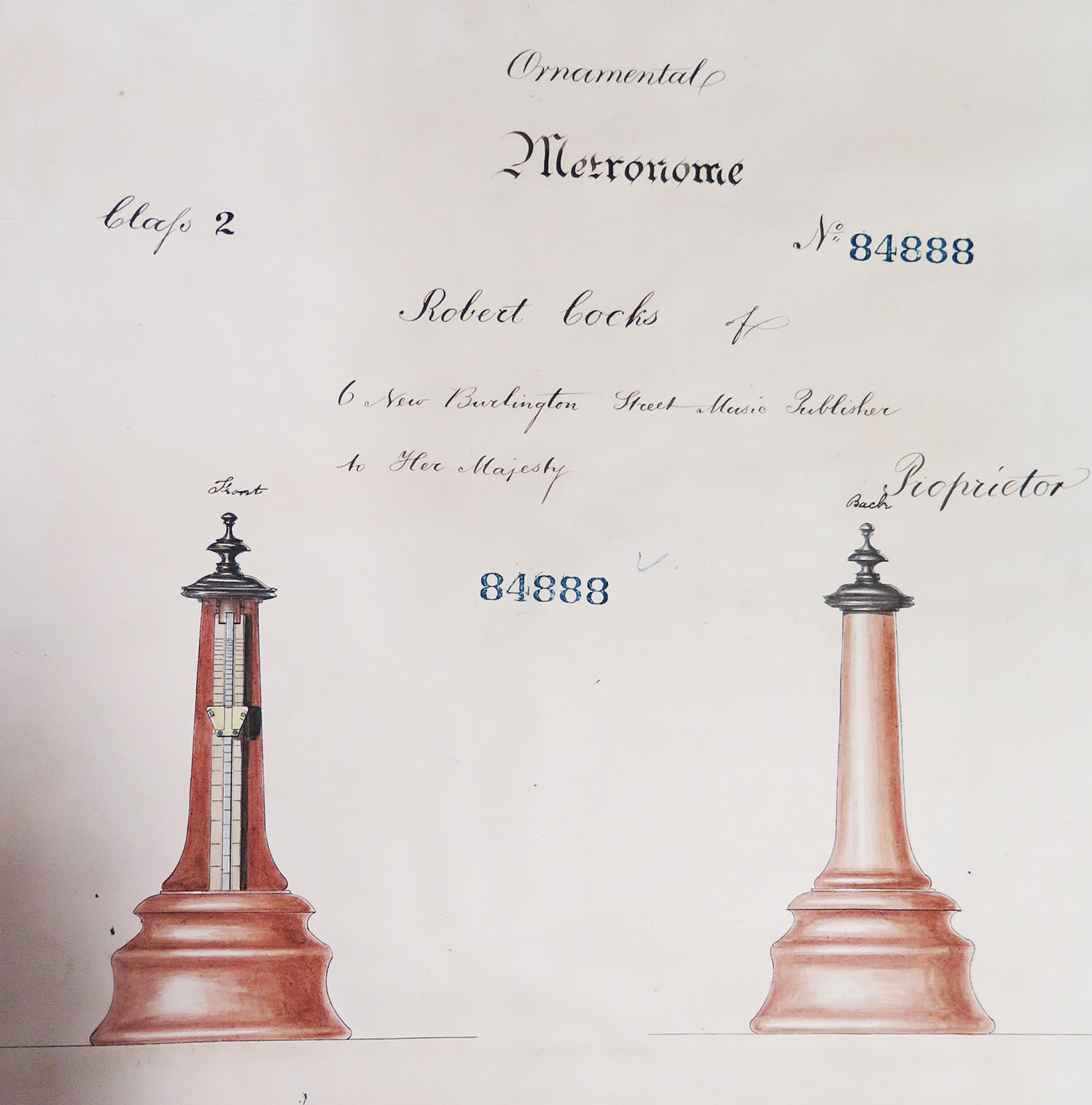

Metronome registered by Robert Cocks, 1852 (catalogue reference: BT 43/57/84888)

There are many other designs for instruments or improvements to instruments, of various degrees of significance, as well as items such as metronomes and music stands. There are the Boudoir pianoforte action, the Albert valve for cornet-a-pistons, trombones and ophicleides, the zither violina, and even musical bottles.

There are also gadgets designed to improve the learning and practice of music, like the geometrical key board for the pianoforte, by Miguel Theodore De Folly of Hampstead Road, London, which he claims ‘renders the instrument much more easy to learn’.

Learn more

A momentous question: decorating the Victorian home (podcast)

Inventions that didn’t change the world: a history of Victorian curiosities (podcast)

Julie Halls, Inventions that didn’t change the world, Thames & Hudson, 2014

Questions of attribution: registered designs at The National Archives (article – subscription needed)

this is something I have never thought of in relation to designing and then making these designs what skills to construct same back in the 1847 for example

Do you have anything on T E Bevan and co music company in Calcutta and Darjeeling