Events on 27 January to mark the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau urged us to remember what happened to Europe’s Jews during the Second World War; both as communities and as individuals. If we look further back, however, we also discover similar stories that should make us reflect for a little longer on the experiences of minorities in the history of our own nation.

In the autumn of 1290 King Edward I expelled England’s entire Jewish population. For two centuries the Jews had been prominent in national finance and local trade at key regional centres like York, Lincoln, Gloucester and London. Their relationship with Christians was occasionally difficult – subject to regular prejudice connected to crusading propaganda and the fluctuating levels of debt owed to Jewish moneylenders – but horrific outbursts, such as the massacre of York’s entire Jewish population in March 1190, were rare. Records here at The National Archives nevertheless reveal something of the pressurised realities of daily life faced by England’s medieval Jews.

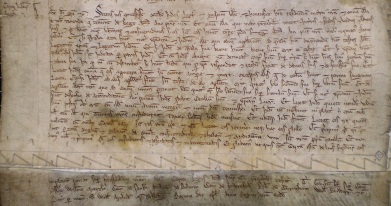

King John confirms Henry I’s liberties to the Jews, 1207 C 54/4, m. 5

Once William I invited Jewish merchants into England after 1066, they became collective property of the crown. King John confirmed much earlier liberties for the Jews in 1207 (C 54/4, m. 5).

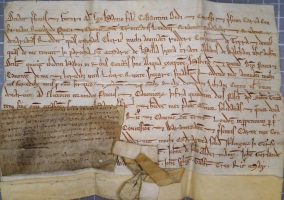

In return for such rights and protections, England’s rulers exploited the Jewish privilege to lend money at interest. Many early deeds suggest a largely productive business relationship between Jews and Christians. Contracts written in Latin for purchase of London property in the first half of the thirteenth century in E 40/13420 and E 40/13423, for example, contain some of England’s earliest surviving secular Hebrew text.

However, as the wealth of individual Jewish merchants grew, the crown targeted the entire community to fund warfare and to boost tax income. The wider population also followed this lead and agitated against the growing levels of debt owed to Jewish creditors.

This Latin grant by Hugh Peverel to the Prior and Canons of Holy Trinity, London includes the Hebrew contract or star of Aaron son of Abraham. Aaron releases his rights in the land irrespective of the debts owed to him by Hugh Peverel ‘from the creation of the world to the end thereof’. E 40/13204, 1222-1250.

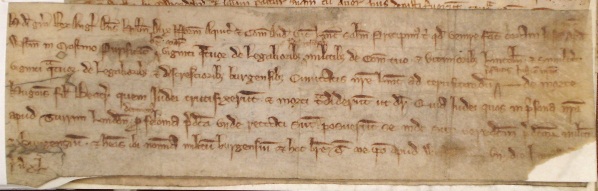

A deteriorating relationship between the two communities is suggested by the rise in reported anti-Semitic incidents from the 1230s onwards. Some related to the alleged ritual murder of children. For example, JUST 4/1/3, no. 168 relates to the alleged ‘blood libel’ case of Little St Hugh of Lincoln, who was found dead after a large Jewish wedding in 1255.

Over 100 Jews were condemned to death as a result of the crown’s investigation. All but one, Copin (in whose house Hugh had been found), were freed after the intervention of the king’s brother Richard, earl of Cornwall.

Instruction for a jury to inquire into the alleged crucifixion and killing of Hugh, son of Beatrice of Lincoln. JUST 4/1/3, no. 168.

Other evidence reflected the dominance of Jews in local trade and finance. The grotesque cartoon depicting Mosse Mokke in league with the Devil leaves little doubt about how the Jews of Norwich were viewed in 1233 (E 401/1565). Henry III’s restrictive statute of Jewry in 1253 also reflected what was happening elsewhere in Europe as Christian lords returned from the Seventh Crusade. The reaction to Henry’s clampdown was so strong that Elias l’Eveske, arch-presbyter of England’s Jews, asked if they could leave the country. This request was refused.

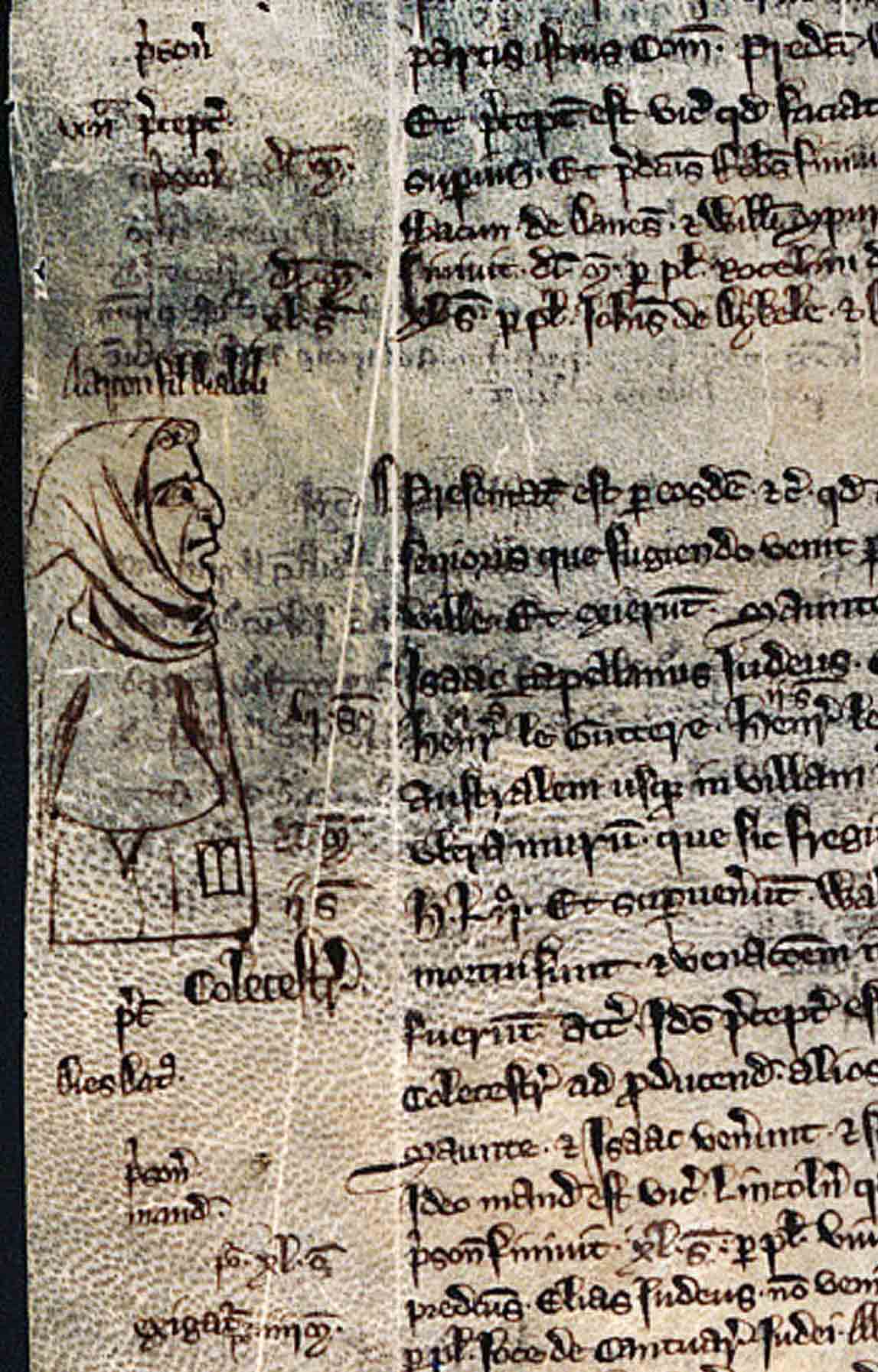

A receipt roll for the heavy taxation (tallage) of Issac fil Jurnet in Norwich, 1233. Isaac is drawn as a three-faced devil at the top of the image. Another devil, named as Colbif touches Mosse Mokke, Isaac’s debt collector (in his identifying spiked hat), and Mosse’s wife Avegaye. All the Jews in the image were accused of charging excessive interest on loans. Mosse Mokke was executed for coin-clipping in 1240. E 401/1565, 1233.

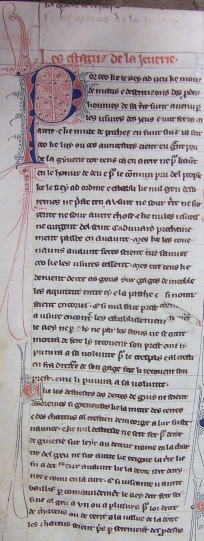

The French text of ‘Les Estatutz de la Jeuerie’ begins…Forasmuch as the King has seen that diverse evils and the disinheriting of the good men of this land have happened by the usuries which the Jews have made in time past… E 164/9, fol. 31d.

Things were a little different under Edward I after 1272. He became king when on crusade in Egypt and Palestine. Not only would he have met Jews there, he might also have discussed their status with other European leaders. Upon his return, one of Edward’s first demands was for an inquest into neglected royal rights, which of course included the Jews. The Hundred Rolls contain the returns to these inquiries in series SC 5. The new Statute of Jewry also passed in 1275 therefore revised the basis for the king’s relationship with Jewish communities. The text survives in a compilation book of statutes, E 164/9, fol. 31d.

This ‘detailed and radical’ Act re-emphasised many of the earlier restrictions. Jews had to live in specific areas of the king’s towns; those aged over seven were to wear the identifying badge of the double tabula; all aged over twelve years were to pay a tax of 3d each Easter; Jews could only sell property or negotiate debts with the king’s permission.

The earliest surviving image of the Jewish tabula badge – a piece of yellow taffeta cloth cut to resemble the shape of the blocks that contained the Ten Commandments – comes from a marginal sketch of Aaron ’son of the Devil’ in an Essex court case from 1277 (E 32/12, m. 2d). The image suggests that anti-Semitism remained prevalent as the statute came into effect.

The statute was radical in that it offered a route for Jews to make their living without usurious money lending. Some historians believed that this change brought about their economic emancipation. Others suggest that it removed the Jews from the close protection of the crown and left them open to the entrenched hostility of Christian merchants.

‘Aaron son of the Devil’ is written in Latin above a caricature of Aaron and next to record of a case involving two of his sons – who were part of a gang tried for illegal deer hunting in Colchester, Essex. The tabula badge is stitched to the front of Aaron’s clothes. Pleas of the Forest, Essex, 1277. E 32/12, m. 2d.

The Jews continued to be taxed heavily to finance Edward’s Welsh wars from 1277. The late 1270s also saw a rapid rise in prosecutions of Jews for coin-clipping. This allegation allowed suspicious Christians to view all Jews as a threat to the nation’s finances. It was perhaps believed because receipts from royal taxation of the Jews had declined tenfold since the 1230s. In 1276 the Jews highlighted their increasing poverty when they petitioned for clarification of what the new law actually meant for their collective future (SC 8/54/2655).

In his petition (written in French), Manasseh Ben Israel asks for the right to have a synagogue, a cemetery, to trade freely, for a person of quality to manage the process of Jewish immigration, for the Jews to have the right to decide their own dispues with appeals to the civil law, and to have revoked all laws previously enacted against the Jews. SP 18/101, fol 237. 13 November 1655.

By the late 1280s several short-term factors combined against the Jews. The tax of 1287 cost more to administer than it collected; Edward I was negotiating elsewhere for his war loans; and few among the Christian elite had a vested interest in maintaining the Jewish community. Crucially, in 1289 a new war with France in Gascony left the king in debt. Against a background of political problems he could only secure parliament’s grant of more taxation with the delivery of major concessions. The expulsion of the Jews was the price he agreed to pay. Since the Jews had been forced from Edward’s Gascon lands in 1287, it was a small step to organise their removal from England. In June and July 1290 orders were sent to sheriffs to begin the process and by 1 November 1290 all Jews had departed. [ref] 1. For the full story see, Richard Huscroft, Expulsion: England’s Jewish Solution (Stroud, Tempus, 2006). [/ref]

In 1290 there were only a few thousand Jews left to deport. The social and financial pressures experienced earlier in the century had already compelled many to leave. However, the decision to forcibly ship English Jews out of the country and out of the king’s conscience showed little human consideration. They were then scattered throughout Europe, often into equally hostile circumstances.

The last living link to the pre-expulsion Jewish population, Clarice of Exeter, died in 1358 in the House of Converts on Chancery Lane (the site of the Public Record Office). Tudor and Stuart rulers actively prevented the nascent growth of any small Jewish mercantile and medical communities in London and Bristol. It was not until 1655 that the Interregnum government’s new religious tolerance allowed Menasseh Ben Israel to travel from Amsterdam to begin negotiations for the open return of Jews into England. His simple request for the Jews to receive once again the protection of the English state only reflected the persecution they had continued to suffer elsewhere in Europe (SP 18/101, fol. 237).

What piece of music was Yasmin Levy singing during the broadcast of this piece on March 10th please?

Thanks for your comment, Samantha. The producer of Making History has told me that the music was Shoef K’mo Eved from the album Libertad (2012).

Any further comments about the broadcast piece related to this blog should go to the BBC Making History team directly:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b006qxrc/contact

[…] Below, two additional personifications echo and intensify the antithetical positions of these two figures. In a roundel below Ecclesia, the fair-skinned figure of Life (at far left) gazes calmly across the composition at Death, whose dark complexion and hook nose are seen in caricatures of Jews in other twelfth-century images. […]

I never knew any of this

Thank you

This is fascinating and has encouraged me to research Jewish History in towns and cities in the UK. North Wales being of particular interest due to existing place names. Thank you.