Why do people keep records? After all, the results of the decision to gather and store thousands – or in our case millions – of documents takes considerable amounts of time, money and space.

The National Archives’ current role is set out in our Statement of Public Task. Fundamentally, we hold documents for the purposes of:

- accessioning records

- preserving collections

- making collections accessible

This fulfils our legal obligations defined by the Public Record Office Act 1838, Public Records Act 1958 and associated legislation. Our records show, however, that the question of the purpose of record keeping was considered long before it was enshrined in law.

Conquest and supremacy

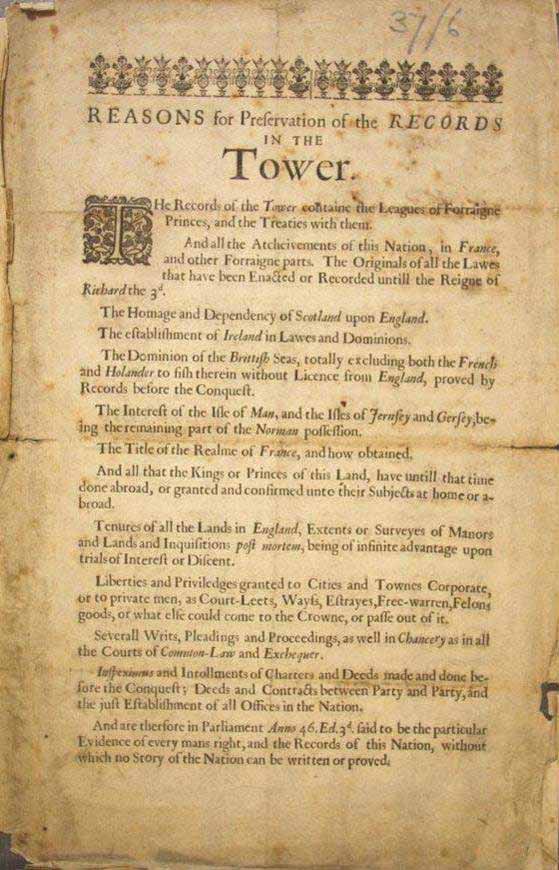

One example of this is SP 9/37/6, a broadside (a piece of parchment printed only on one side) produced in the late 17th century. It lists 13 ‘Reasons for Preservation of the Records in the Tower’.

The image shows a single sheet (a broadside) printed by the crown, probably in the 1680s, to explain why documents of state were stored in the Tower of London (catalogue reference: SP 9/37/6)

Before the foundation of the Public Record Office in Chancery Lane in 1838, the Tower of London was one of a number of locations used to house government documents, specifically those of the Chancery and Exchequer. From the late 14th century onwards the Wakefield Tower was being used to store documents and was known as the Record Tower.

The broadside reveals a very different set of priorities to what we are familiar with today. While there is some sense of the importance of documents as a historical record, the crown was, above all, interested in the preservation of diplomatic treaties and the supremacy of England over its neighbours.

The very first reason given for document preservation is ‘The Records of the Tower containe the Leagues of Forraigne Princes, and the Treaties with them’, while clause seven moves to ‘The Title of the Realme of France, and how obtained’ – even though the reality of this claim had long since been forgotten.

Item six covers England’s interest in the Isles of Man, Jersey and Guernsey, while – perhaps most controversially to modern eyes – clauses three and four refer to the ‘The Homage and Dependency of Scotland upon England’ and ‘The establishment of Ireland in Lawes and Dominions’.

Legal knowledge

The maintenance of a record of law was also of great concern.

The second item, for example, states that the archive in the Tower included the originals of ‘all the Lawes that have been Enacted or Recorded’ until the reign of Richard III. This remains true to this day: while most original acts of parliament from 1497 onwards are held at the Palace of Westminster, nearly all of the medieval material is with us here at Kew. Clause 11 meanwhile refers to the many writs, pleadings and proceedings that were produced by the central law courts, including Chancery, documents which still form a large part of our collection.

Other entries focus on the importance of the records in upholding the legal rights of the individual, including:

- the documentation relating to the ownership of land and ‘inquisitions post mortem’ in clause nine

- the liberties and privileges granted to cities and towns in clause ten

- the enrolments of charters and deeds in clause twelve

In the late 17th century then, these were active as much as historical documents. Were there to be a dispute, these records could be called upon as proof of centuries old agreements.

The fifth clause, for example, states that documents should be preserved because they contain

‘The Dominion of the Brittish Seas, totally excluding both the French and Holander to fish therein without Licence from England, proved by Records before the Conquest’

It is known from his diary that in his capacity as Clerk of the Acts at the Navy Board, Samuel Pepys requested an Exchequer official, Mr Falconberge, ‘to look whether he could out of Domesday Book, give me any thing concerning the sea, and the dominion thereof’.[ref]1. www.pepysdiary.com/diary/1661/12/21[/ref]

Pepys, however, was an exception. There was no obligation to provide access, organise, or conserve records in a systematic fashion. In 1830, the miscellaneous records of the King’s Remembrancer were described as ‘a mass of putrid filth, stench, dirt and decomposition’.[ref]2. A. Lawes, Chancery Lane 1377-1977: ‘The Strong Box of the Empire’ (Kew, 1996), p. 16[/ref]

Despite this there is a sense of the more familiar understanding of the documents as a historical record – albeit one that highlights England’s activities overseas! Clause two states that they contain, ‘all the Atcheivements of this Nation, in France, and other Forraigne parts’ something which is echoed in item eight, where it is highlighted that the records include ‘all that the Kings or Princes of this Land, have until that time done abroad’.

Magna Carta

Most interestingly, in light of last year’s 800th anniversary celebrations, the final clause states that the overall importance of the preservation of the records was that they are particular evidence of every man’s right as described in the parliament roll of 46 Edward III, 1372. This refers to is the rights set out in Magna Carta, which were entered on the parliament roll at this time.

The reasons for the preservation of government documents have changed dramatically since the 1680s. Emphasis has shifted from law and conquest to conservation, access and the historical record.

Despite these differences, however, what this document shows is a shared understanding by record keepers across the centuries of the importance of preserving the ‘Records of this Nation, without which no Story of the Nation can be written or proved’ – and few could argue with that.

Whilst the vast array of records was kept long before the PRA 1838, and before the PRA 1877 (describing which sorts of records did not and should not be kept) there were copies of publications which were duplicated elsewhere.

The keeping of the records of the Exchequer (long before Treasury was put into Commission) were kept for financial accounting reasons and continue. An example of why records were kept were to stop searches for the same subject, an example was the search for King John’s treasure lost in The Wash when officials went to the British Museum to trace the journey of the Royal Train, an issue which arose in the 1970s or why money was paid for the Perpetual Payments going back to the Middle Ages. As far as Treasury were concerned it was not until 1782 that a proper system of record keeping stated and the failures of 1829 when the business of the Treasury was held up because the previous papers could not be found, a classic clash from those who had to find the papers operating separately from those who looked for the papers, a situation not different from the 1981 records onwards.

The keeping of records does these das hold people to account for their decisions or has been noticed recently comments made about issues like Black enterprises, in fact they can be amusing, one Treasury official thought that Margaret Thatcher’s demand that no expenditure on law and order, especially for the police, should be cut was thought to be an April Fools’ joke!.

[…] UK National Archives – The Records of this Nation http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/records-nation/ Emmaus Mossley passes on rare football records donation to national archives […]