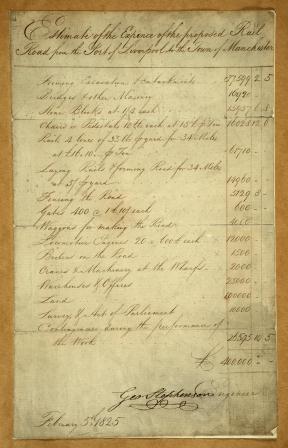

Estimate of the cost of building the Liverpool to Manchester railway (catalogue reference: RAIL1148/1 (6))

Today we tend to take the railways for granted. If we talk about them at all it is usually to complain about trains being late, overcrowded, or cancelled. Train travel seems to have have lost its magic for many people. Familiarity has bred contempt because for as long as you have been alive there has always been the option of travelling on a train.

But imagine what it must have been like 180 years ago when the first passenger steam train was introduced, and riding at high speed through the countryside was a new and exciting experience.

Well you don’t have to imagine it – there is an eyewitness account. Two weeks after the Liverpool and Manchester Railway opened on 15 September 1830, a man, known to us only as E.W.S, took a trip on the new contraption. He wrote a charming account of his experience for the Wath-upon-Dearne (West Riding of Yorkshire) publication ‘The Village Magazine’.

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway was the first railway in the world to run a regular passenger service, and the first to be powered by steam engines. It ran luxurious carriages for those who could afford the fare and open top trucks for ordinary passengers. E.W.S took a snug seat in one of the posh carriages.

He starts his description of the 32 mile journey from Manchester to what he calls ‘the rising and flourishing port of Liverpool’ as follows:

‘For the first quarter of a mile, as if to prepare us for the tremendous extreme that we were soon to encounter, our speed was not more than 6 miles an hour. We then began to find that our progress was increased by every succeeding stroke of the engine; so that in a very few minutes we were flying through the country at the rate of twenty five miles an hour.’

He turned to a fellow passenger and said, ‘Where now are the labours of the horse; and how insignificant do his exertions appear, when compared with the principle by which, meteor-like, we are now shooting through the air?’

E.W.S was amused at how things appeared as he travelled past them. Passing groups of people, he was unable to:

‘…discover whether they possessed the natural appurtenances of the human face divine, or whether, after the fashion of the aborigines of our country, they chose to mantle themselves in the skins of beasts. Objects near us made up one continuous line, the earth, with its iron stripes, seemed like a vast ribband unrolling itself as we went along; but whether the immediate surface of the road, over which we were passing, was covered with pearls or pebbles, it was impossible to ascertain without endangering both head and eye.’

Fence posts, rails and gates appeared to be ‘starting from their holds and dancing to greet our arrival’ while trees and cottages ‘were seen for the moment, and unless the position of the eye was altered, instantly lost’.

When a train passed in the other direction,

‘…the most extraordinary sensation to the passenger happens. The effect is only for a moment, but is nevertheless formidable. You see them advancing; perhaps both sets [of carriages] are proceeding at twenty miles per hour, making together a comparative speed of forty miles for the same space of time. They approach like an arrow out of a bow – a glimpse – “The arrow is flown – the moment is gone”; and you are left in a state of excitement not to be described. That you have passed something you are quite certain, and you may believe them to be carriages similar to those you are travelling with; but whether laden with blacks or whites – Irish butter or Yarmouth Herrings, it is impossible to ascertain. All you know is, that the object you saw approaching has passed and gone.’

When his train stopped to take on water E.W.S noted that passengers spoke to the conductor as if he were in charge of a stagecoach – with horses, telling him to drive on, pull up or hold hard, ‘as if changing horses at a post-house on a turnpike’.

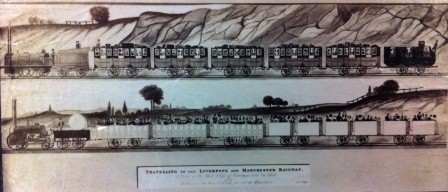

Drawing of the first Liverpool and Manchester railway trains (catalogue reference: COPY 1/374/31)

Further down the line the appearance of workshops and well-built houses signalled that he was nearing Liverpool. The train was stopped just before they entered the uphill tunnel to the Crown Street terminus at Edge Hill. At this point he was rather surprised to see the engine being uncoupled:

‘As if to humble us, and bring our ideas to the ordinary ratio of progressive motion and travelling speed, we had yoked to our splendid carriages, without any notice whatsoever – four high-mettled donkies! After comparatively flying, was not this humiliating – humiliation scarcely to be borne? But the patient animals performed their office safely, if not swiftly; and after groping in the dark for some three or four minutes, the daylight of heaven again broke upon us.’

E.W.S completed his description of the journey by stating ‘I secured my luggage, jumped into a stage, and in little more than an hour and a half after leaving Manchester, found myself at the King’s Arms, Castle Street, Liverpool. Jan. 28th 1831.’

The same journey can be completed today in a little over half an hour. E.W.S states that the average speed over the journey had been 20 miles an hour, reaching 30 miles an hour in places where the ground was good and level. The writer would seldom, if ever, have experienced speed like this before, certainly not over such a long journey. Stagecoaches of the day travelled an average of 10 miles and hour, and horses tired quickly if ridden at full speed. The whole exhilarating experience appears to have excited him, like a modern child on a theme park ride.

So next time your train is delayed, try passing the time by imagining you had never ridden on a train before. Try to capture the sense of childlike wonder and excitement which gripped our Victorian adventurer, Mr E.W.S – whoever he was.