An example of what a 1930s powder puff would have looked like, though the box itself is from a later date (roughly 1947), from the Auckland Museum’s online collection.

On the evening of Saturday 14 November 1936, 28 year old Arthur Agate – on a rare night off from work – had a few drinks at his friend Ronald Simon’s house in London Fields, Hackney, and then caught the bus into central to go to a club that was reportedly unlike ‘any other place in London’.

‘Billie’s’, as it was affectionately termed, was situated on a street off the Charing Cross road, just a stone’s throw from the residence where decades later both David Bowie and the Rolling Stones would make their first recordings. In 1936 however the entertainment was strictly cabaret: a bell marked ‘Members ring once’ opened the club’s bottle-green door into a large room, densely clouded with smoke from cigarettes and filled with people dancing. Spirits were often high and silly at Billie’s: the stage was frequently occupied by a piano player called Gordon who had a tendency to lift up his kilt and flash the audience during his set. Less bawdy nights would see the famous music hall performer Fred Barnes top the bill, or Barry – a man who sang songs in falsetto while wearing an evening dress.

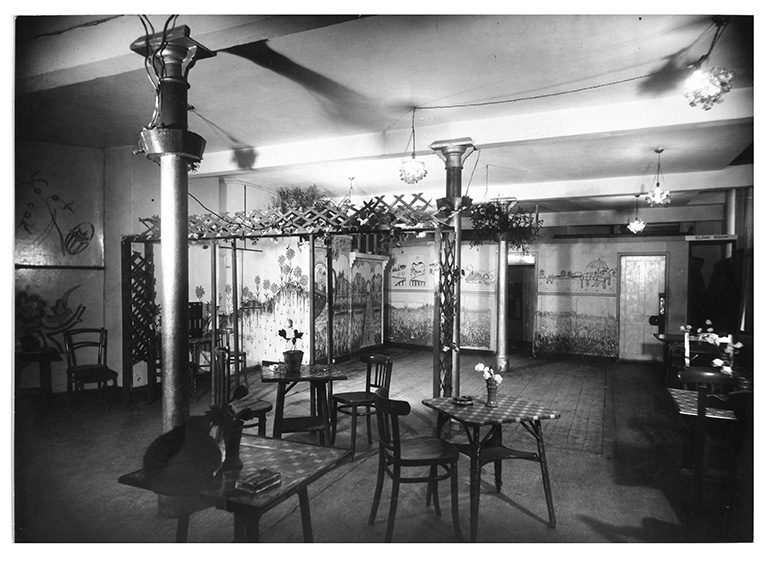

A photograph of the interior of Billie’s Club, November 1936 (catalogue reference: CRIM1/903)

Billie Joyce, the club’s owner, wore a large metal ‘B’ on the front of her blouse and would often take a break from serving gin and lime to take over on the jazz drum, or dance with members of the club. Her colleague James Rich would introduce the acts, and when the lights dimmed between performances club goers emboldened by the darkness would try to raise a few extra laughs by shouting out crass jokes. A popular act was a man who danced the rumba while wearing a transparent chiffon skirt and a thin black strip of cloth across his chest; a performance that would prompt Connie, one of the barmaids, to shout: ‘Where could you see anything like that for a fourpenny drink!’

Billie would make the effort to introduce a newer face to one of the regulars, but many of the members already knew each other: for Charles Hedges and Frederick Summers, this evening was their third consecutive Saturday at the club, where the dancing would often go on until 03:00. When Ronald arrived, Charles and Frederick were already on the dance floor, where they coerced him into a conga line and danced across the club until Charles thrust into Frederick and subsequently knocked Ronald flying on to the floor.

The three men were completely unaware that they were being watched at this point. Saturday 14 November marked the final evening in a series of undercover observations on Billie’s undertaken by the Metropolitan Police. A month earlier, an anonymous note had been sent to the Met about the club, which had been open for less than a year, urging the police to immediately look it over. ‘Saturday is the night they make whoopee’ it said, ‘you have closed clubs for much less. Why let this filthy place run?’ Officers had already been keeping watch on the club since December 1935 after receiving a complaint alleging that ‘sodomites’ were using the premises, and after failing to find evidence of disorderly behaviour from the outside, had started to keep interior observations of the club from April 1936.

Kenneth Murray, a Detective Sergeant at Bow Street Police Station, had observed the premises for so long that he had become a regular at the establishment. His alias was convincing enough that on a previous evening one of the club members had asked Murray – who was operating under a different name – to dance, and after he had accepted remarked: ‘I wonder why this place has not been raided… perhaps the police do not know about it.’ Detective Sergeant Murray had already been at the club all evening when a team of officers entered the venue at 22:50, roughly an hour after Arthur and Ronald had arrived and ten minutes before the bar stopped serving alcohol. They reportedly caught several punters in compromising situations: Arthur was dancing with a man called William Hibbert, while Ronald was resting on a settee near the door with his left arm around the neck of a man called Frederick John Branch.

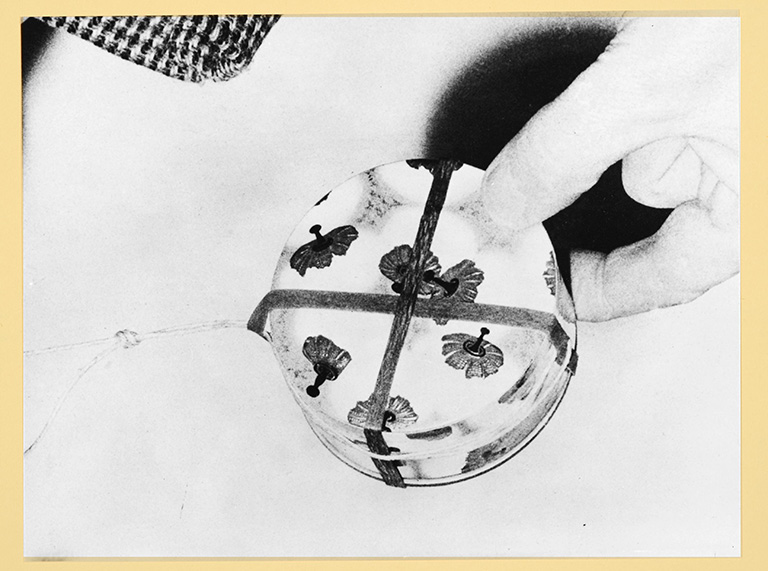

A drawing of a face powder carton, also from The National Archives’ image library (catalogue reference: WO195/15751)

Face powder packaging from The National Archives’ image library, dated 1907 (catalogue reference: COPY1/258)

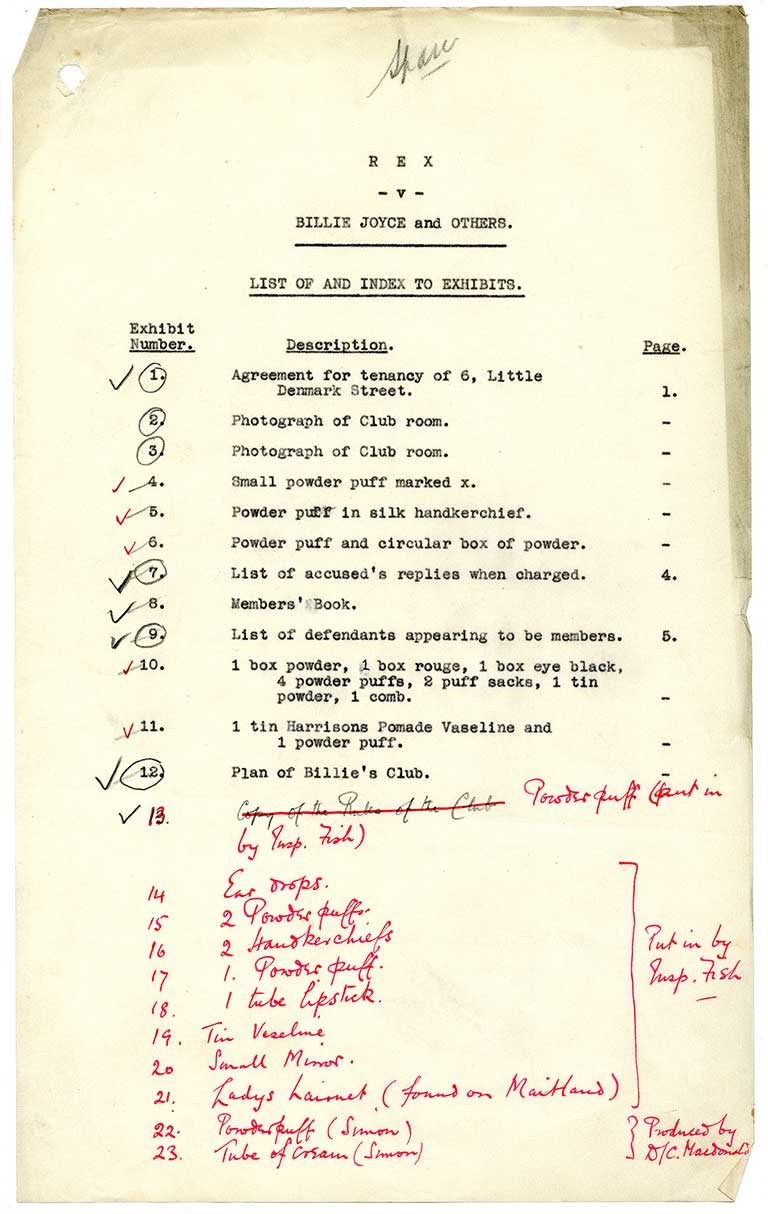

As it became evident that a raid was occurring, club goers broke apart and the music stopped. The opportunity for officers to catch men dancing or embracing had passed, and so police began to scour the scene for other forms of evidence. They observed the faces of the men present, noting that most were ‘rouged or powdered’, and used a piece of cloth to start collecting traces of the make-up, but then stopped when they realised it would take too long to take a sample from every defendant. Officers decided that it was quicker to log the names and belongings of those made up instead (both Arthur and Ronald were powdered, according to Detective Sergeant Murray), taking special effort to note those who carried a hair net, a nail pick, a powder box, or a powder puff in their pockets.

The police’s reports reveal the kind of observations and evidence they felt would reinforce the claim that Billie’s was an ‘immoral’ club, including accounts of what members wore, how they danced, and what they said to each other. Detective Sergeant Murray heard one man say: ‘I haven’t got any make-up on tonight, dear. Do I look alright without it?’ to which his companion replied, ‘You always look lovely’. Another officer stated that Connie, one of the bartenders, jokingly referred to a drink as a ‘whisky and sodder’.

He also reported that he had seen women at the club who ‘had the appearance of lesbians’, and that when a ‘half-caste man of about 25… a fairly regular frequenter of the Club’ sang a song in ‘a very effeminate manner’, his appearance prompted another man, sitting near to the officer, to exclaim ‘isn’t she gorgeous!’ An officer called George Miller felt it pertinent to refer to Billie’s colleague James as ‘the negro’, and report that when he ‘danced with the girl who assisted… behind the bar. He was holding her very tight.’

What’s fascinating about these reports is the way in which the actions of those present in the club at the time of the raid suggested that the defendants already knew how the police would interpret their possessions. One officer claimed that when they entered the club, Ronald jumped up and threw a powder puff and a tube of cream behind the settee, which the police then collected and later produced as evidence in court. PC John Brindley also reported that another of the prisoners ‘stood up, threw a box of powder and a powder puff under the piano, and walked to the other side of the room.’ From the way in which the cosmetics were offered as evidence in court, and were not questioned with regards to how they could prove ‘immoral’ behavior, it suggests they carried an implicit meaning that was understood by police, the public and the courtroom at the time in a way that seems unfathomable now – almost as if their presence at Billie’s was as significant as a blood-stained knife at a murder scene.

A list of evidence collected by police on the night of the raid. Ronald Simon’s name is listed next to exhibits 22 and 23 (catalogue reference: DPP 2/355)

There isn’t a single piece of photographic evidence within the files from the court case of the items that were confiscated from Billie’s; to understand what they may have looked like, or to what extent the accused men might have been made up, I spoke to Juliette Edwards, founder of the British Compact Collectors Society. She explained that cosmetics and the means of applying them have a well-documented history where women are concerned. Puffs were often made from the down of young geese, sewn into small delicate clusters, or from lambsdown (here’s a short British Pathé video showing how cheaper puffs were made in the 1930s). Advertisements from the time show how the pale powder (sometimes perfumed – one in Juliette’s collection still carries the scent of sugared almonds) was kept in compacts that women would purchase once and buy refills for. For those who couldn’t afford compacts, or didn’t want to carry them, it was possible to purchase a puff concealed within a tied-up handkerchief into which a little powder would be stored for a single application. Eyebrows were thin and black, rouge was patted onto cheeks – but how the men arrested at Billie’s might have bought and worn make-up is a much more difficult history to extrapolate. The officers’ descriptions of the cosmetics and how they were applied are vague, and were often contested by the defendants – possibly in an attempt to suggest that the police’s accounts of the event were unreliable, however. William Oakley, one of the men present on the night of the raid, said ‘I had no make up on my face… Donaldson [one of the officers] said I had pink powder on my face… powder found in ex[hibit] 6 is brown’.

To understand whether it was likely that the men at Billie’s were wearing cosmetics and how they might have applied them, it’s necessary to go beyond the statements made by police in these reports. In a pioneering TV programme made in the 1980s about life as a gay man in the 1930s, Gifford Skinner, a shopkeeper born in 1911, detailed his experiences:

George was mad about make-up… It was just brown powder bought from a theatre shop in Leicester Square. Once applied, we would ask each other if it was visible. ‘Yes’ meant that a layer had better be quickly removed. ‘No’ meant the addition of a little more powder; and so on to Liverpool Street.

Cosmetics and clothing played a key role in allowing queer men to identify each other in a society where same-sex relations were illegal: ‘certain accessories became homosexual signs of recognition, in particular suede shoes and camel’s hair coats’ wrote Skinner. At Billie’s, police noted the reoccurring ‘red and white spotted scar[ves].’ Florence Tamagne wrote in ‘A History of Homosexuality in Europe Vol. I: Berlin, London, Paris, 1919-1939’ that while a distinct style emerged in the 1920s and 30s that ‘allowed homosexuals to identify one another more clearly, it also put them at the mercy of a society increasingly skilled at reading through the codes.’

From behind a desk scattered with binders of cosmetics advertisements from the 1920s and 1930s, Professor Matt Houlbrook, historian and author of ‘Queer London: Perils and Pleasures of the Sexual Metropolis, 1918-1957’, explained that in order to understand how cosmetics were being considered as evidence in prosecutions against queer men, it’s imperative to understand the role cosmetics played in gender and sexuality politics at this time. In the 1930s, as a result of the rise of cinema stars and the products they wore to make their faces visible on camera, make-up had taken on new, more glamorous connotations – it was no longer the reserve of the ‘fallen woman’. Simultaneously, developments in industry had led to the production of affordable, portable products that allowed women to achieve a new level of transformation that had previously been unattainable. More women – and more ordinary women – were accentuating their faces and applying make-up in public than ever before: it was becoming a staple of a woman’s regime, tightly tied to the concept of modern femininity

Cosmetics were, as a result of being marketed at, bought and worn by women, deeply gendered – just as cigarettes had historically been marketed at, bought by and smoked by men (until tobacco companies saw an opportunity to use the suffrage movement as an opportunity to expand product sales by marketing cigarettes to women as ‘torches of freedom’). In an underground club in London in the interwar years, the meaning of a powder puff – or a lipstick, or rouge – shifted depending on the gender of the person possessing it: as a tool targeted explicitly at women, it was assumed that when a man used it, it became an attempt to attain the same thing the advertisements promised to women: femininity. To understand why it was more contentious for a man to be seen applying powder than for a woman to be seen smoking a cigarette in the 1930s, it’s necessary to understand how thinking around gender and sexuality intersected with the law at that time, and also against the collective memory of recent policing history.

In ‘The Man With the Powder Puff’, Matt Houlbrook explains that between the wars the power of cosmetics as evidence for prosecutions against homosexuals depended upon on the assumption that male ‘effeminacy’ was a sign of transgressive sexual desires. Male and female bodies were assumed to be ‘sexed’ in distinct ways – that masculine bodies desired females, and feminine bodies desired males. And therefore the effeminate man was assumed to possess ‘illicit’ sexual desires. As a contributor to ‘Between the Acts, Lives of Homosexual Men 1885-1967’ explains, the term ‘queer’ before the Second World War was commonly used in reference to effeminacy before it was used to communicate sexual preferences:

They might call you queer, but probably only because of the way you talked, but they wouldn’t think anything about sexually. They’d call you queer because they thought you was a bit girlish. But not because of the sexual act.

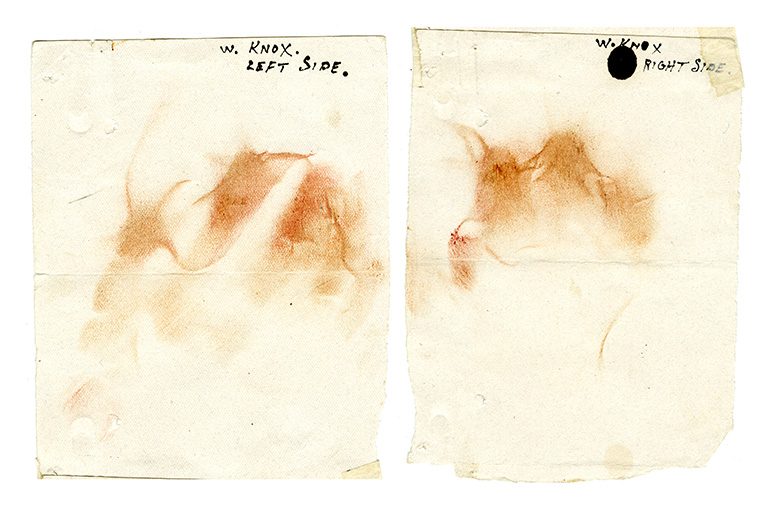

And of course, in 1936 sexual acts between men in public and in private were illegal. Which meant that, for police, the logic went that: ‘the man who owned a powder puff was effeminate; the effeminate man possessed illicit sexual desires; and that such a man was, in police jargon, of the ‘male importuning type’[1]. For queer men, every space they occupied – at home, in the pub, at work – could be subjected to scrutiny by the state. And as it was difficult to witness or obtain evidence to prove importuning or soliciting, or prosecute a venue under the ‘Disorderly Houses Act’, officers looked for things they felt signified the likelihood to undertake same-sex sexual acts: particular gestures, comments, items of clothing or products. The desire to obtain physical evidence was also enhanced by pressure on the Metropolitan Police to prevent wrongful accusations, after a number of high profile court cases where men were accused of importunity based on uncorroborated testimonies. We can see the evidence of this on a piece of blotting paper smeared with make-up that now sits in The National Archives’ collection, taken from the face of 44 year old waiter William Knox. William was arrested in Piccadilly for soliciting men in the street – his face ‘highly coloured and his lips red,’ according to the officer – and sentenced to two years’ imprisonment.

Make-up traces collected by police, 1938 (catalogue reference: CRIM 1/1041)

There are cases in the files where men accused of carrying or wearing make-up state that they had it with them for distinct reasons. In his testimony following the raid on Billie’s, Ronald admits he did have powder on his face: talcum powder, which he applied that night after he’d had a shave. In ‘The Man with the Powderpuff’, Matt Houlbrook shows how there are multiple cases throughout the 1920s and 30s where men caught wearing make-up argue against the police’s assumptions: from West End theatre performers still wearing the remnants of a day’s work on the stage, through to a young man who’d been carrying the contents of his mother’s purse after the handle broke – and even a dark-skinned waiter who’d been told to lighten his complexion by his employers.

The unwillingness to explore the logic of connecting cosmetics to a prosecution for same-sex sexual acts may in part have come from a desire to limit all visible gender transgression in London: established gender roles had been broken and remodelled to accommodate new circumstances brought about by the first world war, with women adopting work roles previously filled by men, and many men returning altered – both physically and mentally. This fear of gender transgression is evident in the words of the inspector who instructed the officers to undertake the raid at Billie’s on the 14 November. He wrote in the report: ‘It was really a sickening sight to see these men adopting an effeminate posture and it is to be hoped that we can at least make an example of some of them though this prosecution and thereby allay the spreading of this social cancer.’

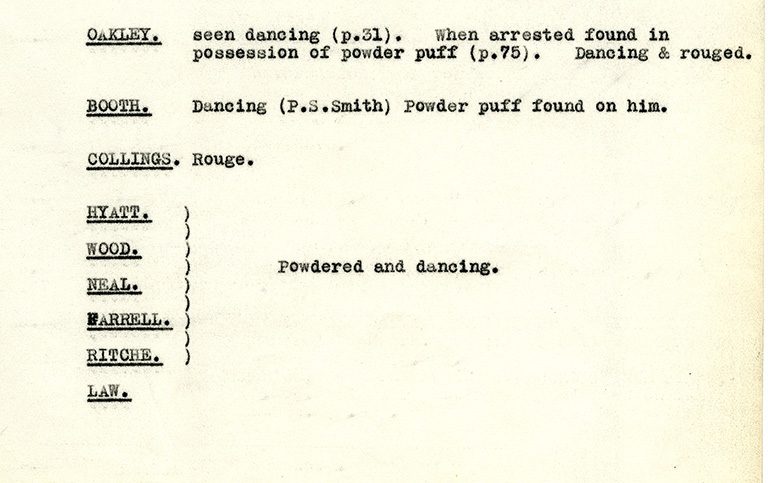

Roughly 35 people were accused of aiding and abetting Billie Joyce in running a ‘disorderly house’ on the night of 14 November. Twenty were found guilty. Billie, 31 at the time of the hearing, was sentenced to two years in prison, along with her colleagues James and ‘Connie’ (Ivy Connie Locke). Arthur, accused of ‘dancing indecently’ with William Hibbert as well as ‘indecent language,’ was sentenced to six months in prison. Ronald, who had been seen indecently dancing, kissing, and sitting on Frederick Branch, was also sentenced to six months in prison. Fifteen were not prosecuted, six of whom had no more evidence against them other than the accusation that they had been seen ‘powdered and dancing’.

A document summarising the evidence against the members of Billie’s club (catalogue reference: DPP 2/355)

Documents

- The National Archives: Director of Public Prosecutions case papers: Billie’s Club, 1936 (DPP 2/355)

- The National Archives: Central Criminal Court Depositions: Joyce, Billie; Locke, Ivy and 34 others. Keeping a disorderly house, 12 Jan 1937 (CRIM 1/903)

- The National Archives: Defendant: KNOX, William. Charge: Importuning for immoral purposes, 1938 (CRIM 1/1041)

Further reading

- Sasha Archibald, ‘Making up Hollywood’, Cabinet Magazine, 2013

- Mick Brown, ‘Denmark Street: the threatened birthplace of the British record industry’, The Telegraph, 2015

- Juliette Edwards, ‘Powder Compacts: A Collector’s Guide’, 2000

- Jane Hamlett, Hannah Greig, Leonie Hannan, ‘Gender and Material Culture in Britain since 1600’, 2015

- (1) Matt Houlbrook, ‘The Man with the Powderpuff in Interwar London’, 2007

- Matt Houlbrook, ‘Queer London: Perils and Pleasures of the Sexual Metropolis, 1918-1957’, 2005

- Jennifer Lee, ‘Big Tobacco’s Spin on Women’s Liberation’, New York Times, 2008

- Daily Mail, ‘Billie Joyce Weeps at 2-Year Sentence’, pg 7, issue 12717, 1937

- Florence Tamagne, ‘A History of Homosexuality in Europe Vol. I: Berlin, London, Paris, 1919-1939’, 2004

- Jeffrey Weeks, ‘Between the Acts: Lives of Homosexual Men, 1885-1967’, 1990

Fascinating but tragic. I would love to know how Billie’s life turned out after two years in jail for hosting a party in a club …

Fascinating stuff, thank you for this