I have been working with The National Archives as part of my Public History MA at the University of York. My project involved producing a prototype board game, based on a historical event or period. In the end, the game took the form of a journey, more specifically pilgrimage during the Crusade period – called ‘Pilgrim’, for lack of a more imaginative title. Although, the end goal of the prototype game is reaching Jerusalem first, I wanted to focus more on the journey itself and the possible events that could happen: especially to show that, during the Middle Ages, such a task was quite a dangerous one. The benefit of using a game structure to present this narrative of history is that the individual characters and events can inspire the imagination: you can feel more involved, playing as if you were one of them.

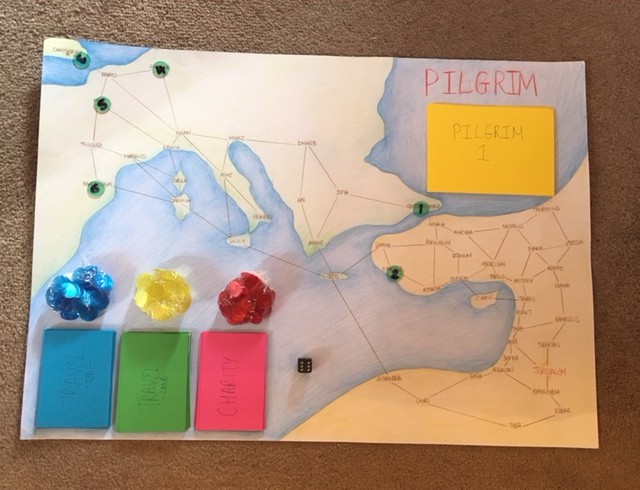

Pilgrim prototype (version 2)

Throughout this project I have learned that, to be a gameful designer, you must identify the challenges which can fulfill the players needs: in other words, giving rewards.[ref]Sebastian Deterding, ‘The Lens of Intrinsic Skill Atoms: A Method for Gameful Design’, in Human-Computer Interaction 30, 3-4, (2015): 304.[/ref] The iterative process, generating outcomes towards a desired goal, shares similarities with historical scholarship.[ref] Dawn Spring, ‘Gaming history: computer and videogames as historical scholarship’, in Rethinking History 19, 2, (2015): 208.[/ref] The process should be grounded in historical objectives and, although it must convey a relevant historical narrative, the gameplay is still at the centre of the design process.[ref]Spring, ‘Gaming history’, 215.[/ref] This idea is complex; as a historian, you wish to put historical fact before game mechanics. However, historians are not so much collectors or producers of facts – they are more organisers of them, relating them in a narrative style to find meaning.[ref]Roland Barthes, ‘The Discourse of History, section II’, in The postmodern history reader, ed. Keith Jenkins, London: Routledge, 1997, 121.[/ref] Which appears to be the same as organising the facts into a game style to find meaning through play.

From the outset, it became a goal of the project to include a wider range of perspectives: the final characters included a heretic, a Byzantium priest, a woman pilgrim, a crusading knight, a Hospitaller and a Muslim merchant. Each character has their own card outlining who they are, where they are from and the purpose of their pilgrimage. The idea for collaboration came to fruition in the game design document, to employ some variation with the opportunity to cooperate and interact with other players, taking shape through the events. Examples of negative events include ambush and death: pilgrims could find themselves among hostile locals, like real Norman pilgrims who were robbed or murdered by Italian peasants.[ref]Jonathan Sumption, Pilgrimage: an image of mediaeval religion, London: Faber, 1975, 118.[/ref] Hazardous events were only exemplified on the longer and treacherous journey to Jerusalem.[ref]Sumption, Pilgrimage: an image of mediaeval religion, 182.[/ref] Positive events included the collection of relics that could be distributed to friends and benefactors to signify the blessing that had been acquired.[ref]Diana Webb, Pilgrims and pilgrimage in the medieval West, London: I.B Tauris Publishers, 1999, 26.[/ref] These events turned into ‘event cards’, which would be selected once a travel action had been performed, or ‘charity cards’, which could be selected instead. Instead of charity card benefiting your own character, it solely benefits another, resulting in a mechanism for cooperation.

Representing progress was an issue that frequently appeared during the design process. Progress did not necessarily have to equate to distance. But when working with a map layout, distance defines movement – so that was a tricky theory to overcome, a problem which needed further exploration when considering the future changes that could be made. To add another dimension to the game, there needed to be something changeable and yet also different for each character. Religion is commonly used in fantasy games, as it allows a moving force of change: it can be used as a primary resource to gain power or achieve goals.[ref]Ryan Clarke Thames, ‘Religion as Resource in Videogames’, in Online-Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 5, (2014): 183/4.[/ref] I decided to use individual resources to represent religion or piety, health and wealth: the mechanic was ‘Pool Building’, where you start with set resources and during play these can either increase or decrease. These resources or player stats are changeable depending on which event cards you select. To find a relationship between value and motivation,[ref]Jesse Schell, The Art of Gaming: a book of lenses, Taylor & Francis Ltd, 2008, 32.[/ref] they also help to show the player what is important, making them actively engage in the events and how they affected the journey. Hopefully this sees a translation of mechanical questions into historical questions.[ref]Spring, ‘Gaming History’, 217.[/ref]

Pilgrim prototype (version 1)

You can never know how a game will pan out until it has been tested with real people. I certainly found this to be true; what was written in the design document did not exactly translate into the material form. From both play tests, with students and then heritage professionals, the game was enjoyed and there was some potential within it to learn about pilgrimage during the Middle Ages. The layout of the board proved to be one of the most difficult things to consider. The first draft of the board saw that each player had their own map all leading to the centre, Jerusalem. I thought this would solve the problem of equally spacing each character from the end goal and more spaces could be added if necessary. For example, the sinner starts in Canterbury, whereas the merchant starts in Edessa. I soon found that this structure did not allow the players to interact and acts of charity seemed unrealistic when players were not near. Also, it did not allow enough choice and the one path resulted in players reaching the goal too quickly. As a result, the second draft of the game was very different: I decided that all the players must navigate the same board; town and countryside changed to land and sea. Sea travel adds new possible dangers such as the likelihood of pirates.

The feedback from testing at The National Archives suggested that it would be interesting to further explore the idea of strategy in the game by giving the characters secret motivations that linked to their individual qualities. This would also make the game more historically accurate, as people have many different motivations for going on a pilgrimage not just for religious purposes. As with play testing, ‘new questions arise that may require completely different paths’.[ref]Spring, ‘Gaming history’, 218.[/ref] The work of game designers and historians is different, but they still use the same iterative processes.

If there had been more time to continue to test and improve the game, there are certainly changes that could be made to enhance its historical significance. As the game stands, Jerusalem is still the end goal – albeit a not-necessarily historically accurate end goal. Not everyone who went on a pilgrimage during the Crusades made it to Jerusalem, or even had intentions of reaching that destination. To combat this, adding another way to win may reflect the differing motives that pilgrims had. Religious shrines and relics featured heavily in the traditional journey. Therefore, I would have created a way for players to collect relics at sites where significant medieval shrines had been, to offer an alternative way of winning. Ideally this would create a better balance between the historical significance and playability. This is crucial when trying to make a ludic historical game.

Looks like a great game and it’s appreciated how you thought about the process as well as the end goal. Would love to play

That was a totally fascinating read – so interesting to hear about the process and the game sounds amazing – I would absolutely want to play it!

I think my family would enjoy playing this game over weekend!