Peter Vannes (c.1488-1563) was a diplomat and collector of papal taxes in England under four successive Tudor monarchs: Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I.

Vannes first arrived in England from Italy in 1513 and by the following year he was working for Cardinal Wolsey. His career began in earnest in 1527 when he visited the pope with Wolsey, working alongside him as a key figure in the divorce negotiations between Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. [ref]1. L. E. Hunt, ‘Vannes, Peter (c.1488–1563)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/28097, accessed 5 Dec 2016[/ref]

Three documents in the E135 series, which I have been cataloguing as part of my PhD placement, relate directly to Vannes. While Peter Vannes was central to divorce negotiations on behalf of the king, in these documents he allows for other marriages to go ahead.

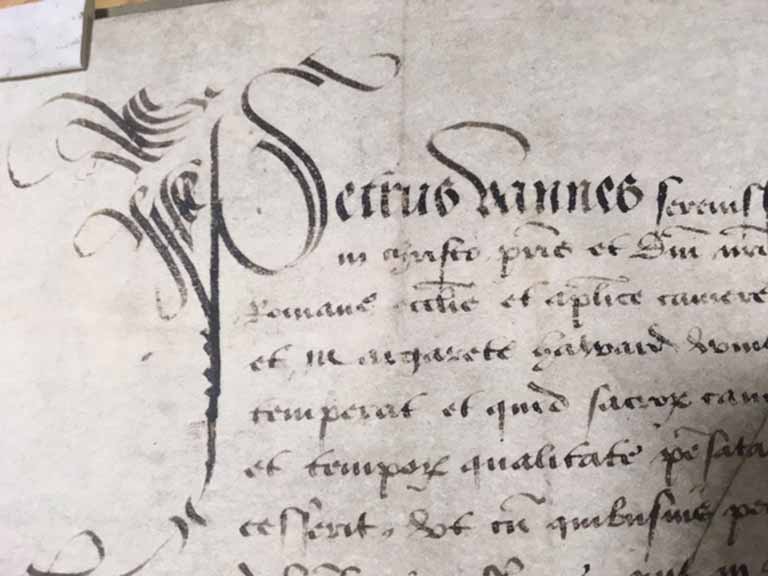

The first document dates from 1530 and is for the marriage of Sir Thomas Arundell, Justice of the Peace for Cornwall and administrator under Henry VIII and Edward VI, and Margaret Howard, who was the sister of Katherine Howard, Henry VIII’s ill-fated fifth wife (E135/7/25).

Document for the marriage of Sir Thomas Arundell and Margaret Howard (catalogue reference: E135/7/25)

The couple appear to have had a much more successful marriage than Henry and his fifth wife. They had two sons and three daughters and remained married until Arundell’s death in 1552, when he was executed on suspicion of conspiracy against the Crown.[ref]2. Pamela Y. Stanton, ‘Arundell, Sir Thomas (c.1502–1552)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2009, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/725, accessed 5 December 2016[/ref]

The seal of Peter Vannes’ office (catalogue reference: E135/7/27)

The next document in which Peter Vannes features contains a perfect example of the seal of his office (E135/7/27). The seal here is important because it authenticates the document allowing the marriage to go ahead and demonstrates the power of his position.

This seal shows St. Peter and St. Paul standing opposite each other under an arch with an image of Christ on the cross between them. Below the crucified Christ is a lectern, on which there is the image of two keys, representing the keys to heaven. The inscription Sigillum Collectorie Camerae Apostolice in Regno Angliae can be seen around the outer edge of the seal. Other examples of seals very similar to this can be seen in E30/1012 and E30/1451.

In this document Vannes is giving permission for the marriage of Thomas Skevington and Anne Asheby, who were cousins. Dispensation was needed for this marriage because of the issues of consanguinity and affinity: this meant that if you were related to another individual, spiritually or by blood, through a certain number of degrees, you couldn’t marry. To work this out, you needed to count down the line of descendants from the same common relative; if this took four steps or fewer the couple could not be married without special permission.[ref]3. See R. H. Helmholz, Marriage and Litigation in Medieval England (Cambridge, 1974), 78[/ref]

The third and final document relating to Vannes in this series is a dispensation that was actually granted by his deputy, Richard Gwent. This was for another marriage for two people related in the fourth degree, Thomas Barton and Maud Redmayn (E135/7/28).

These two dispensations date from 1533 – the same year that Henry VIII married his second wife, Anne Boleyn. Interestingly, for his divorce from Catherine of Aragon, Henry claimed that under the ruling of consanguinity and affinity their marriage was invalid: Catherine had been married to his brother, Arthur. The fact that Vannes issued these dispensations to get around the sticky issue for other would-be spouses seems somewhat ironic when viewed in this light.

Vannes did manage to survive Wolsey’s fall from grace and went on to become Henry VIII’s Latin Secretary in 1528 and then collector of papal taxes in England in 1533, following a personal recommendation from the pope.[ref]4. SP1/51 f.9[/ref]

He died between 28 March and 1 May 1563, leaving behind two wills, the first of which was granted on 21 May 1563 and survives at The National Archives (PROB11/46/223). The main heir to Vannes’ estate was ‘Benedict Hudson, alias Vannes’ who was probably his illegitimate son.[ref] 5. Ibid; Prob 11/46/223[/ref]

The E135 series has shed light on Vannes’ career and his fascinating role in marital negotiations after his involvement in Henry VIII’s divorce. This is another fascinating example of the unexpected stories that can be uncovered in the archives.