‘A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.’ Or would it? In 1933, the Persians asked governments around the world to make slight adjustments to the way in which they referred to their country and ruler. In 1934, they informed foreigners that from 21 March 1935 Persia should be officially called Iran.

This may sound like reasonable requests given the Persians (or Iranians, as they were to be called) had been calling their country this for, well, ever. The Foreign Office, however, didn’t see it that way.

On 1 December 1933 the Oriental Secretary in Tehran, Trott, sent a memo on the change of titles requested by the Persians, and its importance. The Persians, he explained, wanted their country to be referred to as the Imperial Persian State and their ruler, the Shah, to be acknowledged as Sháhinsháh (King of Kings), a title used since Antiquity. ‘It is arguable,’ he wrote, ‘that the Persians are entitled to decide for themselves what their State and their Government should be called.’

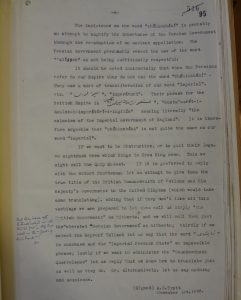

However, he continued, the British Government had never used these names in the past, and it was clear it was merely ‘an attempt to magnify the importance of the Persian Government through the re-adoption of an ancient appellation’ (FO 371/17890).

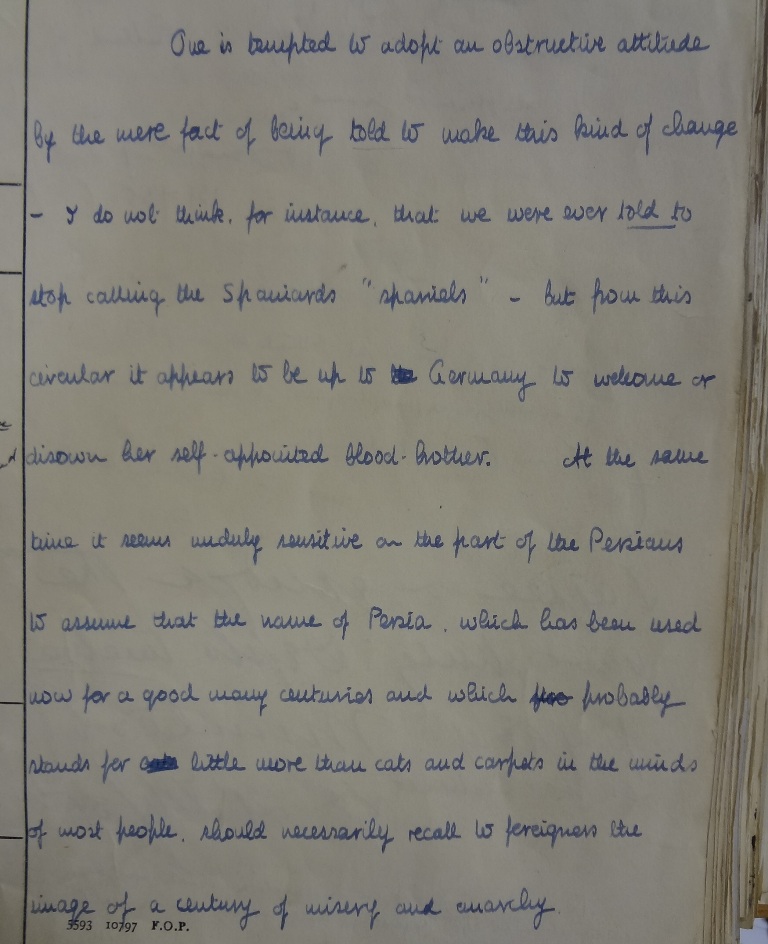

- Trott’s memorandum, 1 December 1933 (catalogue reference: FO 371/17890)

- Trott’s memorandum, 1 December 1933 (catalogue reference: FO 371/17890)

- Trott’s memorandum, 1 December 1933 (catalogue reference: FO 371/17890)

- Trott’s memorandum, 1 December 1933 (catalogue reference: FO 371/17890)

Trott suggested the Foreign Office had four options. The ‘Quip Modest’ (‘which kings is Reza King over?’), the ‘Retort Courteous’ (‘give them the true title of the British Commonwealth of Nations’), the ‘Countercheck Quarrelsome’ (‘we know how to translate as well as they do’), or plain acceptance.

The Foreign Office thought the matter was rather silly and noted: ‘it would surely be flattering the Persians unduly to intimate that H.M.G. have given a moment’s thought to their real or imaginary titles (…). If the phrase ‘the King of Kingly Persian Government’ is nonsense, so much the better’ (FO 371/17890). The Eastern Department agreed that the only sensible thing to do was to accept the Persian request. That seemed to be it.

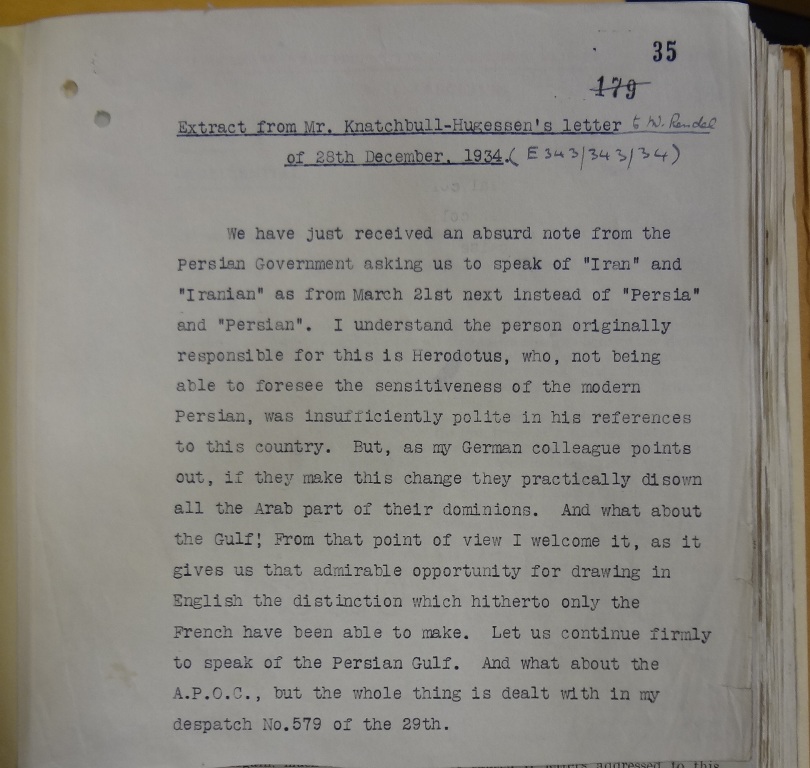

It all started again almost exactly a year later. On 28 December 1934, the British Minister in Tehran, Knatchbull-Hugessen, wrote to George Rendel, the Head of the Eastern Department. ‘We have just received an absurd note from the Persian Government,’ he complained, ‘asking us to speak of “Iran” and “Iranian” as from March 21st next instead of “Persian” and “Persians”’ (FO 371/18988).

The Persian Ministry for Foreign Affairs had indeed circulated a note explaining they merely wished to correct an ‘etymological and historical inexactitude’. It was only, according to them, an issue of mis-translation based on the word used by Greek historians. This prompted Knatchbull-Hugessen to write to Rendel:

‘I understand the person originally responsible for this is Herodotus, who, not being able to foresee the sensitiveness of the modern Persian, was insufficiently polite in his references to this country’ (FO 371/18988).

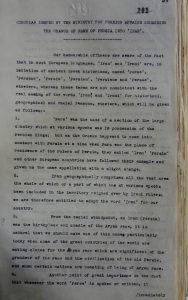

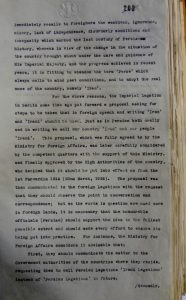

The reasons behind the change were slightly more complicated. First, the Persians felt that ‘as the birthplace and cradle of the Aryan race’, they should ‘make use of this name’, especially as ‘some of the great countries of the world [were] making claims for the Aryan race’. You probably won’t be surprised to hear this had been suggested by the rather Nazi-friendly Persian ambassador in Berlin. Secondly, they thought that the name of Persia conjured up terrible images in the minds of foreigners. They wrote:

‘Whenever the word ‘Perse’ is spoken or written, it immediately recalls to foreigners the weakness, ignorance, misery, lack of independence, disorderly condition and incapacity which marked the last century of Persian history’ (FO 371/18988).

The change was therefore also meant to emphasise all the good changes that had taken place since Reza Shah Pahlavi had come into power in 1925.

- Extracts from the circular issued by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs regarding the change of name of Persia to Iran (catalogue reference: FO 371/18988)

- Extracts from the circular issued by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs regarding the change of name of Persia to Iran (catalogue reference: FO 371/18988)

The Foreign Office was not impressed. The Eastern Department, in particular, thought it was ‘a piece of pedantry’ and that it was going to cause a lot of practical problems. Andrew Lambert wrote:

‘It seems unduly sensitive of the Persians to assume that the name of Persia, which has been used for a good many centuries and which probably stands for little more than cats and carpets in the mind of most people, should necessarily recall to foreigners the image of a century of misery and anarchy’ (FO 371/18988).

Lambert was being somewhat flippant, but more serious issues were raised. Changing Persia into Iran in all official names and correspondence meant changing the name of companies (notably the Anglo-Persian Oil Company and the Imperial Bank of Persia), and potentially that of the Persian Gulf (with the danger of Persia claiming ownership); it also meant modifying maps, including military maps and surveys; the general public also had to be informed, so that letters sent to Persia could be delivered. Finally, the Foreign Office feared Iran may be confused with the relatively new state of Iraq.

The Persian Minister in London, Hussein ‘Ala, took to the press to defend the change, and wrote to the Editor of the Times on 29 January 1935:

‘What we are doing is simply to ask others to speak and write of us by our real name, by the name we have always used ourselves (…). We want to remove the anomaly of a country being known by foreigners as Persia when it really is called Irân’ (FO 371/18988).

The argument seemed a bit flimsy, given most countries are called something different in each language; Knatchbull-Hugessen pointed out that the Persians themselves called Greece ‘Yunnan’ instead of ‘Hellas’ and Poland ‘Lohistan’, not ‘Polska’. The Eastern Department commented: ‘we might take the opportunity of asking in return to be called “Britannia Kabir” instead of “Inglistan” in all official correspondence.’

In the end, the Foreign Office recognized there was really nothing much they could do. Once they were reassured that the Persian Gulf wasn’t about to become the Iranian Gulf, it was decided the public should be advised to address their letters to Iran, and that the companies could choose for themselves (they all changed their names). This time, surely, that was it.

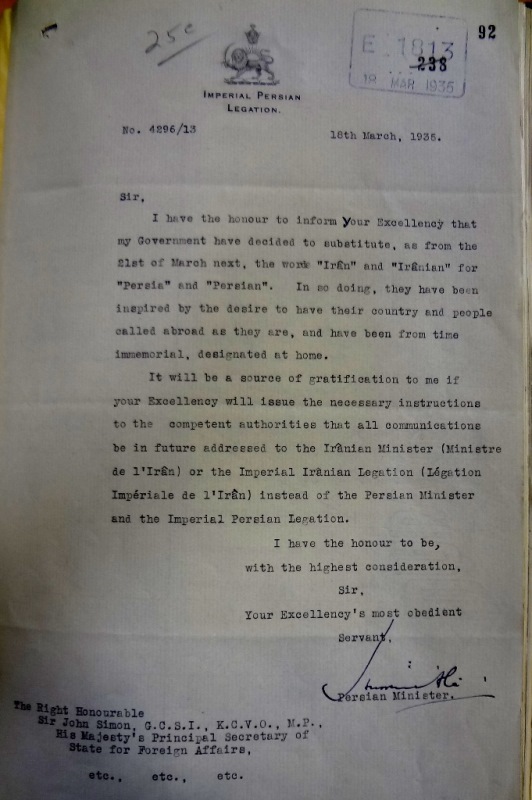

Hussein ‘Ala to John Simon, 18 March 1935 (catalogue reference: FO 371/18988)

On 18 March 1935, as everyone was slowly getting used to the idea that Persia was about to disappear from the maps, the Persian Minister in London wrote to the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, John Simon, to remind him of the 21 March deadline:

‘It will be a source of gratification to me if your Excellency will issue the necessary instructions to the competent authorities that all communications be in future addressed to the Irânian Minister (Ministre de l’Irân) or the Imperial Irânian Legation (Légation Impériale de l’Irân)’ (FO 371/18988).

This started the Battle of the Circumflex.

The Foreign Office reacted slightly more forcefully than you would expect. ‘I think it is fairly clear’, Lambert wrote, ‘that we cannot use the circumflex accent – it looks even worse in French than in English’.

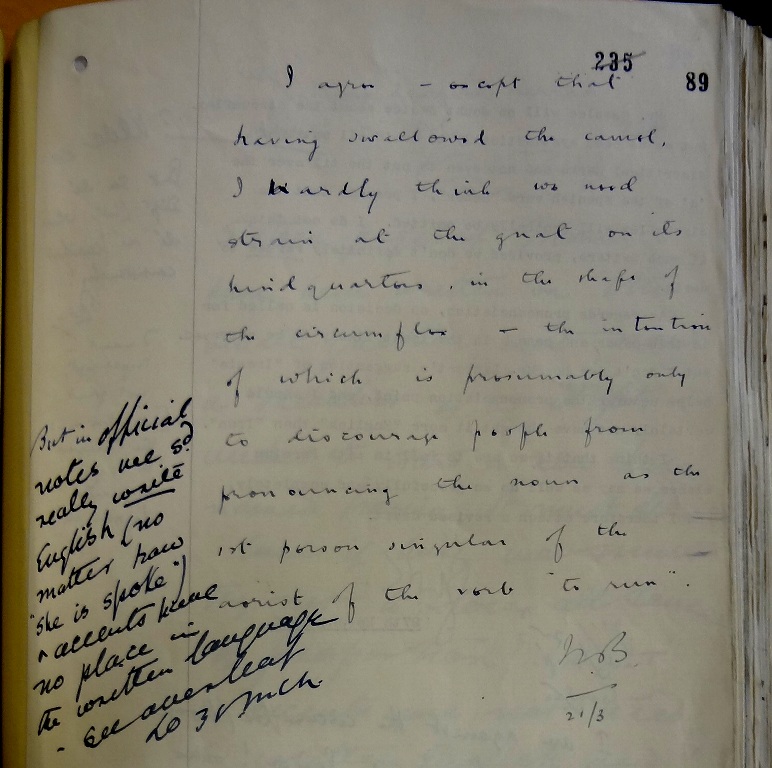

Lancelot Oliphant, an undersecretary of State for Foreign Affairs, agreed that accents had ‘no place in the written language’. One of their colleagues pointed out that it was a relatively minor and rather silly issue, with the floweriness and pedantry we’ve all come to cherish in Foreign Office minutes:

‘Having swallowed the camel I hardly think we need strain at the gnat on its hindquarters, in the shape of the circumflex – the intention of which is presumably only to discourage people from pronouncing the noun as the 1st person singular of the aorist of the verb ‘to run’’ (FO 371/18988).

They turned to the Foreign Office Librarian, Stephen Gaselee. Gaselee didn’t like diacritic marks much (except, for some reason, the tilde on Señor) and was strongly opposed to the circumflex. He also recalled that, sometimes, the spelling rules imposed by others were not that important; after all, the Foreign Office wrote ‘Iraq’, ‘against the more slightly correct, beloved-by-the-Colonial-Office, ‘Irāq’. But this was an entirely different battle.

Lambert then noted he wasn’t entirely satisfied with the pronunciation of Iran, circumflex or not. He was in favour of ‘Irania’ over ‘Iran’ because it was ‘at once more English and more harmonious’.

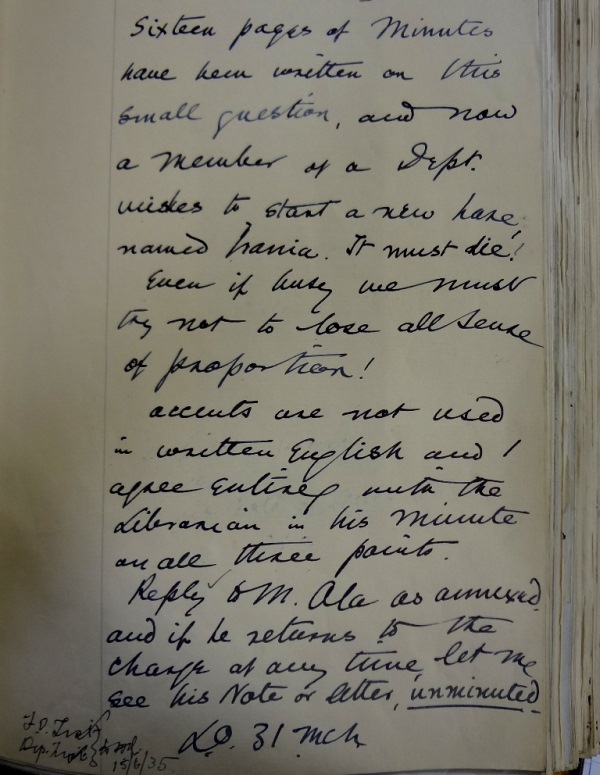

We can hardly blame Lancelot Oliphant for being slightly irritated by the whole thing… ‘Sixteen pages of minutes have been written on this small question’, he raged, ‘and now a member of a Department wishes to start a new haze named Irania. It must die!’ (FO 371/18988).

So it did die. And so did the circumflex. Persia became Iran (except in Foreign Office indexes, where it remained Persia), and the matter was gradually forgotten.

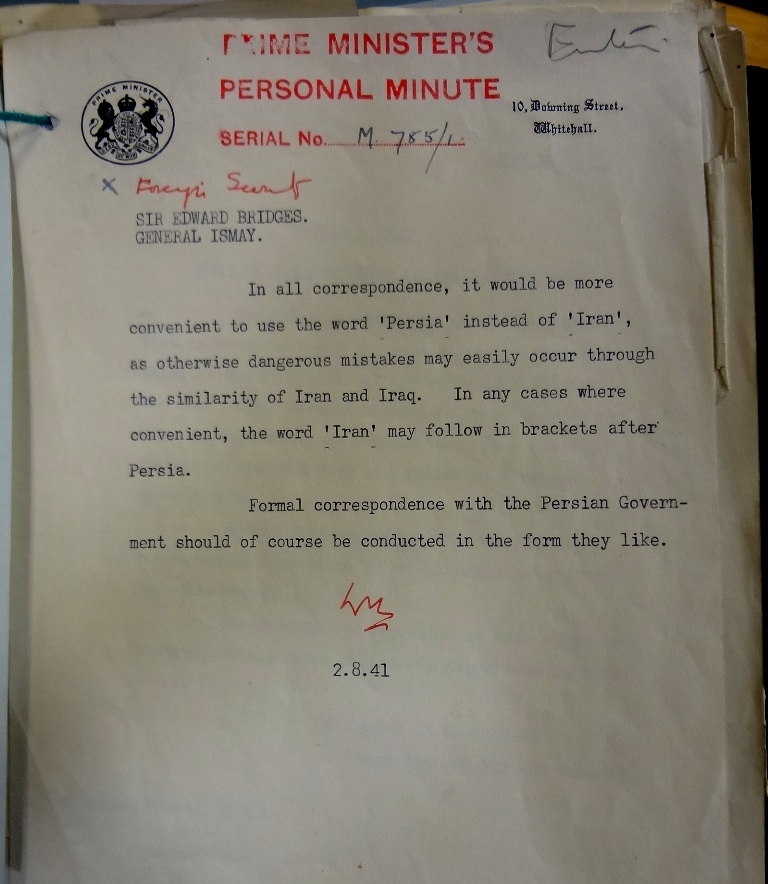

It was resurrected during the Second World War, by Churchill himself. On 18 January 1941, he sent a minute to Anthony Eden, then Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, demanding to know why Persia was called Iran. Having been told the whole story, the Prime Minister concluded that

‘in all correspondence it would be more convenient to use the word ‘Persia’ instead of ‘Iran’, as otherwise dangerous mistakes may easily occur through the similarity of Iran and Iraq (…). Formal correspondence with the Persian Government should of course be conducted in the form they like’ (FO 370/642).

I other words, Persia was to be used internally and Iran externally, as well as in official publications such as treaties or white papers. The Foreign Office noted: ‘This is the wildest nonsense’.

In June 1942, Eden was asked to explain in Parliament whether Persia or Iran should be used. The question wasn’t entirely devoid of importance. As the Head of the Permanent Committee for Geographical Names pointed out, the Army and the Navy had to be provided with maps ‘which would be understood in those countries and through oral contact’. Eden replied: ‘it’s been our habit to call foreigners any name we like’ (FO 370/691).

The issue was raised again in December 1951, when a white paper referred to Persia rather than Iran. Furlonge, the head of the Eastern Department, justified the choice of name by saying he had ‘a strong impression that sometime after 1942, the Persians relaxed the ban on the use of “Persia”’, but admitted he couldn’t trace any actual papers on the subject (FO 370/2108).

I have been equally unable to trace papers in Foreign Office records, but the Chancery in Tehran reported in January 1952 that ‘the Shah had agreed to accept the use of the words “Persia” and “Perse” as a designation for Iran in foreign languages (…) but not by Persians when speaking a foreign language’ (FO 370/2202). In other words, the Foreign Office could call Iran whatever they liked. And it was Persia, until at least 1959, when the registry system recorded correspondence under ‘Iran’ for the first time.

As the Foreign Office noted in 1935, ‘in the end, a country can presumably choose the name it wishes to be addressed by officially’, and change its mind as often as it wants (FO 371/18988). But at least, in 1952, confirmation was given that it should be safe enough to speak of the Shah of Iran but stroke Persian cats, on Persian rugs.

What a fascinating article!

This is of course not an isolated example, why use Holland when it has been for very long time ‘The Netherlands’ (Arnhem is not in the old Provinces of Holland) and of course there is the area of Holland in Lincolnshire, the fact is that Government records still record The Netherlands as Holland. The point raised by the Foreign Office about the APOC (Anglo-Persian Oil Company later the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company) is a valid point. The question of Germany (which only became the German Empire in 1871) and not, for example, Prussia. Of course this country should, in theory, be referred to as The United Kingdom of the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland’ and not just as ‘England’ as it often is (for example soldiers report that they are returning to ‘England’).