One third of a pound does not go far today – it’s not even a small child’s pocket money. But in 1603, it helped Shakespeare secure his future.

Six shillings and eight pence is what Shakespeare’s company of actors, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, were charged for the first stage of a bureaucratic process to gain a licence granting them the patronage of the new king, James I; henceforth, the company would be known as the King’s Men. It was expensive – at the time, actors in London were normally paid less than one shilling a day – but it was to prove a wise investment.

This information has recently come to light in a new examination of a document in The National Archives by Dr Hannah Crummé.

On 24 March 1603 James VI of Scotland succeeded his cousin, Elizabeth I, as James I of England; on 5 April he left his homeland to secure his new kingdom.

In one of his very first acts he granted a licence[ref]1. This licence was in the form of a legal document known as a letters patent, issued under the great seal of the realm[/ref] allowing Shakespeare’s company to perform comedies, tragedies, and other stage plays at its usual home the Globe Theatre in London, at the royal court, and in all towns and universities for ‘the recreation of our loving subjects’.

But before this could happen several interim drafts and instruments known as warrants or bills had to be drawn up by a series of government departments – the Signet Office, the Privy Seal Office, and the Chancery. Each charged its own fees for use of its own distinctive seal; 6s 8d was only the first round of payments.

The paper trail recording the creation of James I’s licence to Shakespeare and his fellow actors has long been known and the documents can be viewed online. However, the search had not been taken back to the first stage of the process – the Signet Office itself – until now, very probably because the entry to the licence had not been indexed at the time under Shakespeare’s name. The cost of the first part of this almost tortuous administrative procedure was previously unknown.

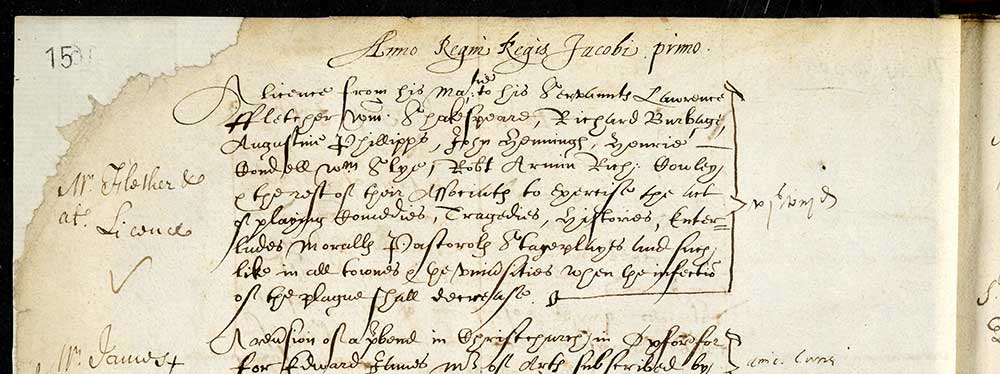

The 6s 8d is listed in a docquet book, or register of fees, collected by the clerks of the Signet Office (SO 3/2).

Summary in Signet Office’s docquet book of licence to the Lord Chamberlain’s Men and fee charged (catalogue reference: SO 3/2)

Judging from other entries, this amount appears to be the standard rate charged to authorise and process initial drafts of such grants and privileges. Further fees had to be paid again in the Privy Seal Office and Chancery. After the licence was given to them, the company had it enrolled – in other words, an official copy made and kept by central government.[ref] 2. The enrolled copy of the licence is currently on display in the Keeper’s Gallery.[/ref] This was not legally necessary and again came at a cost.

The speed at which all this happened – the licence was issued on 19 May, within a fortnight of the king reaching London – is reflected in the fact that the Signet Bill sent by the Signet Office to the Privy Seal Office carried an early, incorrect version of the Signet Office’s new seal.

James was keen to be seen as king of a new ‘empire’ – a bigger and better Great Britain – and had instructed his new principal secretary, Robert Cecil to engrave a new seal with the arms of both his kingdoms for such administrative purposes. Cecil had done so, adding Scotland to the existing royal arms which until then had borne only the arms of England and France. But he had not realised that James also wanted to incorporate the harp of his fourth kingdom, Ireland; the omission was quickly rectified, but too late for Shakespeare’s Signet Bill.

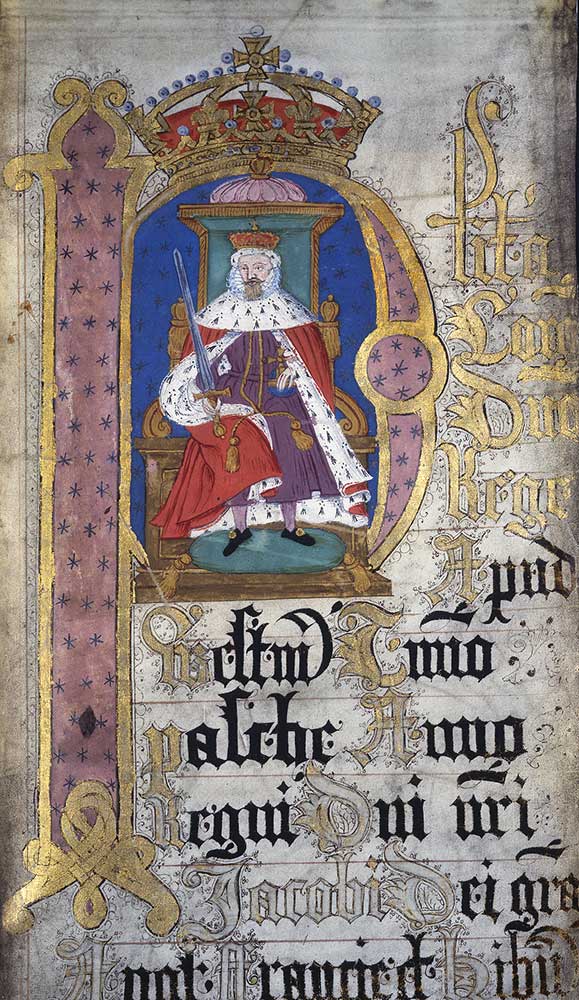

Moreover, even the final licence (which no longer exists) given to Shakespeare’s company would have had to bear the superb second great seal of the old queen as James’ new great seal was not yet ready.

Second Great Seal of Elizabeth I (catalogue reference: SC 13/N3)

The fees charged proved to be a sound investment for the ambitious 40 year old Shakespeare and his fellow actors. [ref]3. Lawrence Fletcher (actor known to James in Scotland), William Shakespeare, Richard Burbage (a leading actor), Augustine Phillips (actor), John Heminges (actor and manager), Henry Condell (actor), William Sly, Robert Armyn (witty actor), Richard Cowley (actor).[/ref] It secured them the right to play at the royal court, where they were soon established as the chief entertainers: they were to perform at least 107 times before the Shakespeare’s death in 1616. They were also to become the pre-eminent acting group touring the country, especially valuable while the Globe was closed for the next year because of the plague. Moreover, the company clearly had the ear of the new king very probably thanks to one of its actors, Lawrence Fletcher, who accompanied James down from Scotland.

Shakespeare himself had risen socially: he was now officially a gentleman with his own coat of arms. He was also a successful actor, playwright and poet, and he had recently bought a splendid new house, New Place, in his old home town of Stratford Upon Avon.

James was fascinated by literature, and bestowed favours to all and sundry of his new ‘loving subjects’ who were obviously keen on the theatre: over a third of London’s adult population were viewing a play every month.

As this new document proves, Shakespeare was not slow to follow Brutus’s advice in ‘Julius Caesar’, taking the tide of his own affairs when at a flood, which, of course, was to lead on to fortune.

Most interesting; certainly one for my grandson who is really into history.

Thank you Dr Ailes! I think I met you in the map room once! And many congratulations to Dr Crummé on such an exciting discovery. I’ve just discovered the TNA blogs myself and have been up half the night reading them. Fascinating stuff!