If you’ve ever been to Paris, you may, as most people do, have missed the bullet holes on the façades. Yet they are the physical remnants of the August 1944 Parisian insurrection, a constant reminder that, on 25 August 1944, after four years of German occupation, Paris was finally liberated.

Paris, of course, isn’t France (despite what any good Parisian would tell you), but even the Germans knew it: ‘history shows that the loss of Paris has always meant the loss of France’. Yet, Paris was not a strategic target for the Allies, whose plan was to bypass the capital. It would take the courage and determination, some would say obstinacy, of a long list of people and acronyms to make them change their mind: General de Gaulle, General Leclerc, Captain Dronne, Colonel de Langlade, Colonel Billotte, Colonel Rol-Tanguy, Captain Gallois, General Chaban-Delmas, Georges Bidault, Alexandre Parodi, the FFI (Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur, the armed wing of the Resistance), the CNR (Conseil National de la Résistance, the Resistance leaders), the CPL (comité parisien de liberation, the Paris liberation committee), the COMAC (comité d’action militaire, the Resistance’s military committee), and many, many others…

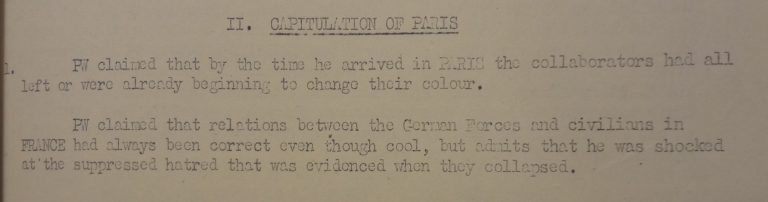

In the summer of 1944, the situation in Paris wasn’t good. General Dietrich von Choltitz, later described by one of his interrogators as ‘a cinema-type German officer, fat, coarse, bemonocled and inflated with a tremendous sense of his own importance’, had been appointed as the military Governor of the Gross Paris on 10 August; the Germans were everywhere and the population, on the verge of starvation, seemed so subdued that von Choltitz admitted, while in custody, that he had been ‘shocked at the suppressed hatred evidenced when they (the Germans) collapsed’.

Yet, the Parisians’ revolutionary spirit had not been totally quashed. It is difficult to determine when the events which eventually led to the liberation of Paris really started. On 14 July with the series of demonstrations that took place on Bastille Day, first clean break with the wait-and-see attitude? On 10 August, when the railway workers went on strike? On 15 August, when the policemen went on strike? It is, of course, an open debate, but I think it is fair to say that the insurrection really started when the Préfecture de Police, the police headquarters, was occupied by policemen in the early hours of 19 August in the name of General de Gaulle and the French Provisional Government. For the first time since June 1940, the Parisians saw the French colours flying over the capital.

This kicked off a full week of fighting. Other official buildings were soon occupied and CNR leader Alexandre Parodi placed the Resistance under the command of FFI Colonel Rol-Tanguy. A truce, negotiated by Swedish Consul Raoul Nordling, was declared in the evening, but fighting continued throughout 20-21 August, mostly because the FFI were convinced that the Germans’ willingness to stop fighting was a proof of weakness.

On 20 August, as they always do when they get really upset, the Parisians dug out cobblestones and set up barricades. These barricades (about 600 in total) were clearly not enough to free Paris, they were too scattered, but they had a strong psychological impact as they were a powerful revolutionary symbol actually involving the Parisians in their own liberation.

Meanwhile, General de Gaulle insisted (some later said demanded) that Eisenhower should send the Free French troops, commanded by General Leclerc, to Paris. He wanted the French to be the first to enter the capital, even though the main decisions were obviously made by the Americans, and he was extremely reluctant to let Paris be liberated by the communist FFI. By all accounts, Eisenhower wasn’t impressed.

On 22 August however, Captain Gallois, sent by Colonel Rol, reached Laval in Brittany. It was the HQ of General Bradley, commanding the US 1st Army. He described the situation very precisely: the threatening starvation, the exhaustion of people, and the lack of ammunition. Order was soon given to General Leclerc and his 2e DB (2nd Armoured Division) to march on to Paris.

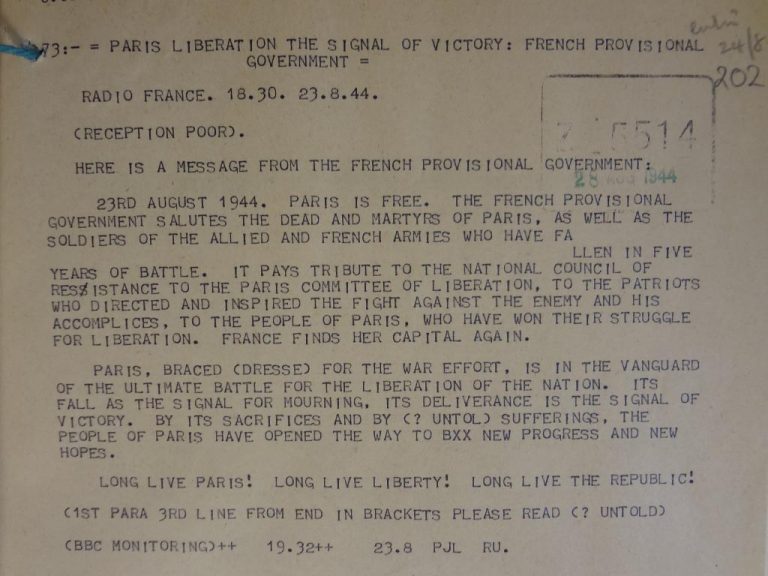

On 23 August at 6.30 pm, the French Provisional Government broadcast a message on Radio France announcing, somewhat prematurely, the arrival of the 2e DB and the liberation of Paris.

Message broadcast by the French Provisional Government on 23 August. (Catalogue reference: FO 371/41863)

On 24 August, General Leclerc sent a small Piper reconnaissance aircraft to Paris, which dropped a message: ‘hold on – we’re coming!’; the Parisians held on. French writer Albert Camus noted in his chronicle: ‘Paris fights today so that France can speak tomorrow’. At 9.22 pm, Captain Raymond Dronne, commanding the 9th Company of Mechanised Infantry, mainly composed of Spanish Republicans and nicknamed ‘la Nueve’, finally reached the Hôtel de Ville, the city hall, which had always been the seat of revolutionary Paris.

On 25 August at 8am, the 4th US Infantry Division entered Paris through the Porte d’Italie, in the south east. Half an hour later Colonel Billotte reached the Préfecture de Police and sent an ultimatum to von Choltitz, giving him 30 minutes to surrender. At about 9.30, General Leclerc entered the city through the Porte d’Orléans, in the south and, guided by Chaban, reached the Gare Montparnasse, where he set up his HQ before leaving for the Préfecture. At 2.30, the Germans from the Majestic Hotel, main HQ of the German troops in Paris, avenue Kléber, surrendered to Colonel de Langlade, who had entered the capital through the Porte de Saint-Cloud (south-east).

At 3pm, Billotte and the FFI took the Meurice Hotel, the Gross Paris Commandant’s HQ, and captured von Choltitz. At 3.30, the German Governor surrendered to General Leclerc. The surrender agreement, on which Rol’s signature also appears, was signed in the name of the Provisional Government, not on behalf of the Allies. From then on, Paris was under de Gaulle’s control.

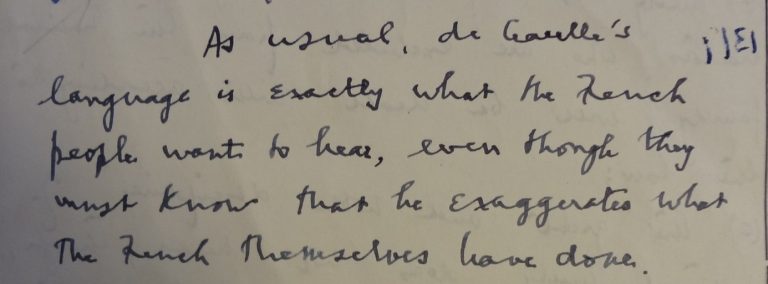

At 7pm, from the Hotel de Ville (the city hall), General de Gaulle delivered that vibrant speech which most French people are still able to recite today: ‘Paris! Paris dishonoured! Paris broken down! Paris tortured! But Paris liberated! Liberated by itself, liberated by its people, with the assistance of the armies of France, with the assistance and support of the whole of France, of fighting France, the only France, the real France, the eternal France.’ The Foreign Office commented: ‘as usual, de Gaulle’s language is exactly what the French people want to hear, even though they must know he exaggerates what the French themselves have done’.

They were probably right. The entry of the Leclerc Division into Paris is as much part of the French nationalist mythology as de Gaulle’s speech and his triumphant military parade from the Arc de Triomphe to Notre-Dame on 26 August, but they couldn’t have done it without the Americans, who supplied weapons and ammunition and, more importantly, made the decisions. They even supplied 15,000 uniforms to the FFI when they were incorporated in the regular army before marching onto Germany. The Americans finally paraded down the Champs-Elysées on 29 August.

American troops parading down the Champs-Elysées on 29 August 1944. (Catalogue reference: FO 898/527)

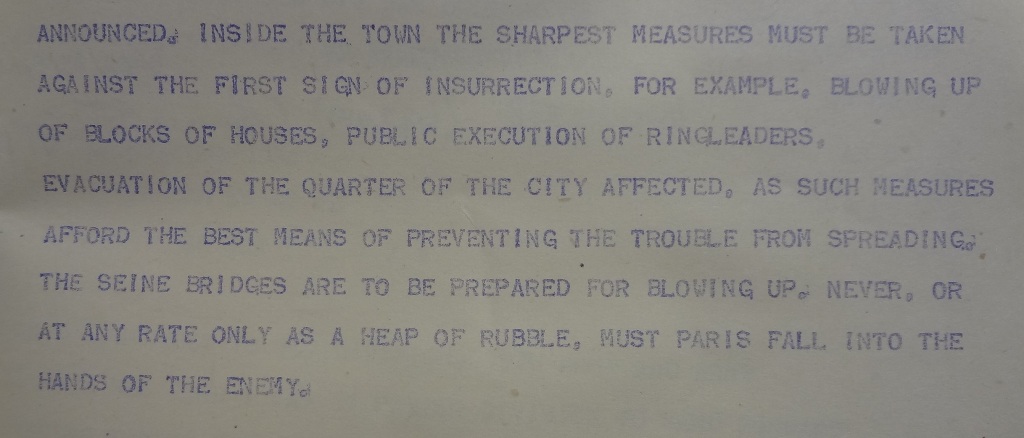

A few days after the liberation, a report signed by Eisenhower described Paris as ‘substantially undamaged’; Hitler’s plans for the French capital had been entirely different. While he apparently never asked whether Paris was burning, he still ordered: ‘never, or at any rate only as a heap of rubble, must Paris fall into the hands of the enemy’. The bridges, the monuments, the museums, everything was to be blown up. Fortunately, nothing was done to carry out the Führer’s order – not because von Choltitz had a cultural, sentimental attachment to Paris, as he later claimed, but because the Germans simply didn’t have the means to do so.

For the Parisians, it was the end of the war. Half-starved, they could finally see their own colours flying over the city, take the German sign-posts down, and take a triumphal break before embarking on what was to be a painful reconstruction process.

And for me, born in Paris four decades after the events I’ve just told you about, despite the terrible scenes of popular anger and mob justice which followed, the liberation of Paris still is a powerful symbol of national identity and national mobilisation. Cadran, the British Government’s magazine for liberated Europe, couldn’t have put it better: ‘by liberating themselves, the Parisians showed the world that the soul of a people is invincible, stronger than the most powerful war machine’.

So it isn’t without some form of national pride that I shall conclude by saying, exactly like the General 70 years ago, ‘Vive la France’!

[…] ‘Paris fights today so that France can speak tomorrow’ […]

Dear Dr. Desplat,

I wonder whether perhaps you would know the exact date that Hitler sent this telex ordering von Choltitz to destroy Paris (as seen in the above extract)?

Best,

M