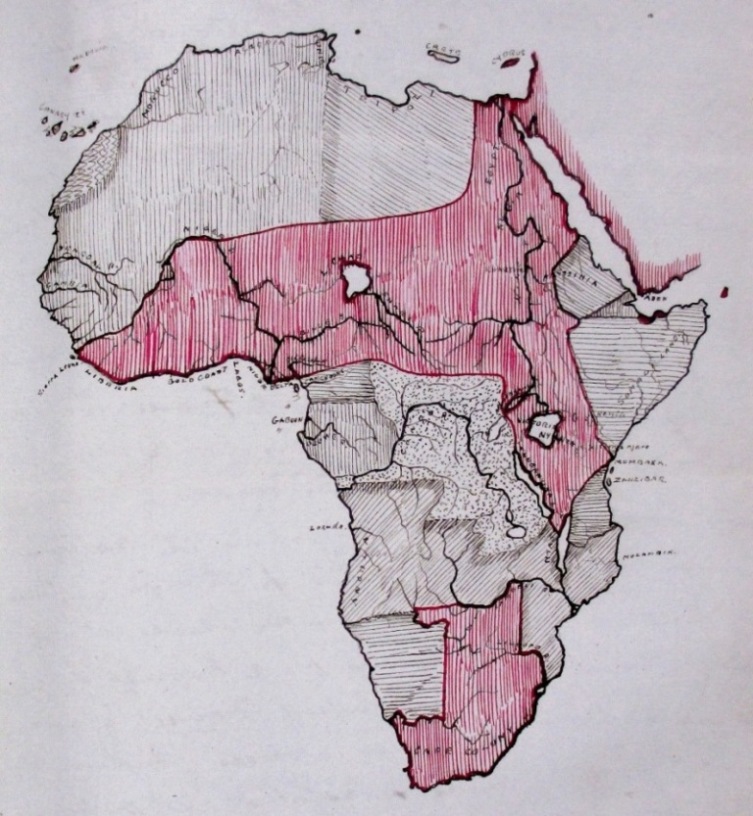

Mr Johnston's 'fantasy' map of Africa, showing his proposed British territorial claims in red (reference: FO 84/1750 f 54)

Some of The National Archives’ most interesting maps are not kept as separate flat, rolled or folded sheets, or even as part of atlases. Instead, they are to be found within boxes, files or volumes of official correspondence and other mainly textual records. Most such maps are not yet described individually in our online catalogue. Today’s blog post is about one of them.

This sketch map of Africa is drawn onto a page within a volume of Foreign Office correspondence (reference: FO 84/1750 f 54). It forms part of a letter sent on 13 November 1886 from Mr H H Johnston, Vice Consul for Territories Adjacent to the Oil Rivers, 1 Old Calabar, to Sir Percy Anderson, Senior Clerk at the Foreign Office.

Detail from a German map, showing Old Calabar and the surrounding area in 1886 (reference: FO 925/872 sheet 5). British territory is marked in orange and German territory in pink

Johnston’s map does not attempt to show Africa as it actually was in 1886. Instead, it shows his ideas about how the continent could be divided between European colonial powers to the UK’s advantage. Although many coastal areas and some parts of the interior had been colonised long before 1886, much of the interior of Africa did not yet have fixed boundaries that were recognised by European countries.

The mapmaker

Johnston’s letter gives the impression that he was frustrated in his job – he complains of poor health and an obstructive senior colleague – and he seems uninterested in Africa except as a resource for improving the economic and political power of his homeland. When I read the article about him in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 3 I realised that this impression was very misleading.

Johnston’s full name was Henry Hamilton Johnston, though he was usually known as Harry. 4 At the time he drew this map, he was 28 years old and, as an experienced traveller and author, was already considered to be an ‘authority’ on Africa. He went on to have a successful career as a senior administrator and diplomat in various parts of Africa, 5 as well as making important contributions to the study of African languages and natural history, and he was knighted in 1895.

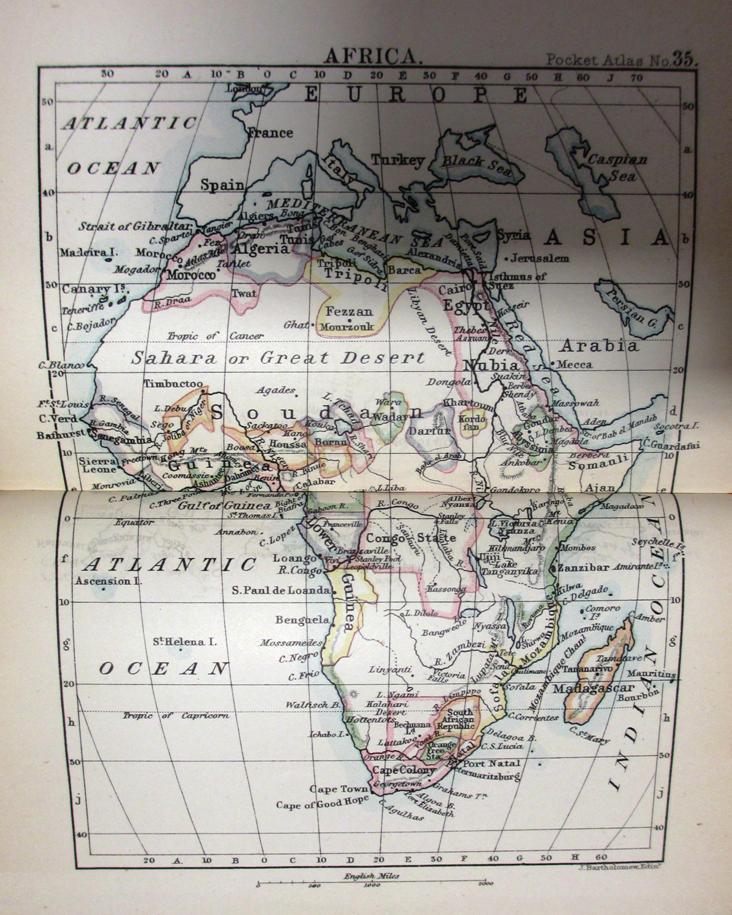

A more conventional map of Africa, from a Bartholomew pocket atlas published in 1886 (reference: FO 925/4163 plate 35). Much of the continent is shown as white space

Like many educated British people during the late 19th century, Johnston originally assumed that black Africans must be intellectually and culturally inferior to white Europeans. Later in life, as he came into contact with people of African descent on a more equal footing, he realised that he had been mistaken.

Mapping unreality

Supplying a map of an imaginary or fictional landscape can be a very effective way of making a narrative seem more convincing to a reader or viewer. Like Johnston, many writers have exploited this fact to make their stories or descriptions more ‘real’. Other people have made ‘fantasy’ maps as works of art or simply for fun.

Fantasy maps reflect reality and unreality to varying degrees. Some, like this map of part of J R R Tolkien’s Middle Earth, are pure imagination. Others, such as this map of Borsetshire and this map of Albert Square, show fictitious places set within the real world. Other maps depict real places in a fictitious way. For example, this map supplies the real city of Montevideo, Uruguay, with an imaginary metro system, and this map portrays Australia as Tolkien might have conceived of it.

Closest to Johnston’s map are those illustrating works of ‘counterfactual history’. Two examples are Robert Harris’s Fatherland, set in a world where Germany won the Second World War, and Sophia McDougall’s Romanitas, in which the Roman Empire has lasted to the present day. Such maps show real places not as they are, or ever were, but as they might have been.

Although in retrospect Johnston’s sketch can be seen as a fantasy map, it seems likely that he would have found this view puzzling, and perhaps even offensive. He drew his map as a serious suggestion and expected his colleagues in London to treat it as such.

There is no sign that Johnston or his contemporaries had any doubt of the UK’s right to assume control of land or argue for particular boundaries 6 based purely on its own interests. Whilst writers of fiction can let their imaginations run wild harmlessly, the late 19th century ‘authors’ of the scramble for Africa had a real and enduring effect on the landscape and people that they divided between them.

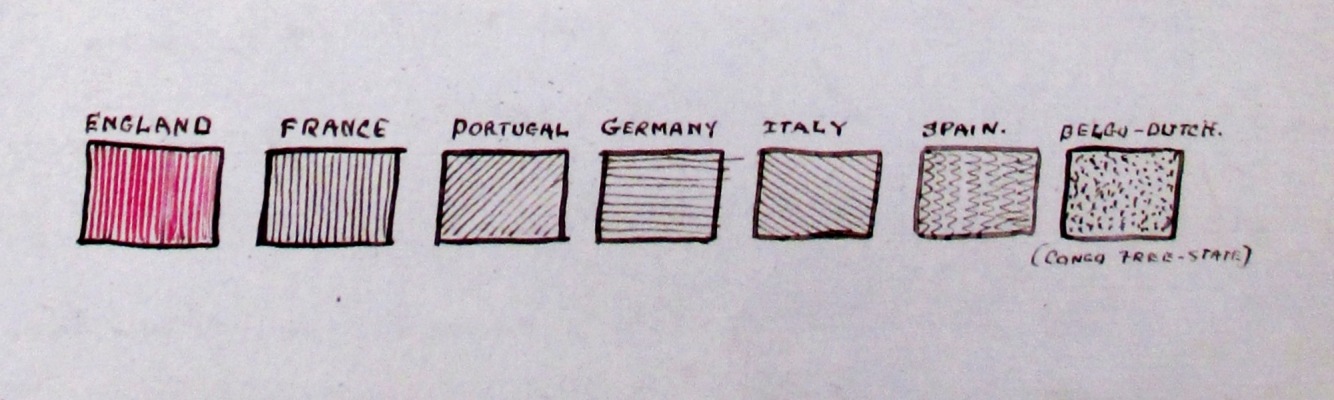

The key to Johnston's map (reference: FO 84/1750 f 54)

Notes:

- 1. These territories correspond roughly to the south-eastern coastal area of present-day Nigeria. ↩

- 2. For instance, compare Johnston’s sketch with this map published in 1897, particularly along the western ‘bulge’. ↩

- 3. This website is not free to access but many libraries in the UK subscribe to it. ↩

- 4. If, like me, you are curious to know what he looked like, there are some portraits on the National Portrait Gallery website. ↩

- 5. Ironically, he was instrumental in ensuring that the boundaries between British and Portuguese colonies in southern Africa were settled very differently from those he had proposed in 1886. ↩

- 6. One legacy of the British Empire and the UK’s historically prominent role in world affairs is that The National Archives holds many maps and other records useful for researching international boundaries. ↩

Henry Hamilton Johnston was my 1 st cousin 3xremoved and I ‘discovered’ him when I became interested in tracing my family tree. It is interesting to read this and see his maps. There is much more information about his own view in his autobiograthy ‘The Story of my Life’ and a later biograghpy by his brother, Alex Johnston, ‘The letters of Sir Harry Johnston’.

The colonial view that prompted the ‘scrabble for Africa’ is very outmoded now and most definately non-PC, but if you are interested in the political science of the late 19th century both books are worth a read.

Harry was a short man with a squeaky voice, he had a sense of humour and was a very gifted artist and linguist. Very much a man of his times. When he returned to England after his last spell in Colonial service he was somewhat dismissed. Still quite a young man, I think about 47, his face did not fit and the nation lost what might have been a clever political brain.

Thank you for your comment, Marion. It’s interesting to hear a different perspective on the same person.

A former colleague of mine was fond of saying that all history is someone’s family history and your story is a perfect example of that.