The movie industry has a long history of flops. This is the story of a film made nearly 100 years ago that culminated in litigation and a court case.

In 1919, just over a couple of decades after the first British feature film was produced, the silent movie ‘The Lackey and the Lady’ was completed in England. It tells the story of the daughter of a wealthy banker married to a servant who ran off with him to Australia, and was based on a novel by Tom Gallon.

Copyright photographs of the author of the book The Lackey and the Lady, Tom Gallon (catalogue reference: COPY 1 492 147 (2))

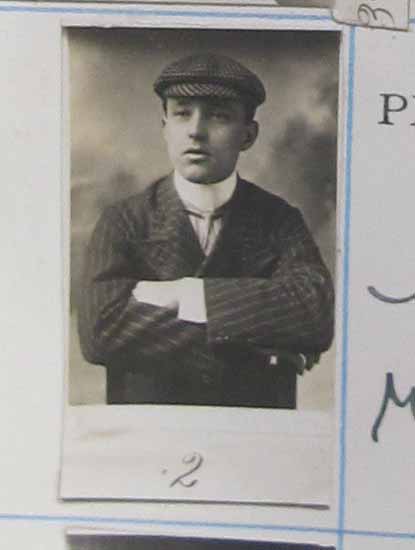

Copyright photograph of actor in The Lackey and the Lady, A E Matthews (catalogue reference: COPY 1 470 233)

Probably the only familiar name attached to the film is actor Leslie Howard, of Gone with the Wind (1939) and Scarlet Pimpernel (1934) fame. Other performers were A.E. Matthews, Roy Travers and the French-born actress Mary Odette.

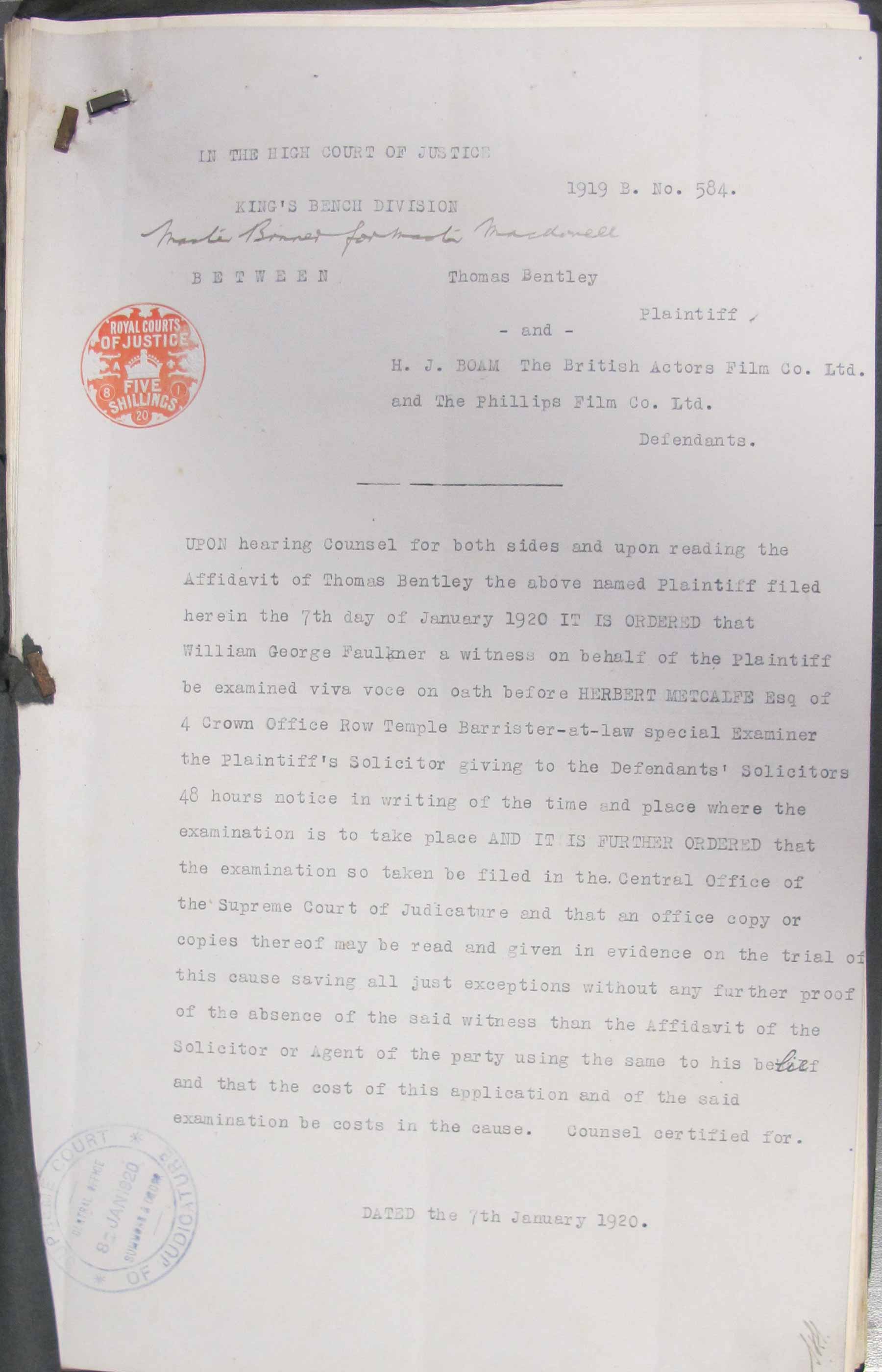

But the film and the performances of the actors were destined not to be judged by the world of cinema but instead in the judicial environment of court ushers and barristers’ wigs and gowns. In February 1920 the director, Thomas Bentley, brought an action for slander against Phillips Film Company, its distributor H J Boam and The British Actors Film Company, in the King’s Bench Division of the High Court.

The film was meant to be shown at a trade show at Shaftesbury Pavilion in London. Just before showtime, Boam – who had been in dispute with Thomas Bentley – came on stage to declare that ‘The Lackey and the Lady’ would not be shown, as it was ‘not up to standard to be placed before you’. The film had previously been shown to Boam and representatives of The British Actors Film Company and had been passed as satisfactory.

The National Archives hold the court records for the case. The pleadings are under the reference J 54/1718, and the transcript of the pre-trial examinations of witnesses undertaken by lawyers are under reference J 17/601. This produces some illuminating and entertaining exchanges about the quality of the film.

An expert witness William George Faulkner, the film reviewer for the Evening News, was questioned by one of the barristers for the plaintiff Thomas Bentley, before the court appointed barrister called a Special Examiner.

An example below concerns a scene in the film where the horse belonging to the lady runs away.

Question: This was a ludicrous portrayal of a runaway horse, was it not?

Answer: No, I do not think so.

Q: It did not show the slightest signs of running away at any time, did it?

A: Its speed was fast.

Q: Oh!

A: Relatively.

Q: Faster than a four wheeler, but not much?

A: Oh yes.

Q: Not very much.

A: That was the impression I had.

Q: Then it stopped to eat grass?

A: Yes.

Q: Then the other horse joined it, a very calm looking couple of horses?

A: I do not think they looked very blown.

Q: Do you think a very critical audience would have thought this rot?

A: No, candidly I do not think they would.

Q: What do you think they would have thought of it?

A: I think they would have been more interested in the human side of the scene than the horses.

Q: Do you not think they would have been more interested at the efforts of that horse in its dramatic runaway?

A: No, I think the whole of their attention would have been concentrated on the two persons concerned.

Q: Why do you think the lackey kissed the young lady?

A: Why?

Q: What do you think he was after?

The Special Examiner: It is rather an embarrassing question.

A: I will tell you what my impression is. My impression was from the manner he took her from her horse when she fainted and kissed her that he was in love with her.

At the end of the trial the judge Lord Chief Justice Rufus Isaacs 1st Marquess of Reading, the first Jewish Lord Chief Justice, gave his summing up. He stated that the film industry seemed to have created a language of their own which was apparently in conformity with the method of taking the pictures. The jury then answered the following questions – Are the statements true? No. Were they made with malice? No. What damages? £350 awarded to the plaintiff Thomas Bentley.

The publicity emanating from the film and subsequent trial, not surprisingly damaged the reputation of the British Actors Film Company. Its film production arm was taken over by a larger company a few years later and it was finally dissolved in 1929. The National Archives hold the Board of Trade dissolved companies file for the British Actors Film Company under reference BT 31/22989/141610.

Thomas Bentley case, King’s Bench Division – examination of witnesses (catalogue reference: J 17/601)

A print of the film unfortunately does not exist at the British Film Institute. However, stills from the film do exist, as they appear in the 30 January 1919 edition of the Kinematograph Weekly and an internet search provides images of these stills.