On 30 October 1918 an armistice was signed with the Ottoman (Turkish) Empire, bringing an end to the Turkish Army’s participation in the war.

Turkish troops surrendering to British forces. Catalogue reference ZPER 34/153 July – Dec 1918

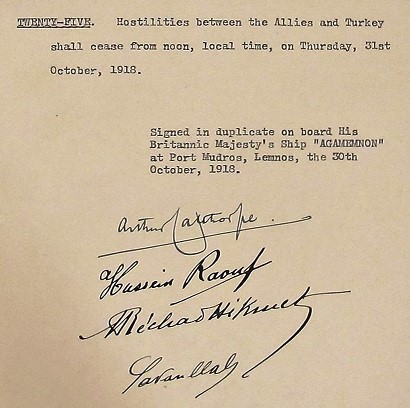

The armistice was signed on board HMS Agamemnon at Port Mudros, on the island of Lemnos, on 30 October 1918. Vice-Admiral Arthur Calthorpe, Commander-in-Chief of the British sector in the Mediterranean, signed on behalf of the Allies; Hussein Raouf, Turkish Minister of Marine, Rechad Hikmet, Turkish Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs, and Lieutenant Colonel Saadullah, signed under the authority of the Turkish Government.

Signatories of the Armistice of Mudros. Catalogue reference FO 93/110/80

The entry of the Ottoman Empire into the war on the side of the Central Powers in November 1914 had greatly extended the geographical scope of the conflict. As well as Anatolia – the area containing what is now Turkey – theatres of war sprang up in North Africa, across the Levant and the Middle East, and in Transcaucasia. This, crucially, cut off trade into the Black Sea: a vital artery for Russia.

Ottoman Empire: Map of turkey in Asia, 1794. Catalogue reference SP 112/91

Attempts to knock Turkey out of the war early in 1915 failed. This would have involved taking the Dardanelles straits and the Gallipoli peninsula, providing a quick route to the Turkish capital of Constantinople.

On the Russian front, in April 1915 the Armenian population of the eastern city of Van rose up against the Ottomans in response to growing violence from the Turkish majority. The Armenians seized the city but were soon besieged. Bitter fighting continued in the area for much of 1915. This led to the forced deportation of virtually the entire Armenian community in eastern Anatolia. The deportation was accompanied by widespread robbery and murder, and culminated in forced marches across the Syrian desert. This policy resulted in death on an extraordinary scale (FO 371/2488).

The campaigns in North Africa, the Arabian peninsula and the Persian Gulf were largely concluded by the end of 1917. (If you wish to find out more about those particular campaigns, please visit our web pages on the First World War in the Middle East.) However, the campaigns in Palestine and Mesopotamia (now Iraq) dragged on until the end of the war.

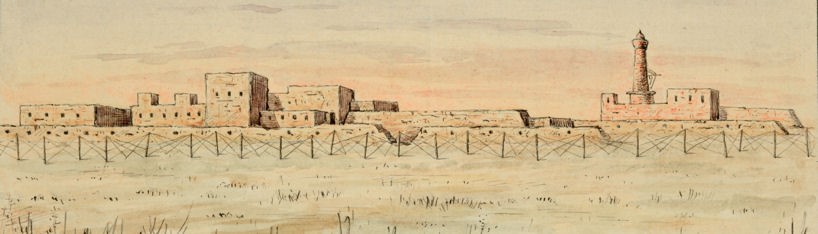

In Mesopotamia, following early success, the British and Commonwealth advance was halted in November 1915 at Ctesiphon on the river Tigris, 35 miles south-east of Baghdad. The British commander, General Charles Townshend, retreated to Kut al-Amarah, closely followed by Turkish forces. The Kut garrison, comprising some 2,765 British and 6,000 Indian soldiers, surrendered on 29 April 1916. The survivors – including General Townshend – were marched off to Turkey as prisoners of war (WO 32/5215).

Watercolour of the Liquorice Factory at Kut by Muhammed Amin Bey. Catalogue reference CAB 44/35

On 25 February 1917, Kut was retaken by British forces. The Turks were pursued to Baghdad, which was captured on 11 March 1917. In December 1917, with British forces now overwhelmingly in control, a small force under General Lionel Dunsterville separated from the main forces and crossed Persia to assist in the recapture of Baku on the Caspian Sea – although the objective was not retaken until August 1918. On 25 October 1918 the city of Kirkuk in the north of Mesopotamia was occupied, marking an end to much of the Turkish opposition (WO 106/915-917).

In Palestine, following heavy losses at Gaza, General Edmund Allenby replaced Sir Archibald Murray in command of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force. On 1 November 1917, the Turkish army was forced into a general retreat and British forces closed in on Jerusalem. The holy city of Jerusalem was taken on 8 December 1917. However, final operations in Palestine began on 19 September 1918, due in part to the redeployment of troops to the Western Front. In October 1918, Allenby reported to the War Office that the operation had ‘resulted in the destruction of the enemy’s army, the liberation there of Palestine and Syria, and the occupation of Damascus and Aleppo.’ (WO 32/5128)

Left to right: Vice-Admiral Sir Arthur Calthorpe, signer of the armistice on behalf of the Allies; General Sir Charles Townshend, liberated to inform Admiral Calthorpe that the Turks requested an armistice; General Sir Edmund Allenby, Commander of the British Expeditionary Force in Palestine and Syria. Catalogue reference ZPER 34/153

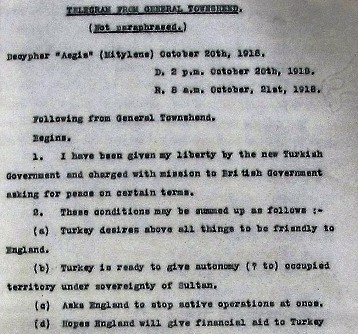

The surrender of Bulgaria in September 1918 severed the supply lines from Germany to the Ottoman Empire and placed Allied troops within striking distance of Constantinople. With Turkish forces in retreat on all fronts, there was no chance of meeting this new threat: leaders in Constantinople realised that they needed to sue for peace. On 20 October 1918, General Charles Townshend was freed from being a Prisoner of war in Constantinople and tasked by the Turks with communicating their request for peace.

Telegram from General Townshend, 20 October 1918. Catalogue reference ADM 116/1652

Throughout October, Allied heads of government met their opposite numbers to discuss strategy on handling peace negotiations and the terms of armistices and terms of peace to be applied to the remaining Central Powers: Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire.

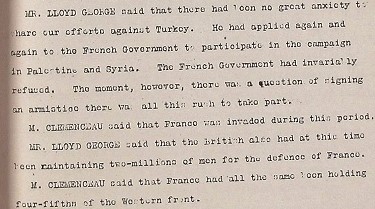

At a three power meeting between Britain, France and Italy, held at the Palace of Versailles on 30 October 1918, things really came to a head. David Lloyd George revealed to his counterparts – Clemenceau and Orlando – that a telegram was on its way from Mudros. It announced that Admiral Calthorpe would have the terms of an armistice with Turkey signed that evening. In an extraordinary series of petulant outbursts, the French and Italian premiers and their foreign secretaries (Stephane Pichon and Baron Sonnino) made very clear their displeasure at having been left out of the loop.

Three Power discussion at the Palais de Versailles, 30 October 1918. Catalogue reference ADM 116/1652

Here is an edited version of that meeting:

M. PICHON said that the armistice proceedings had failed to partake of an allied character.

MR. LLOYD GEORGE said that the British had always been in command of the North Aegean. When it had been a question, in the naval attack on the Dardanelles, of leading 9 or 10 battleships, the French had been very willing to leave the command in British hands.

M. CLEMENCEAU said that in these matters, the question of national susceptibility arose which could not be put aside.

MR. LLOYD GEORGE said that when questions of national dignity and susceptibility were raised, France was the last nation that ought to complain.

MR. LLOYD GEORGE pointed out that except for Great Britain no one had contributed anything more than a handful of black troops to the expedition in Palestine. He was really surprised at the lack of generosity on the part of the French Government. The British had now some 500,000 men on Turkish soil. The British had captured 3 or 4 Turkish Armies and had incurred hundreds of thousands of casualties in the War with Turkey. The other Governments had only put in a few black [original term changed] policemen to see that we did not steal the Holy Sepulchre.

When, however, it came to signing an armistice all this fuss was made. There had been no great desire to share our efforts against Turkey. He had applied again and again to the French Government to participate in the campaign in Palestine and Syria. The French Government had invariably refused. The moment, however, there was a question of signing an armistice there was all this rush to take part.

M. CLEMENCEAU said that France was invaded during this period.

MR. LLOYD GEORGE said that The British also had at this time been maintaining two-millions of men for the defence of France.

M. CLEMENCEAU said that France had all the same been holding four-fifths of the Western front.

MR. LLOYD GEORGE regretted that when the Conference were making so much progress with other matters this minor question had been raised.

M. CLEMENCEAU said that he had not raised it.

M. PICHON said that the French Government had always recognised that the armistice must be signed by the Commander-in-Chief. If Marshal Foch signed it, this would be as General-in-Chief on the Western front. If General Diaz signed it, it would be in his capacity as Commander-in-Chief of the Italian front. Admiral Calthorpe, however, was not the Commander-in-Chief in the Mediterranean.

MR. BALFOUR pointed out that the Dardanelles, Bosphorous, and Sea of Marmara were not in the Mediterranean. It was true that Lemnos, where the armistice was to be signed, was in the Mediterranean. The locality with which the armistice dealt, however, was not in the Mediterranean.

M. PICHON said that, after a few minutes conversation with M. Clemenceau and Baron Sonnino, that they would accept the fait accompli.

The armistice lasted until a peace settlement was concluded. The Treaty of Sèvres was signed on 10 August 1920, following the Paris Peace Conference. As part of the conditions of peace, the frontiers of the Ottoman Empire were redrawn to the borders of Anatolia, which equates to modern Turkey. This was to be further divided up, with the creation of autonomous Armenian and Kurdish states and French, Italian and Greek spheres of influence (FO 93/110/81).

Turkish troops on their way to internment. Catalogue reference ZPER 34/153

The Ottoman signing of the Treaty of Sèvres delegitimised the regime in the eyes of many Turks and gave considerable momentum to the Turkish nationalist movement. The Ottoman institutions were swept away and a modern Turkish state was formed under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the hero of Gallipoli.

The subsequent Turkish War of Independence saw Turkish forces defeat the Greeks in the west, as well as the nascent Armenian state in the east, to establish de facto control over Anatolia. This was eventually recognised by the international community; the boundaries of modern Turkey were established at the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923 (FO 839/48).

We plan to publish more blog posts in the series Milestones to Peace over the next few months, to coincide with the armistices signed by Austria-Hungary and Germany.

We are also hosting a variety of activities to mark the anniversary of the Armistice with Germany and the end of our centenary programme, First World War 100.

All of the armistices and treaties will be shown together for the first time during the conference ‘Peace making after the First World War’ , which takes place from Thursday 27 to Friday 28 June 2019.