Today sees the publication of our new book, Maps: their untold stories.

In this book we explore 100 maps selected from the vast, extraordinary and diverse collections here at The National Archives. Our journey spans seven centuries, and we visit places all around the world, from New York to New Zealand. There are even locations not found in the world gazetteer, such as Purgatory and Treasure Island.

We have always emphasised that the maps held here are an integral part of the wider historical record. When writing our book, we often looked at other records in the archives to help us to understand the origin and significance of the maps. We have included images of some of these related items in the book, from medieval seals to modern photographs.

Scholars who have written about the theory and practice of archives have found various ways of characterising the records and their importance. For instance:

- archives as historical evidence and as authentic records of past activity and decision-making

- archives as sources of power or, alternatively, as sources of accountability

- archives as memory or as a record of events in history as seen through contemporary eyes

- archives as beautiful or stimulating objects

- archives as stories

In our book we show how maps fulfil all these roles, but especially the latter two. We present the maps as fascinating and treasured objects, and we tell some of the stories that lie behind them. Who made them? Why were they made? What do they reveal about the society, politics, events or ideas of their eras?

In this blog post we also explore the ideas behind the book’s title, by looking at ways in which maps themselves tell stories. Here are just a few examples.

Maps tell stories in that they can represent the viewpoint of their makers or commissioners. They may tell a specific story, from one side, when in fact there may be other viewpoints, especially in legal cases.

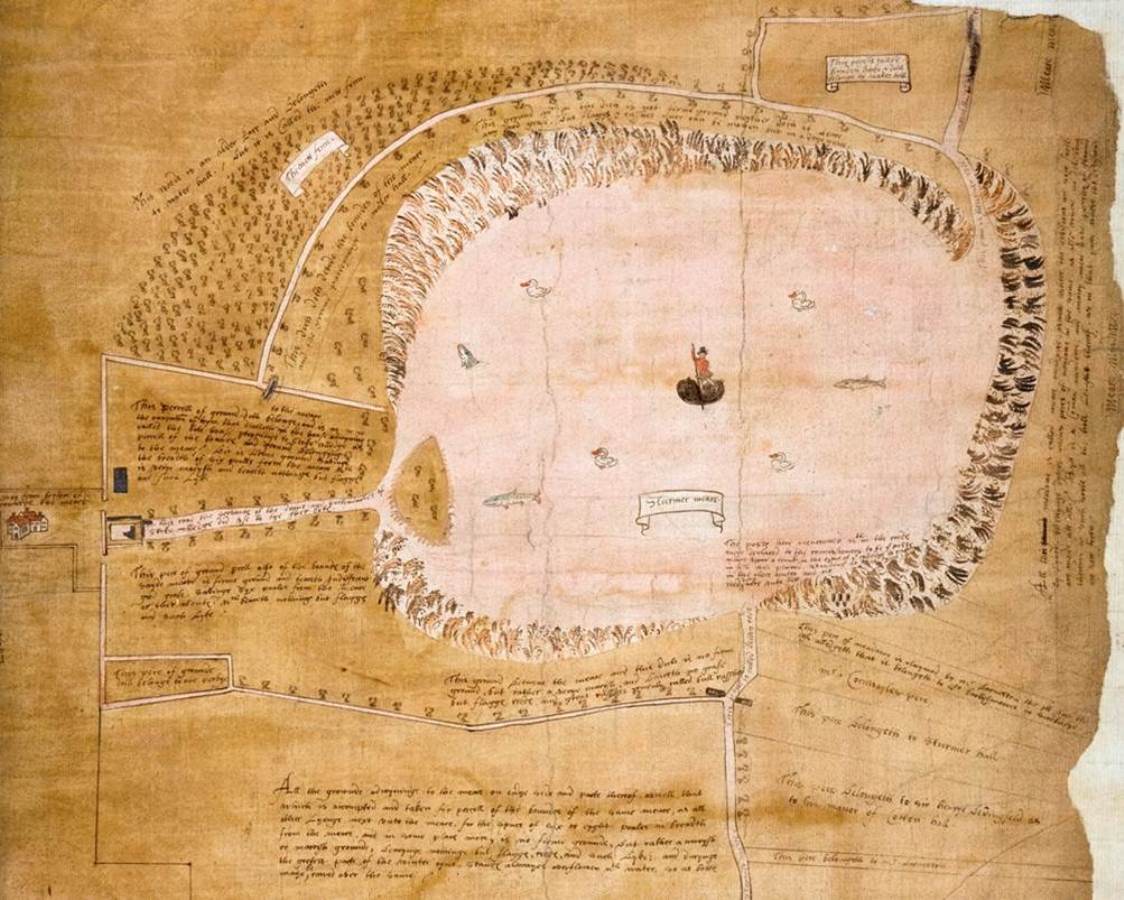

Two maps were made for a dispute about fishing rights on Sturmer Mere in Essex in the summer of 1571. We only have this map, which shows a wetland landscape; reedy fringes, fish and swans surround a boatman in Elizabethan garb (MPC 1/33).

Ownership of a boat, which would be needed to fish this lake, was part of evidence for one party in the case – that of the mapmaker. The other party’s map, if it had survived, might show a different view. We may need to be careful about expecting maps to represent reality.

Just like other historical sources, maps don’t always tell the truth. On many old maps, California is shown incorrectly as an island. This example comes from a map by the Dutch cartographer Carel Allard, published in about 1700 (ZMAP 2/1, vol 2, plate 113)

The strange geographical myth of the island of California became popular in the early 1600s and, despite reliable reports to the contrary, it persisted on some printed maps for more than a century.

Many European mapmakers – and their paying customers – preferred the ‘traditional’ portrayal over something more modern and accurate. Why let the facts get in the way of a good story, or of a good map?

The location Porto de Francisco Draco shown on this example is named after the English explorer Sir Francis Drake, who visited this region in 1579. Drake called the area New Albion (written here in Latin as ‘Nova Albion’) after an ancient name for Great Britain.

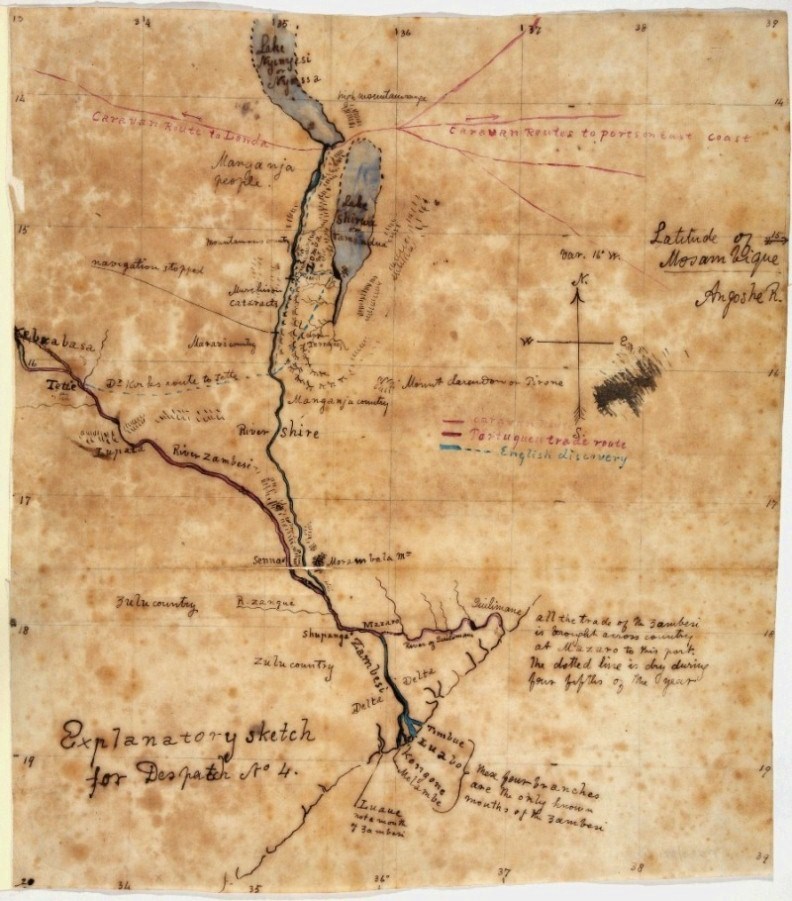

Looking at maps alongside related archival material may tell a wider story than looking at maps alone. The relationship is spelt out in the caption on this map ‘Explanatory sketch for Despatch No 4’ (MPK 1/422, item 1). A hand-drawn map on tracing cloth, blotched by moisture and ink runs, it evokes the heat of the African interior.

The note was written by David Livingstone, at a point when, as happened to so many explorers, he found unexpected obstacles in his way. He was halted by cataracts on his progress up the River Shire to what is now Lake Nyasa.

Using his enforced stop to relate his progress to the Foreign Secretary, Livingstone sent the map in a letter dated October 1859, in which he famously stated: ‘no white man had traversed the country before’.

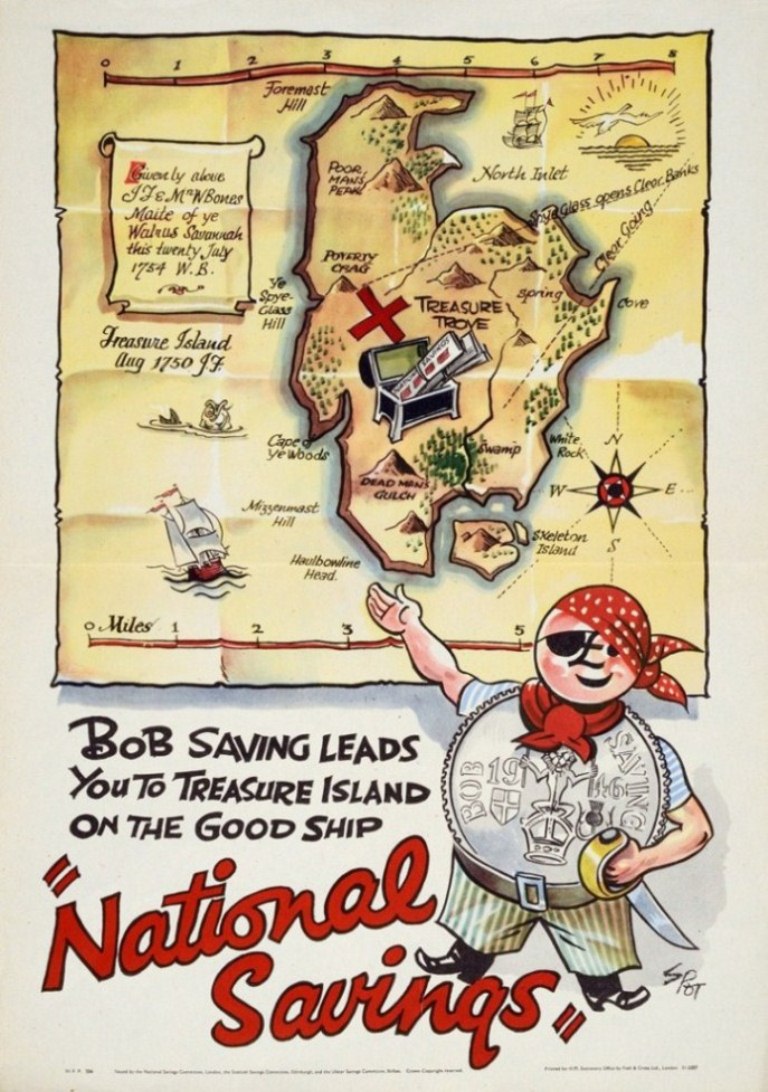

The classic children’s book Treasure Island, by Robert Louis Stevenson, was written because of a map. The story was partly inspired by a plan of an imaginary island drawn by the author’s stepson, Lloyd Osbourne.

Many editions of the novel include a map of the island. It’s this map that inspired the poster design shown above, which is effectively an affectionate parody of a fictional treasure map (NSC 5/215).

The poster was used to advertise National Savings in the late 1940s. It is a fine example of how maps can be used to attract attention and to make a point in an immediate and compelling way. Note that the treasure chest is filled with savings certificates instead of the more traditional gold and jewels. Look carefully at the shape of Captain Bob Saving’s nose: it’s a pound sign!

As archivists, we can, of course, only agree with the broader message that you should take good care of your valued treasures. The fact that so many wonderful maps are now preserved here at The National Archives ensures that they – and their stories – have a place in history.

Maps: their untold stories is available to buy from The National Archives’ bookshop.

On 25 September we will be presenting a free talk about the book and some of the maps featured in it. We would be delighted to see you there.

[…] Maps: telling their untold stories […]

Hello Rose

On page 22 and 23 there are maps of Haldenby and surrounding area. Would it be possible to email a high resolution copy of the map on p23? It is my area and am researching the history. Do you have any other older (pre 1800s) maps of the Isle of Axholme/River Trent-Ouse-Don mouth, SE of the River Humber?

Regards

Andrew

Love that island of California! Just like northwest passage and more, to us it all seems so simple and easy to forget how many centuries of exploration before we would ever have the familar maps we take for granted today

Interesting thought that 2 maps of the same place could tell a different story.

Look forward to reading the book

[…] Maps tell stories in that they can represent the viewpoint of their makers or commissioners. They may tell a specific story, from one side, when in fact there may be other viewpoints.— Andrew Janes & Rose Mitchell, Maps: Telling Their Untold Stories […]

Book has arrived. Love it – fascinating background to the maps.

[…] also got a book called Maps: their untold stories which includes 100 maps from the collection at the National Archives. It’s a […]

[…] Maps tell stories in that they can represent the viewpoint of their makers or commissioners. They may tell a specific story, from one side, when in fact there may be other viewpoints. — Andrew Janes & Rose Mitchell, Maps: Telling Their Untold Stories […]