Browsing a bookshelf in search of inspiration

A few years ago, a colleague asked me for help in finding a map. What he wanted, he told me, was a fairly up-to-date map that showed Great Britain at ‘a normal scale’.

After laughing briefly at him, and then apologising for my rudeness, I plucked a road atlas from one of the bookshelves in our staff reading room. Fortunately, this seemed to fit the bill perfectly.

With the benefit of hindsight, I think that there are two morals to this story:

1. What is obvious to one person is not obvious to another. Like any good researcher, my colleague should have tried to explain what he wanted in a less ambiguous way. Equally, like any good public services archivist, I should have helped him to shape his request into something more sensible.

2. There is no such thing as a ‘normal’ map. The features and attributes of any map (including its scale) depend on its purpose. Why was it made and what was it intended to be used for? Two maps of the same place made at roughly the same time, but for different reasons, can look quite unlike one another.

Suppose, for instance, that you wanted to look for a map showing part of Nottingham during the early twentieth century. [ref] 1. I chose Nottingham because I recently spent a weekend there visiting friends. I could have chosen many other places with much the same result. [/ref] Here are three examples of our maps that fit these criteria.

The dashed line on this map represents the route taken by the Zeppelin. Catalogue reference: MPI 1/604/6

This hand-drawn map [ref] 2. MPI 1/604/6. [/ref] comes from Air Ministry records. It was made to show the impact of a Zeppelin air raid that took place very early in the morning on 24 September 1916. The little crosses in circles mark where bombs fell.

It is a very interesting map in its own right – especially when read alongside other papers about the incident [ref] 3. AIR 1/584/16/15/183part2, ff 451-455 are reports and eyewitness statements. [/ref] – but its detail is quite limited. It does not record very much information about the geography of Nottingham at that time.

The red lines marking agreed and proposed tram routes were probably added to this street plan in about 1902. Catalogue reference: RAIL 1033/91

My second example [ref] 4. RAIL 1033/91. [/ref] is a commercially-published street map dating from around 1900. Although the publisher intended it to be a general-purpose map for locating places within the city – and it can still serve that function for researchers today – it was also given a more specific use.

The map comes from railway company records. The red lines were added by hand to show routes for the new electric trams, which were then becoming an important mode of public transport in British towns and cities.

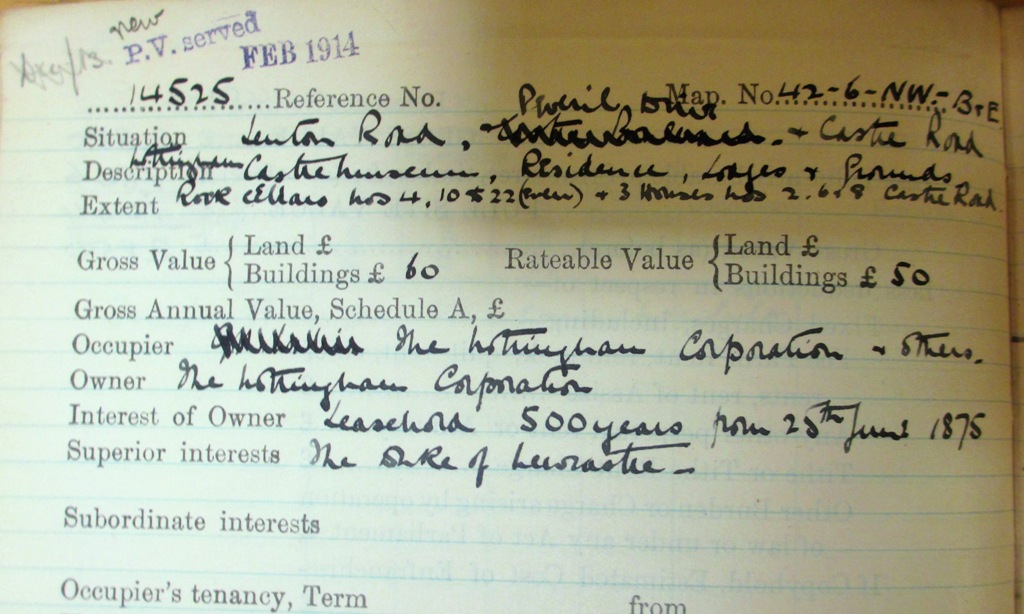

Detail from Ordnance Survey sheet Nottinghamshire XLII 6 NW. This is one of about 40 Valuation Office maps covering Nottingham. Catalogue reference: IR 130/9/273

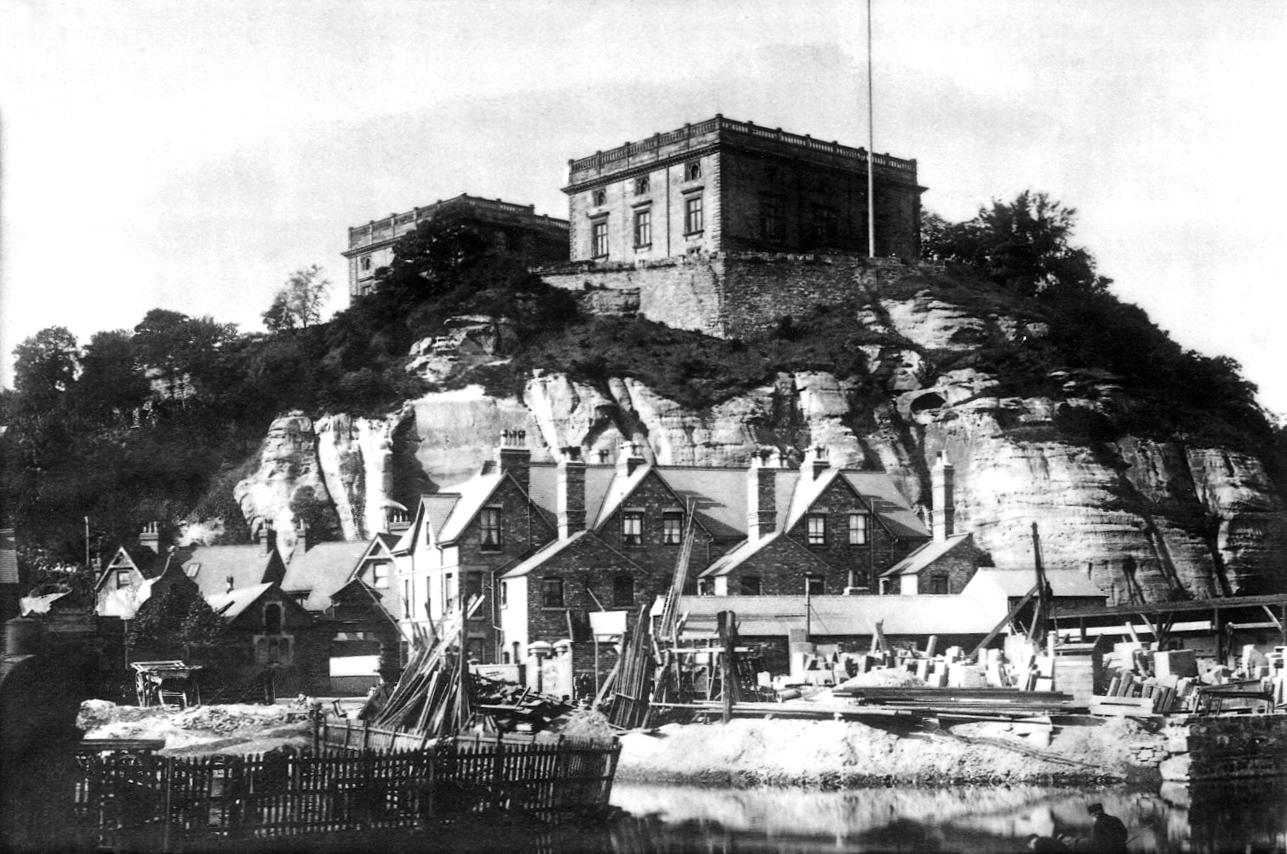

Finally, this heavily annotated Ordnance Survey map [ref] 5. IR 130/9/273. [/ref] was produced as part of the Valuation Office survey carried out between 1910 and 1915. This particular example is an enlargement at the scale of 1:1,250 and was printed specially in 1911. [ref] 6. This map bears the scars of old damage. Long before it came to the archives, a well-meaning official in a District Valuation Office tried to repair it with ordinary sticky tape, which ultimately did more harm than good. [/ref]

The maps and related field books from this survey provide a useful snapshot of land and property in England and Wales on the eve of the First World War. [ref] 7. For instance, one of the properties shown on this map is Nottingham Castle. The relevant field book entry (IR 58/63072, no 14525) includes a detailed description of the building and grounds. [/ref] They are very popular with researchers, including family and local historians.

None of these three maps is intrinsically ‘better’ or ‘worse’ than any of the others. Each was made and kept for different reasons, and each offers different information to researchers today.

If you want to look for an old map and you think that The National Archives might have what you want, the map pages on our website are your best starting point.

When searching, bear in mind that a map showing the right place at the right date may not suit your needs in other ways. In other words, think about ‘what’ and ‘why’, as well as ‘where’ and ‘when’.

Good article, I love maps, they reveal so much about an area at a certain time, just takes a little imagination, Especially useful when supported by written accounts or pictures to flesh out the landscape. I often find that its worth having a look at a map that will most likely have been created for a very specific reason that has nothing to do with your research. There will not be anything created that answers all your questions but a little digging will reveeal a lot. Like all archives I suppose.

Thank you for your comment, Sam. I’m glad you enjoyed the post.

I like this point very much: ‘There will not be anyting created that answers all your questions but a little digging will reveal a lot.’ I can see myself quoting this at the enquiry desk.