Could you live on £1 a week? Especially when you were told you could only buy certain things? This was just one of the rules which operated at Alexandra Palace from 1915 until 1919 – the time when the palace was turned into a civilian internment camp for German, Austrian and Hungarian enemies (FO 383/33). 1

Not being a local Londoner, it was only by chance that I stumbled across Alexandra Palace. Being German, I was fascinated by its varied and troubled history, particularly with regards to the First World War, and I wanted to find out more. This is exactly what I have been able to do over the past three months in my internship at The National Archives – part of my Public History MA course at St Mary’s University, Twickenham. The vast number of documents available at the archives reveal the almost forgotten history of Alexandra Palace.

‘The Palace for the People’

For those of you, who, like me, aren’t familiar with ‘Ally Pally’ (as it was nicknamed in the 1930s), here’s a brief history. Alexandra Palace – named in honour of the Danish Princess Alexandra who, in 1863, married the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) – is located in the North of London between Muswell Hill and Wood Green. The palace was originally built as ‘The Palace for the People’ (sounds grand, doesn’t it?) to cater for the education, entertainment and leisure of the masses. Things didn’t go smoothly, though. The planning process started in 1858 and the building process began in 1864, but financial difficulties continually overshadowed the project. The palace finally opened to the public on 24 May 1873, but disaster soon struck. Alexandra Palace burnt down on 9 June 1873, only 16 days after it had opened, and three palace workers died.

No time was lost. The palace was rebuilt in a mammoth project and opened again on 1 May 1875. A vast variety of attractions and events like concerts, plays, a cinema, a skating rink, a race course, water-chute rowing on a lake and a 3000-seat theatre were planned to attract the public (FO 383/469). However, this wasn’t sufficient to draw in a big enough crowd; low levels of public attendance – as well as expensive maintenance and heating charges – turned the project into a financial disaster. 2 The following years were marked by turbulent times and upheavals; the palace had to be closed and reopened again several times.

One man’s joy, another man’s sorrow

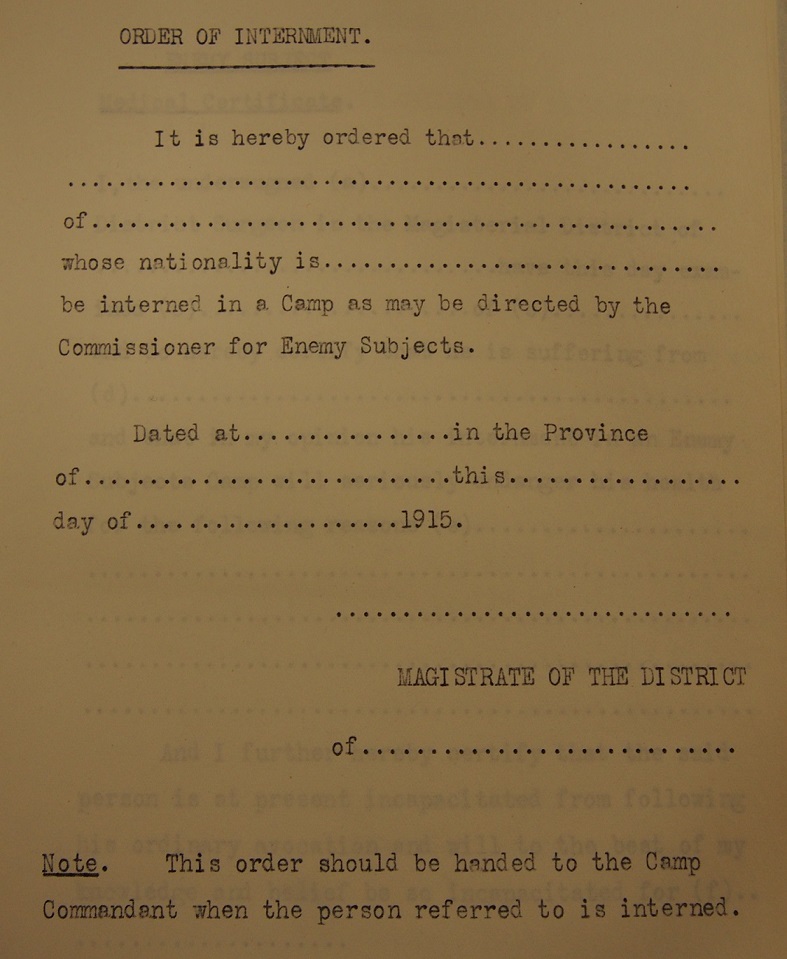

‘Order of Internment’ document, 1915 (catalogue reference: FO 383/33)

When the First World War broke out in 1914, Alexandra Palace was turned into a refugee camp for Belgians who were fleeing their country in the face of the German invasion (FO 383/469). The Aliens Restriction Act, passed in the same year, also meant Germans, Austrians and Hungarians were now ‘enemy aliens’: enemies to the country many of them considered home. They had lived, worked and married British women in the UK, but with the outbreak of the First World War, things changed. Following the act, they had to register with the police in the district where they lived. 3

It was not long before the British Government decided that all German, Austrian and Hungarian males between the ages of 17 and 55 were to be interned (FO 383/33). Ironically, Alexandra Palace turned from a place of shelter and security – a haven for Belgians who had escaped from German attacks in 1914 – to a place of captivity for people of German origin.

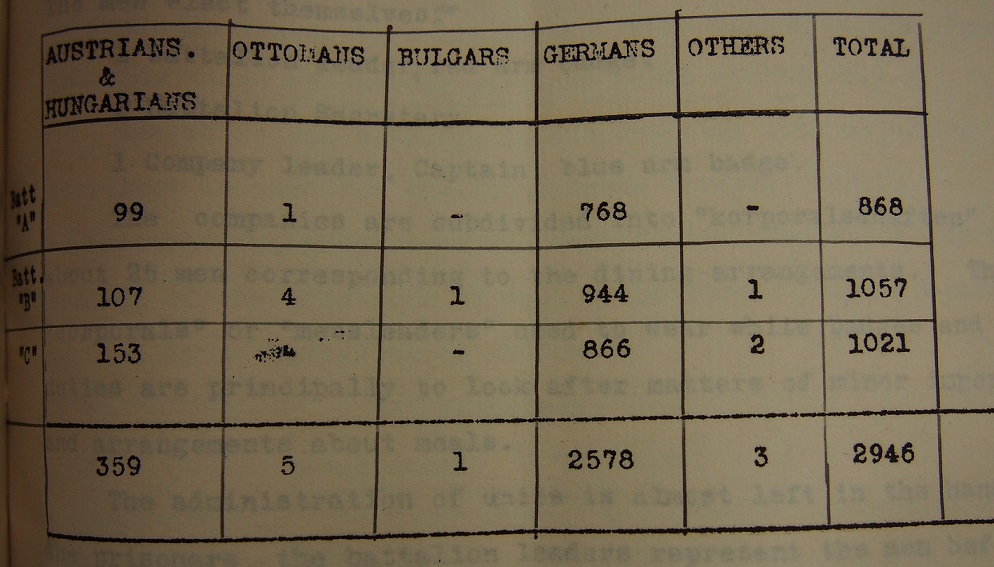

Number of prisoners and nationalities interned at Alexandra Palace, late 1917 (catalogue reference: FO 383/469)

From 7 May 1915 and for the next four years, 3,000 people would enter Alexandra Palace as prisoners.

Cigarettes, horse meat, ink and socks

Was it all bad? Officials at the time certainly didn’t think so. All internment camps across the UK were inspected on a regular basis, and thanks to The National Archives’ extensive materials and records, a report from 27 May 1915 still survives (FO 383/33). 4

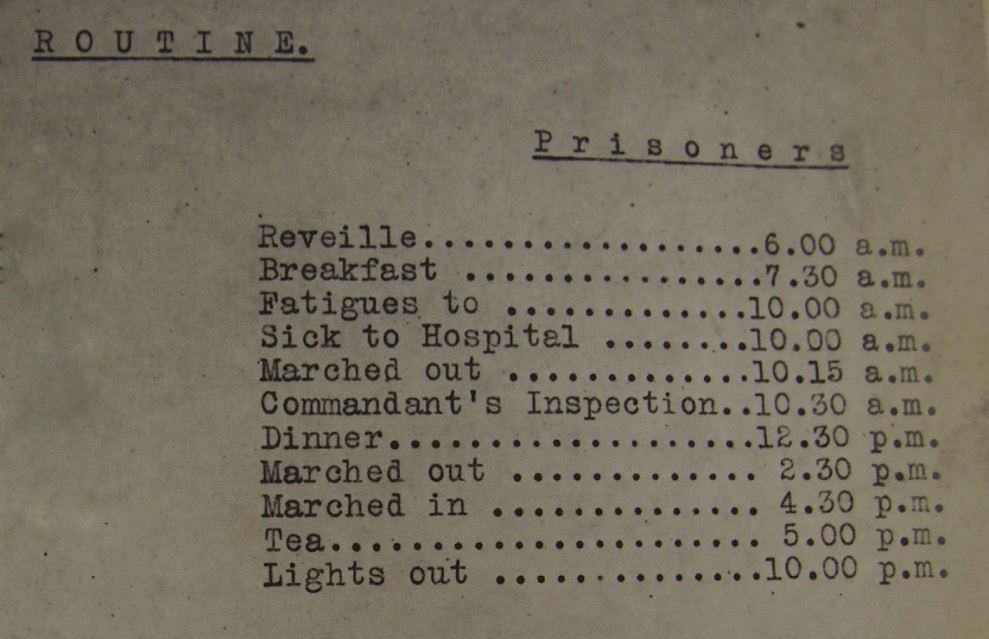

Daily routine for prisoners interned at Alexandra Palace, 1915 (catalogue reference: FO 383/33)

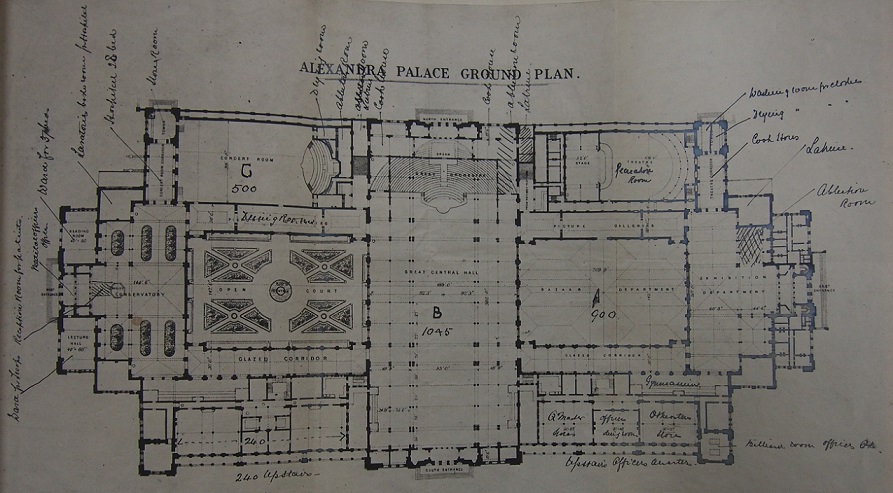

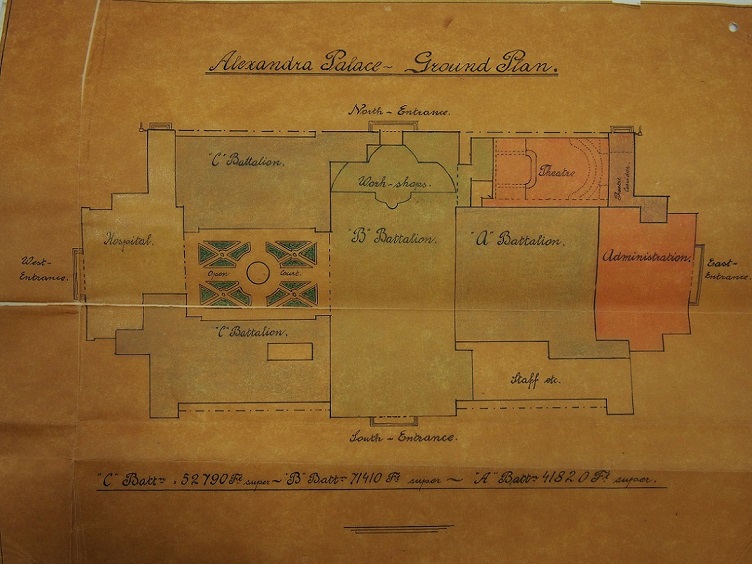

The report tells us that 1,368 prisoners were interned at Alexandra Palace back at that time and the palace was divided into three subdivisions, each to contain 1,000 people. The kitchens were described as bright, airy and clean and they were presided over by German cooks. A committee of prisoners prepared the menus which offered dishes of roast beef and vegetables, as well as mutton stew for lunch; bread pudding was served for dessert. The quantity of food prepared seemed ample to the inspector and he was told that there were always leftovers from every meal.

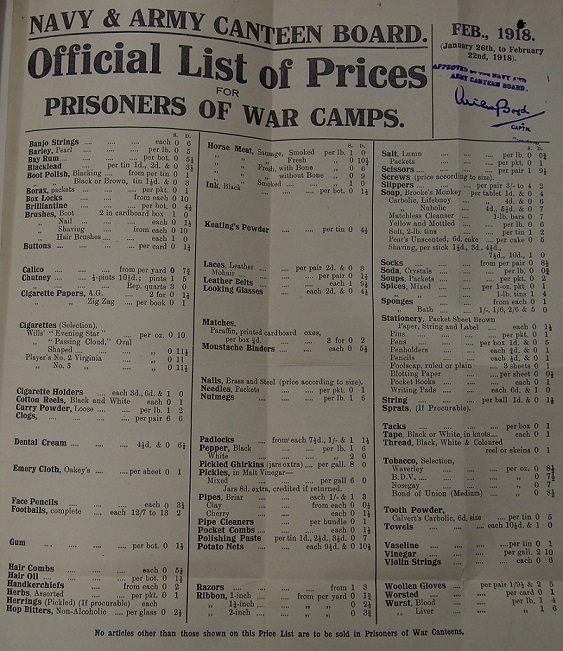

Official list of prices for Prisoners of War camps by the Navy and Army Canteen Board, 1918 (catalogue reference: FO 383/469)

A large outdoor space was allotted for exercise with a football ground and a lake where the prisoners could sail; a big gymnasium was installed for indoor activities. Besides, the men had facilities for making toys like model aeroplanes and boats.

Privacy was a privilege the prisoners had to dispense with as they slept in large halls marked ‘A’, ‘B’, and ‘C’. Each man had a raised board bed covered with a straw mattress, pillows and three blankets (FO 383/33). In addition, canteens offered ‘luxuries’ like cigarettes, horse meat, ink or socks (FO 383/469). As already noted, prisoners were allowed to spend £1 each per week, for example on these goods the canteens had in stock, from money that was sent to them – kept on deposit with the Camp Treasurer.

Visitors were also permitted, received in a reception room with a guard present; the guards were housed within the palace, too. One inspection record shows that the hospital arrangements were not yet complete on the day of the inspection, but a temporary hospital was in operation and, according to the inspector, up-to-date. The inspector stated that he spoke to the prisoners and that none of them made complaints regarding their treatment or the quality and quantity of food (FO 383/33).

How does this report sound to you? The records of civilian prisoners interned at Alexandra Palace reveal, as expected, different experiences of their confinement and shed light on their individual lives.

Alexandra Palace ground plan, 1915 (catalogue reference: FO 383/33)

‘A feeling of unrest and dissatisfaction’

Many interned civilians, contrary to the several official positive reports, made complaints about their situation. Complaints of poor hygiene and food were particularly prevalent. Throughout the war years, prisoners consistently sent appeals to the British Home Secretary or to the Embassies of neutral states against their internment and asked for improvements of their confinement or for their repatriation.

One example is the prisoner Richard Perls, who complained in May 1916 that ‘acute mental breakdown frequently occurs [among the inmates], cases of insanity result, symptoms of many illnesses appear,’ and that the ‘breaking up and ruin of mostly English-raised families’ was an unbearable hardship (FO 383/190). Two ex-prisoners of Alexandra Palace, Max Cogho and Karl Klein, testified in July 1916 that they had seen meat stamped in 1911 which was defrosted for their meals; they also complained that the sanitary arrangements in the camp were unheard of (FO 383/190).

Alexandra Palace ground plan, 1917 (catalogue reference: FO 383/469)

Another example comes from the Battalion leaders of halls ‘A’, ‘B’, and ‘C’, who sent several letters to the Army Council at the British War Office in 1918 and reported a ‘feeling of unrest and dissatisfaction in the camp’. They asked to ‘at least authorize the issue of ½ oz. of margarine per man per day because the rations were ‘barely sufficient to sustain a man,’ but their appeal was rejected (FO 383/360). Besides, the noisy environment – with so many men living together – was very difficult to bear, and the separation from their families cruelly felt (FO 383/469). The men were unable to provide for their families, many even had to ask their wives to send them food parcels.

Some prisoners even tried to escape, so unbearable did they find camp life. The 18-year old German Heinrich Evers was just one example of a prisoner who tried to escape in 1915. Unfortunately for him, he was recaptured and sentenced by a Court Martial to six months in penitentiary. He only had to serve his sentence for a little over two months, though; owing to his good conduct in prison, the remainder of his sentence had been remitted and Evers was transferred to the prison camp at Stratford (FO 383/78).

It was only in 1919, several months after the signing of the Armistice, that the prisoners were finally allowed to leave Alexandra Palace Prison Camp and were able to return home. These accounts, held by The National Archives, provide insight into some of the prisoner’s thoughts, needs and worries during their time of captivity at Alexandra Palace. The sheer numbers and statistics of official reports become meaningful personal stories once again, opening up new perspectives.

Ally Pally then and now

Alexandra Palace, 2016

Three weeks ago, I visited Alexandra Palace for the first time. It was a sunny Sunday; many families enjoyed the good weather and used the grounds of Ally Pally in the purpose for which it was built – for their enjoyment and leisure.

While I was exploring the area, a plaque, rather inconspicuous and mounted on the palace walls, suddenly caught my attention. It reminds visitors of Alexandra Palace’s past life as prison camp. The sign reads:

‘1914 – 1919 // This plaque was placed here on Sunday 4 June 2000 by members of the Anglo-German Family History Society to remember over 17,000 German and other civilian prisoners of war interned at Alexandra Palace between 1914 and 1919, in particular those who died during that period.’

Plaque by the Anglo-German Family History Society remembering over 17,000 civilian prisoners interned at Alexandra Palace between 1914 and 1919

Just like its diverse history, Alexandra Palace reveals many different and personal stories from the time of the First World War – and many still wait to be discovered.

If you wish to do more research on Alexandra Palace, please visit our website and use Discovery, our online catalogue. Alternatively, browse our image library Image Library.

You can also visit the official homepage of Alexandra Palace for more information.

Notes:

- 1. I admit that £1 in 1915 would, according to the Bank of England, nowadays cost round about £92, so this is not a fair comparison to the present but it gives you an idea of the regulations back at that time. ↩

- 2. See Janet Harris, ‘Alexandra Palace: A Hidden History’ (Stroud: The History Press, 2013), 19. ↩

- 3. See Janet Harris, ‘Alexandra Palace: A Hidden History’ (Stroud: The History Press, 2013), 46. ↩

- 4. Inspectors from Britain as well as representatives from other countries were sent to the camps, for example from America, Switzerland or Sweden. ↩

Correction. A lot of the internees weren’t allowed home after the war, but were deported to Germany and Austria.

Hi Stephen, thank you for this additional information – it’s useful to note. Lauren

My Great Grandfather was at Alexandra Palace from 1914 to 1919. Hugo Lehmann (He was German/Jewish) had an english wife and 3 children that came to visit regularly. He was not returned to his family and was deported to Germany. He was never seen again.

Indeed, including my grandfather Emil Schweiss who despite appeals to the

Home Office by my father and his wife, my grandmother, for him to stay here in their home in London, he was deported! He was at Alexandra Palce camp. Disgraceful. For years I have been endeavouring to find out what happened to him, for very sadly like many people I did not ask my father whilst he was still alive the important questions – When, where and how did he die. Where is he buried ? My quest continues.

Not all German males were interned as some who had close links to Germany worked in the British Government, for example Sigismund David Waley at the Treasury (one of three people who after the war were asked if they wanted to change their names) who changed his name (Waley was his mother’s name if I recall correctly) at the beginning of the war. You could argue that to many poor British people that £1 was a lot and maybe more than they had to survive on and certainly the margarine allowance was more than British people had on their ration allowance in the Second World War. Most internees were, I would suggest, not enemies but just had the misfortune to have links to the then country’s enemies and had been serving this country well. Given at this time many British people lived in ‘slums’ and Alexandra Palace would seem to them as ‘luxury’ by comparison.

My grandfather, Wilhelm Gottlieb Thaiss (1876-1967), was interned at Alexander Palace on 16 July 1918 and released from Frith Hill, Frimley on 26 August 1919. We understand that he was interned in 1916 at Knockaloe Camp on the Isle of Man but the ICRC in Geneva have no records of his internment there. Were any of the Germans at Knockaloe repatriated to Alexander Palace? Wilhelm emigrated to London in 1890 at age 14 to apprentice as a tailor under his uncle Jacob Heinrich Thaiss. He didn’t become naturalized until 19 November 1928. Ann Hentschel, Sarnia, Ontario, Canada.

Hi Ann, thank you for your comment. It happened on a regular basis that prisoners were transferred from Alexandra Palace to the Isle of Man and it might well be that this happened the other way round, too. Originally, Alexandra Palace had been reserved for civilian prisoners married to wives of British or Allied birth resident in the Metropolitan Police District, though. Thus, it was hoped that their families could visit them more conveniently (catalogue reference: FO 383/432).

Hi Ann. Yes the internees were transferred from Knockaloe to Alexandra Palace part way through the war when men with British families in London were switched with others from Alexandra Palace, but also after the end of the war Knockaloe internees were repatriated often via Alexandra Palace before onward repatriation/release, and later often via Frimley. If you would like us to see what else we can find please contact us http://www.knockaloe.im/page_346292.html as you may have some key snippets of information which will allow us to tell you a lot more. See also http://www.knockaloe.im

Interesting blog – thank you for sharing!

Some interesting portraits of internees are held by the Bruce Castle Museum. See some here:

http://www.20thcenturylondon.org.uk/search/site/Alexandra%20palace%20internee

My great grandfather (fathers side) Frederick Joseph Kohler was interned here, I don’t have much in the way of details but I believe he returned to Germany (he was originally from the Dortmund/Cologne areas) in exchange for POW’s, and eventually returned to London around 1920 as he had a wife and 4 children in south London (Camberwell) he eventully died there in 1958 at the grand age of 90

My grandfather was interned, I had heard, on the Isle of Man. Is there any way I can search for him and find out which camp/s he went to and when he was returned to his English family? Are there any lists anywhere? Fortunately by WWII he was considered not a danger, and he and his second wife lived with my aunt and uncle.

It’s worth thinking about the wives left to fend at home, and the effect on the children. They had no breadwinner; the neighbours might well treat them as pariahs and worse because they had married Germans, or were the children of Germans. My grandmother took her own life because of this treatment, leaving two young children. This left an indelible mark on my father, who adored her. The scars of war run long and deep for many.

Hi Mary,

Thank you for your comment, and for sharing your family’s history.

We’re unable to help with research requests on the blog, but if you go to our contact us page: http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

I hope that helps.

Nell

Thank you, Nell, I’ll give them a try.

Mary

Hornsey Historical Society has more paintings in one of its Bulletins, and other information.

The Hornsey Journal has articles on the use of the Palace for Internees, and comments on life there, and local attitudes.

Can you tell me if there were any lists of the Internees?

This was a useful article. Thank you.

We are a Registered Charity based at Knockaloe, Patrick, Isle of Man pulling together the fragmented records from all of the internees of the first world war. initially we were seeking to collate those from Knockaloe site of the largest of all of the internment camps where well over 31,000 internees spent some of the war, however as we appreciated just how many members of families were at different camps and internees often went to a number of camps we realised that we needed to collate the records of all internees regardless of the camp. We literally have thousands listed and we are still collating them in our database – to this we are adding a huge amount of information from private collections and family collections. Do contact us http://www.knockaloe.im/page_346292.html if we can help you find out more or if you have a story t share with us. See our website http://www.knockaloe.im.

Mareike – this is a great article – we should love to chat to you at some point. The National Archive records are a wonderful resource and ultimately we have so much research to do within them – I have had a great few days there. If we can assist in any way with your research or vice versa do let us know. As I mentioned above, we are a Registered Charity and to be honest we initially started this as we have so many people coming to Knockaloe to find out about where their ancestor was interned and currently there is no on-site information except a similar Anglo German Family History Society plaque to the one you show at Alexandra Palace. At the moment we provide free guided tours for descendants, ultimately we will have a Visitors Centre in the old village school where Knockaloe Camp inquests and court cases were heard (opening Spring 2018). But we already have the Database well underway with the majority of readily available internees listed which was part funded by The Centre for Hidden Histories set up by the University of Nottingham . We are totally not for profit and all time invested is 100% donated – we just feel that we need to bring the information together on the tens of thousands of men who lived in our village 100 years ago. We really appreciate the opportunity to tell people how we can help – your blog has done that. So thank you and apologies for the long comments! Alison Jones http://www.knockaloe.im

My grandfather was inturned at Alexander Palace and died there in 1918 how can I find out where he is buried.

Hi Ann,

I’m afraid we can’t help with research requests on the blog, but if you go to our ‘contact us’ page at http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

Best regards,

Liz.

Great read. My great grandfather, Friedrich Walter, was at Ally Pally as well. I knew little bits but not anywhere near the amount of detail. The contemporary paintings of the camp by George Kenners are interesting as well. Thanks for the work

My Grandfather, Johann Kaspar Hallerbach, born in Bad Hönningen on 8.7.1871, was interned at Alexandra Palace and the Isle of Man. I have a photo of him with other internees taken on the Isle of Man. He emigrated to England at the end of the 19th century. He was my Grandmother’s second husband after her first husband died at an early age. I have my Grand-

mother’s Identity Card where her British nationality has been crossed out

and replaced with German. My mother, born in 1903, Frances Anna, was the

first of 4 children. Apparently my Grandfather followed a brother to England

and I can’t find anything about this brother. I presume my Grandfather was

also deported, as there is a remark in the church records in Bad Hönningen

that he was in Cologne in 1920. I don’t know when he returned to England

but he died on 17.2.1940 aged 68. My mother had difficulty getting a job after WW1 having a German surname.

My grandfather, Charles Dobert(Dobbert) was interned during the first world war at Alexandra Palace. He was later transferred to the Isle of man. My mother always told the story that her mother would take her to see her father, she was chosen out of her sisters because she was the skinniest and her mother could hide more food on her to pass to my grandfather. This contradicts well fed?.

My Great Grandfather Friedrich Hahn (well known Bakery in Newington Green Road, Islington until 1969, now a Ladbrokes 🙁 ) was interned at Alexandra Palace – my grandfather recalled having to take food parcels to him, because they were kept short of food. In 1914/15 he had an English wife and six children aged 14 – newborn. He eventually Naturalised in 1925; my Grandfather changed his surname in 1925 from Hahn to an English one, as his future mother-in-law refused to accept her daughter ‘marrying a German’

GgF next younger brother Adam Hahn had three small children, had Naturalised in 1909, but that didn’t stop his bakers shop (Hampstead Road) being smashed up by a crowd of 6,000 (St Pancras Gazette) – his family changed their surname: he was then ‘called up’ in 1918 despite his age, into a British Army ‘German regiment’ (which was kept in UK), and had to plead to keep his new ‘English surname (letters to Home Secretary at NA, Kew)

Their next younger brother Peter was 37, a Widower with two small children. He was interned at Ax P, repatriated (International Red Cross records) June 1919 and died back in the family’s village in Germany little over a month later in July 1919. Incidentally, it is ONLY this year i.e., one hundred years later, that his descendants learned what his fate was (through a visit to the German village and coincidentally turning over Burial records at the local church).

Their youngest brother in UK, Heinrich was 26, had a toddler and new born: interned on the Admiralty requisitioned AMC Ascania, moored on the Thames (Aug 14) to house Germans. Also, interned in the former Islington workhouse. Not repatriated – that I can work out from ICRC – but went back to Germany (poss at same time with his dying brother) and died in their home village in 1947. His English wife also had to face another Internment assessment in WW2 1940 as she was still ‘married to a German’.

GGF’s brother-in-law – with English wife and four children – was interned Spalding, and ‘repatriated’. Evidently managed to return as he appears in 1939 register.

Meanwhile, Great-great Grandmother in Germany coped with all this (not seeing her eldest sons for about 35 years – they’d gone to UK as 14 years c1890s – and seeing her ‘baby’, the youngest, aged 22, off as a Kreigfreivilliger (War Volunteer): he was killed within months in Novembr 1914 at Poelkapelle, Flanders along with thousands of, mostly, 17 – 19 year old, other Kreigfreivilligers.

I have a group photo of my Great-grandfather and several other German men, taken at Alexandra Palace – I would love to know if NA would like a copy; also to know if other people might identify their relatives in it. All the men I have mentioned were part of the north-London German community and all were Bakers.

My grandfather Karl Josef Nickel, a journeyman baker, came to this country around 1897, married an English woman in 1899 and they had two sons and five daughters. He had an Eel Pie shop before being imprisoned in Alexander Palace in 1914. His eldest son lied about his age and enlisted in the London Regiment using his mother’s maiden name. My mother remembered my grandmother hiding food under her clothes when she visited my grandfather. Left to care for their three youngest children, who were frequently called ‘dirty Germans’ my grandmother was forced to move home several times and she died of breast cancer in 1917 – on the death certificate she is just described as the wife of an interned German. The following year their eldest son was killed in the second battle of the Somme. My grandfather was repatriated to Germany at the end of hostilities but he did return to care for his children, married again and died in 1952. His other son died in 1940 aboard HMS Glorious. Along with his daughter from my grandfather’s second marriage, I was fortunately able to attend the unveiling of the plaque on 4th June 2000

These comments made me feel quite emotional and sad for those who suffered misfortune through no fault of their own. The sad stories of that terrible war could fill an ocean with tears. My East End Jewish mother’s family, who had arrived in London mid 19th century, had the German or possibly Austrian name of Friedberg. They never changed it and sometimes met discrimination for being Jewish but ,as far as I know, never for their German name. There are still a few descendant Friedbergs around the South of England .

My great grandfather, Gustave Strômke (Stremke)was interned in Alexandra Palace and all anyone knew until today was that he was repatriated at some point. He was never heard from after being interned. I have today found a record of him being repatriated from Spalding Lincolnshire, presumably to somewhere in France as all the record is in French.The word on the record ‘disparu’ could mean missing or dead.Not a great deal of information, but evidence that he existed. As with many of the stories above, he left a family behind.The brother of his wife slit his own throat at the tea table at about the time the internment took place.It is hard to believe that this wasn’t somehow linked and there will, of course, have been many families in communities made up of German immigrants affected. My grand-father kept his father’s surname out of respect, so during WW2, as an infant aged school girl, the mothers of my mother’s classmates called her names when she walked home from school.Meanwhile, her father was abroad fighting for Britain. We’re a lovely lot, aren’t we?

FOR ANYONE LOOKING FOR MEMORIAL OF THOSE WHO DIED WHILST INTERNED

(Particularly Ann Bethell above – I had seen something yesterday and just spent hours re-looking and eventually found it)

ALEXANDRA PALACE AS A CONCENTRATION CAMP

Several London cemeteries feature strikingly cheap-looking memorials erected by the local authorities above the mass graves of civilian victims – mainly air raid casualties – of the twentieth-century World wars, but perhaps the most economical-looking monument of all, in the Great Northern London Cemetery in the London Borough of Barnet, is one erected by the British central government and has an inscription in German: Hier ruhen die genannten 51 deutschen Maenner die waehrend des Weltkrieges in Zivilgefangenschaft gestorben sind. (Here rest in God the named 51 German men who died during the World War in civil imprisonment.) It is the principal surviving relic of the time when, during the 1914-1918 War, Alexandra Palace was a concentration camp for male enemy aliens of military age. In the first months of the war more than 50,000 German, Austro-Hungarian and Turkish nationals resident in Britain were arrested and by the time of the Armistice in November 1918, after selective repatriations and releases, there were still 24,500 men in internment. They included, allegedly, a former colonel in the British Army, and a Church of England clergyman, as well as novelist John Galsworthy’s nephew Rudolf Sauter. Some of them were men (or the sons of men) who had come to England to avoid military service in Germany. I

And I’ve found all the details here:

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1433355

The memorial is listed which means it has some protection

My grandfather Georg Gustav Haug was interned in Alexandra Palace during WW1. He was a top class professional chef. He and others wrote a very detailed 2 page closely typed letter to David Lloyd George in 1918 begging him to investigate the dreadful quality of their rations, they do sound very bad. I can provide a scanned copy if anyone is interested.

Hilary Challis

I would love a copy of your photo. My great-uncle was there for while as well as a more distant relative. Eva Lawrence.

Read all these with interest, as my Grandfather Johann Rudolf Schriever, after being arrested was first sent to Frith Hill and then transferred to Alexander Palace. We have never found out when he was released or weather he was sent back to Germany. But the 1921 census has him unemployed in London, further it states his previous employee was a German company. So we assume he was sent back to German after release from Alexander Palace and returned to England to his family sometime before 1921. Are there any records of those that we returned to German that can be recearched?

My maternal grandfather, Eugene Weress (aka de Weress), was studying portraiture in London when WWI broke out and he was interned. First he was sent to Alexandra Palace, and then later to the Isle of Man. I have a photo of him at the IOM barracks dated 1917 but I have no other dates, as far as when he was at Alexandra and for how long. Same for Isle of Man. How can I find these dates please? Luckily he was released and eventually came home so when he married my grandmother and had my mother, I was eventually able to meet him in NYC, where they had all moved. Appreciate any leads on dates of incarceration. Thank you.

Dear Lily,

Thank you for your comment.

To ask questions relating to research, please use our live chat or online form.

We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.

PLEASE NOTE: Due to the age of this blog, no new comments will be published on it. To ask questions relating to family history or historical research, please use our live chat or online form. We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.