Truth is often much better than fiction. Some of you may have read ‘The English Patient’, or seen the film; I must confess I found both slightly boring, but some of the true stories behind the novel are much more entertaining.

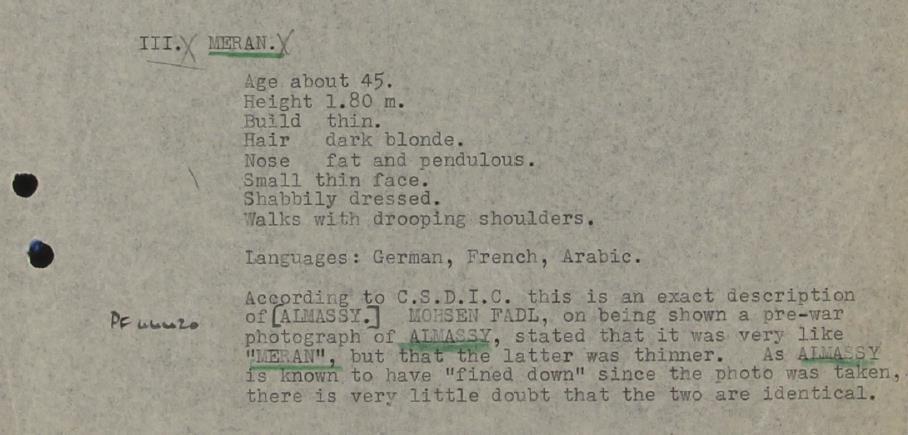

The ‘English patient’, I hate to say, wasn’t a romantic horribly-wounded-but-terribly-handsome hero figure – he was actually described as ‘very ugly’ with ‘nervous tics’, a ‘fat and pendulous’ nose, walking with ‘drooping shoulders’ and ‘shabbily dressed’. Besides, he wasn’t even English (KV 2/1463).

Description of László von Almásy (catalogue reference: KV 2/1463)

László von Almásy was a Hungarian pilot and desert explorer. He spent the 1930s driving around and flying over the Libyan Desert (that part of the Sahara that stretches between Egypt, Sudan and Libya), looking for the mythical lost oasis of Zerzura and drawing maps. Recruited by the Abwehr, the German military intelligence, at the beginning of the Second World War, Almásy was involved in one of the most interesting failures of German espionage in Egypt, which largely contributed to ‘breaking up the Egyptian 5th Column’: Operation SALAM, followed by Operation KONDOR (KV 2/1468).

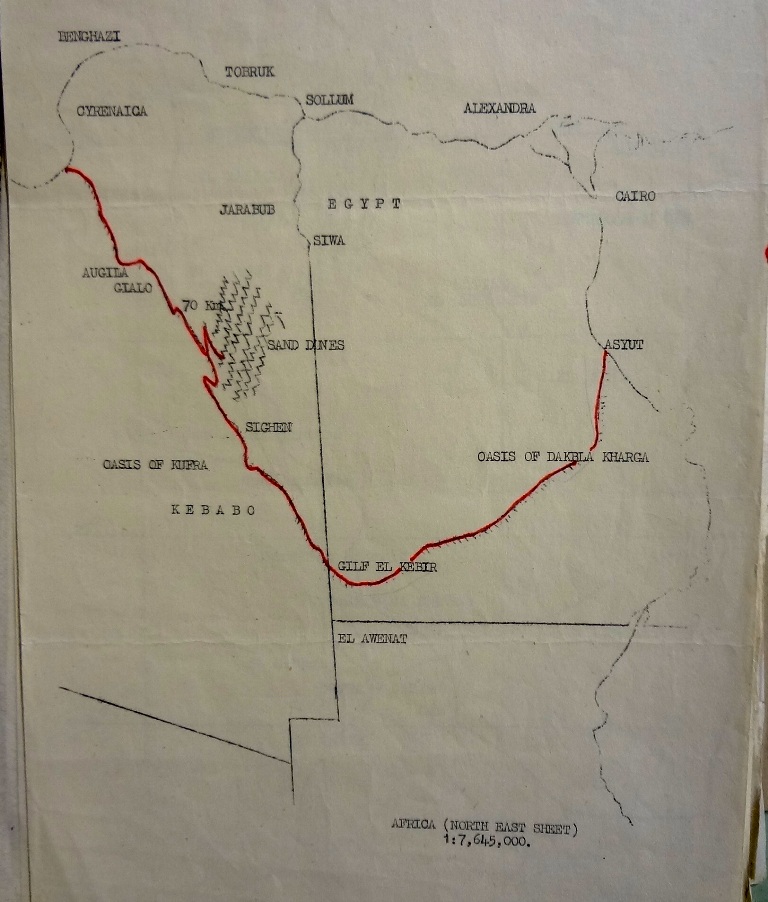

In May 1942, Almásy took the head of an expedition to drive two German agents, Johannes Eppler and Heinrich Sandstede, known as MAX and MORITZ, across the desert from the Libyan oasis of Gialo to the Egyptian town of Asyut.

From Gialo to Asyut (catalogue reference: WO 208/5520)

They left Gialo on 12 May, with a small team and 6 Ford V8 lorries. After about 70 kilometres, they hit sand dunes and had to double back. Very cautious, they avoided the very heavily garrisoned oasis of Kufra, and buried canisters of petrol and water for Almásy’s return journey. Driving on, they reached the Gilf Kebir plateau. They struggled to find the right passes, but finally uncovered the tracks of Almásy’s 1932 expedition.

About 7 kilometres from Asyut, Eppler and Sandstede left the group to continue on foot with two wireless transmitter (W/T) sets, while Almásy returned to Gialo. They quickly changed into civilian clothes, buried their uniforms and one of the W/T sets, and marked the spot. They finally arrived in Asyut in the morning of 24 May, and took a train for Cairo at 1pm. Operation SALAM was over, Operation KONDOR could begin (WO 208/5520).

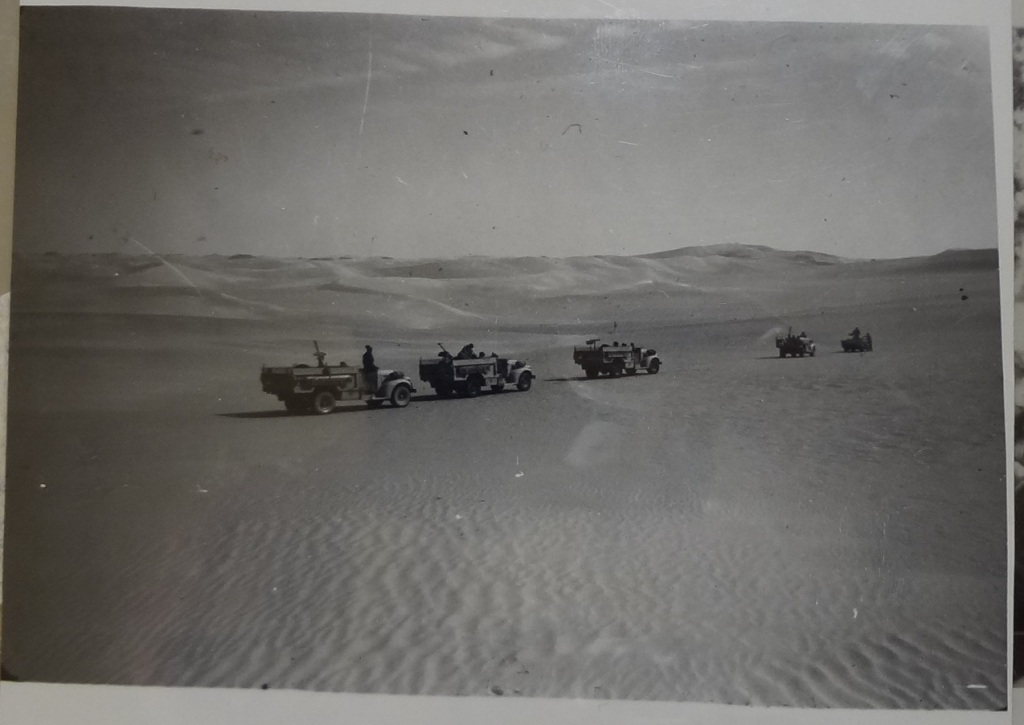

The Long Range Desert Group in the Western Desert (catalogue reference: INF 2/44)

Once in Cairo, Eppler and Sandstede had to ‘establish a wireless transmitter (…) by means of which they could send news of troop movements, etc., direct to Rommel’s HQ’ (FO 141/852). As they had also been instructed to ‘contact, by W/T or directly, certain suitably-disposed Arabs’ (KV 3/74), they started networking. Posing as Hussein Gafaar (Eppler had been raised in Egypt and spoke flawless Arabic) and Peter Muncaster, they visited ‘various places of amusement and refreshments’, such as Café Groppi or the Kit Kat Club, and ‘gradually acquired a useful entourage of pimps, money-changers and so-called friends’ (FO 141/852).

Sandstede tried to contact their base and got no reply, which he thought was due to the unsuitable location of his W/T set. They moved onto a dahabiya, a house-boat on the Nile, but still failed to establish communication (KV 2/1468). After two months, their situation had become rather desperate. According to Jenkins, the Defence Security Officer in Cairo, they ‘had spent money in profusion, had achieved nothing and could get no response to their transmissions’ (FO 141/852). Weber and Aberle, with whom they were supposed to communicate, had been captured in the desert, but Sandstede attributed his continuous failure to faulty parts. They decided to get in touch with Viktor Hauer, a German national working at the Swedish Embassy.

They needed to send a message through to Rommel’s HQ, and to get Eppler out of Egypt and back to Rommel, preferably by air, to explain their situation and ask for more money. Hauer provided a transmitter (which had conveniently been left in the basement of the Embassy), and introduced them to one Frau Amer, the German wife of an Egyptian doctor. Through Frau Amer, they met two Egyptian officers: Hassan Ezzat, from the Egyptian Air Force, and Anwar el-Sadat, from the Signals Corps (incidentally, he became President of Egypt in 1970).

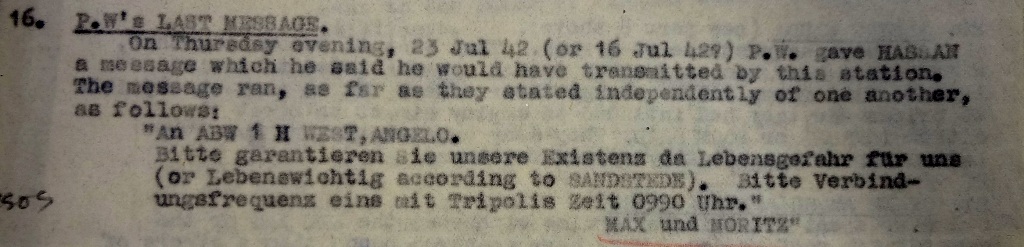

They agreed to send a short SOS message to Rommel and that Ezzat would make arrangement to fly Eppler out of Egypt. On 23 July 1942, they transmitted the following message:

‘To section 1 H West of the ABWEHR, ANGELO.

Please guarantee our existence. We are in mortal danger (or it is exceedingly urgent, according to Sandstede). Please use the wave-length No. 1 at 0900 hours Tripoli time.

MAX and MORITZ.’ (WO 208/5520)

Last message from Eppler and Sandstede, 23 July 1942 (catalogue reference: WO 208/5520)

Viktor Hauer (KV 2/1468)

Hauer, in the meantime, had been busy playing double agent. On 11 July, he warned a British agent in Cairo that he had been contacted by German spies and had agreed to help them. Jenkins therefore decided to ‘kidnap’ him so that he could be properly interrogated. Picked up on 21 July, as he was coming out of the cinema (KV 2/1467), Hauer proved ‘of assistance to British Security Authorities’ and was secretly interned in Palestine ‘for his own protection’ (KV 2/1468). His arrest and internment were actually so secret that neither Jenkins’ own police nor the Egyptians were informed (KV 2/1467).

Eppler and Sandstede were finally arrested on 24 July 1942, on their dahabiya. Initially very reluctant to cooperate, they soon decided on a full confession, and the rest of the network was arrested, including Frau Amer, Hassan Ezzat and Anwar el-Sadat. At Sadat’s house, the police found an English version of ‘Mein Kampf’ with paragraphs underlined in red, and a diary which seemed to indicate he had been sending messages to the enemy. The British Ambassador in Cairo, Miles Lampson, commented: ‘I hope the man will be shot’ (FO 141/852).

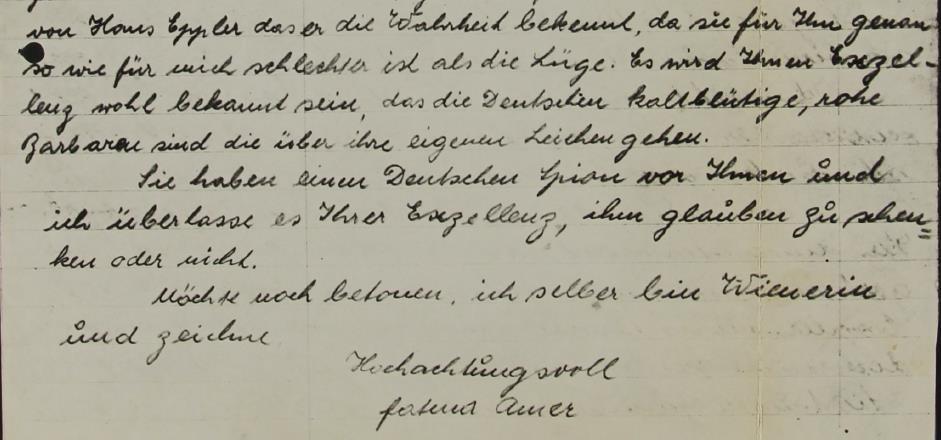

A military court was set up, and interrogations began on 12 August. Ezzat and Sadat initially denied having ever met Eppler, Sandstede and Frau Amer. Frau Amer, later described by her interrogator as ‘a most dangerous woman, a brilliant actress and a convincing liar’, kept changing her story. She eventually confessed everything in September, in a letter to the Egyptian Prime Minister, Mustafa el-Nahhas Pasha. She wrote of Eppler:

‘It may as well be known to Your Excellency that the Germans are cold-blooded, rude barbarians, they would march over their own corpses.

You have a German spy before you and I leave it to Your Excellency to believe him or not.’ (KV 2/1467)

Frau Amer to Mustafa el-Nahhas Pasha, 19 September 1942 (catalogue reference: KV 2/1467)

Ezzat and Sadat finally admitted to knowing Eppler, but denied having been actively involved in espionage activities. They both claimed that Eppler and Sandstede hoped that ‘by intriguing they [would] save their lives’ (FO 141/852). Although the Egyptian officers were definitely involved (they were discharged from the army and interned until the end of the war (KV 2/1467)), they may have had a point.

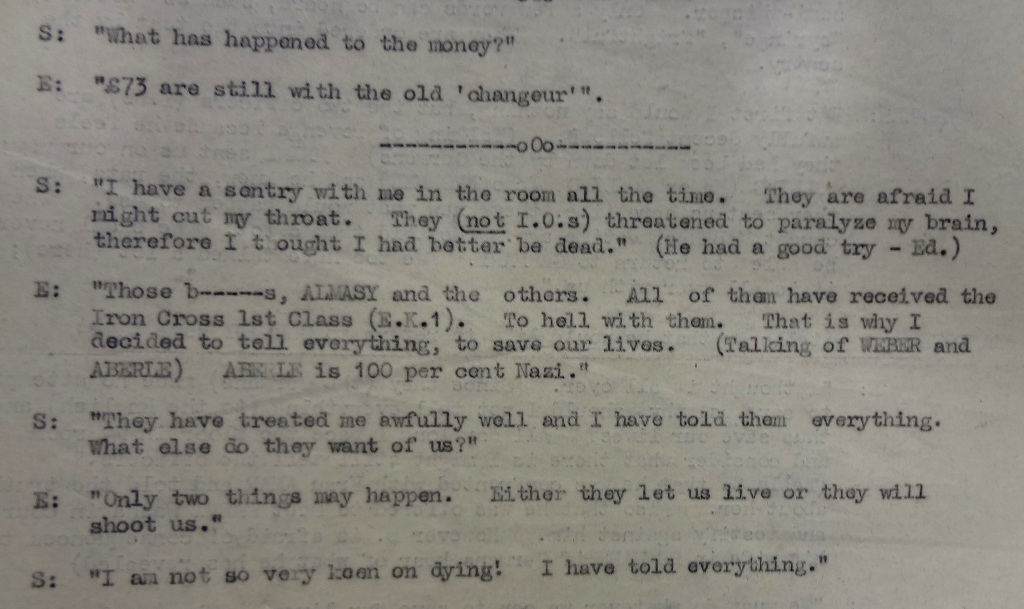

At the beginning of August 1942, Eppler and Sandstede were allowed to meet for the first time since they had been arrested. Both of them complained bitterly about their superiors and felt they had been let down. Eppler was particularly vocal. ‘Those b- – – – – – s Almásy and the others,’ he said, ‘all of them have received the Iron Cross 1st Class. To hell with them.’ He added: ‘My dead old Sandy, if they do not hang me, I say if they do not hang me, and if I ever meet Almásy again, God, how I shall beat him up.’

Focused (as anyone would be) on saving his life, Sandstede declared: ‘I’m not so keen on dying. I have told everything.’

Although they mentioned torture, they both admitted to being surprisingly well treated – and were particularly impressed by the food. Sandstede stated: ‘in comparison with the rotten stuff they serve up in the Africa Corps they have marvellous food here’ (WO 208/5520).

Conversation between Eppler and Sandstede, 04 August 1942 (catalogue reference: WO 208/5520)

In the end, Eppler never got to beat Almásy up. Having made it back to Gialo safely, Almásy then returned to Hungary and wrote a book on his war deeds.[ref]1. L. Almásy, ‘Rommel seregénél Líbiában’ (With Rommel’s Army in Libya). Stádium, 1943[/ref] After the war, he was arrested in Hungary for having worn an enemy uniform, but was eventually released. He died in Salzburg in 1951, having been appointed Director of the brand new Institute Fuad I for Desert Research (now the Egyptian Desert Research Centre, in Cairo).

László von Almásy (image: Wikimedia Commons)

And before you start wondering, he did not die of an overdose of morphine while dreaming of the woman he loved. He died of amoebic dysentery (I looked it up, it’s as unromantic as can be), and letters found in Germany showed he wasn’t interested in women.

Almásy was a brilliant explorer, pilot and cartographer, driven by his passion for the desert and its legends. He was admittedly a romantic figure in his own right, but definitely not an ‘English patient’. In the words of Murray, who wrote his obituary in the ‘Geographical Journal’, he was ‘a Nazi but a Sportsman’[ref]2. G. W. Murray, Obituary. ‘The Geographical Journal’, vol. 117, No. 2 (Jun., 1951). p. 254[/ref]

Several sources have picked up the comment identifying MERAN as Almasy in KV 2/1463, however this was the case of a mistaken identity, Graf von Meran was clearly revealed to be an SD officer in the interrogation reports of Thomas Ludwig (KV 2/2652), and the Pyramid Organisaton was entirely an SD affair with no connections to Almásy or any Abwehr operation. Please correct this misinformation (including the physical descrition, which is completely incorreft). This error was already pointed out in 2013 (Gross et.al. Operation SALAM, Bellevlle, Munchen, p. 66).