The final episode of the TV drama series, Versailles, which was shown last night on BBC Two, gave centre stage to the traumatic death of Henriette, the wife of Louis XIV’s brother, Philippe, Duke of Orléans.

The production as a whole veers between fact and fiction, but elements of the depiction of Henriette’s death have been based upon eyewitness accounts. It might be supposed such accounts would be found only in archives in France, but the extensive early modern diplomatic correspondence held by The National Archives in the UK includes many references to the loss of this princess.

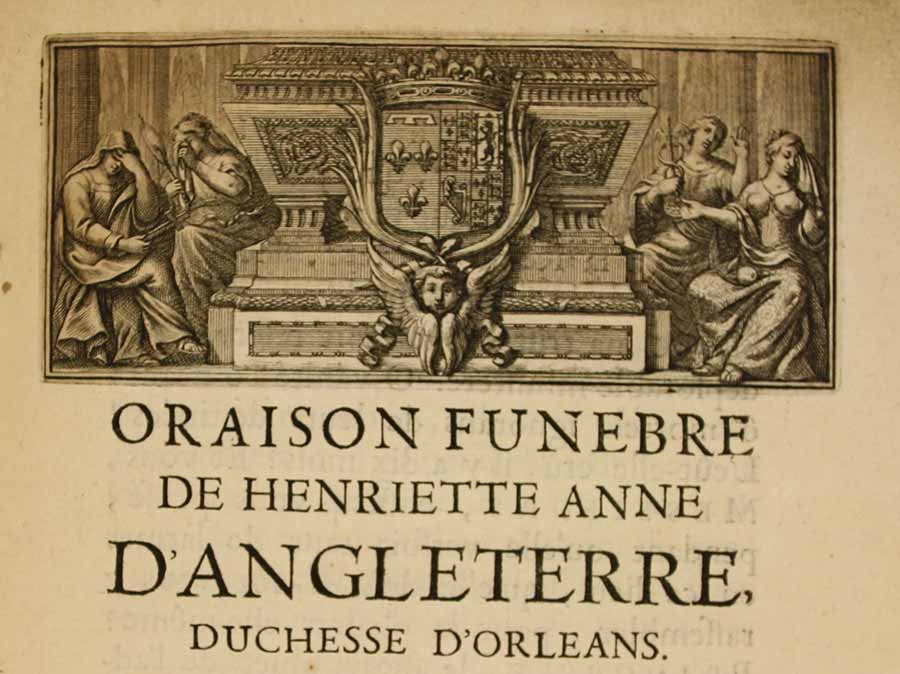

State Papers, Gazettes and Pamphlets, France: the oration given at the funeral of Henriette on 21 August was published as a pamphlet in 1670 (catalogue reference: SP 117/696)

Henriette was the daughter of Charles I, born in Exeter in 1644. Smuggled out of England two years later, she was brought up at the French court. The restoration of her brother, Charles II, to the English throne in 1660 raised her standing in the European royal marriage market, resulting in her marriage to Philippe in 1661. The young couple’s high status at the French court was underlined by the simplicity of their titles – ‘Monsieur’ and ‘Madame’.

Madame had close and affectionate relationships with her brother, Charles II, and with her brother-in-law, Louis XIV, although there is no evidence that she had an affair with the latter as suggested in the TV series. In May 1670, because of the trust shown in her by both monarchs, she travelled to England to sign the secret Treaty of Dover on behalf of Louis; secret primarily because of Charles’s controversial commitment in it to return his country to Catholicism. Only a few weeks later, on 29 June 1670, Madame was dead, aged just 26.[ref]1. At this date, France followed the Gregorian calendar (New Style) while England still followed the Julian calendar (Old Style). As a result dates in the two countries were recorded as being 10 days apart. Therefore 29 June 1670 in France was the same day as 19 June 1670 in England.[/ref]

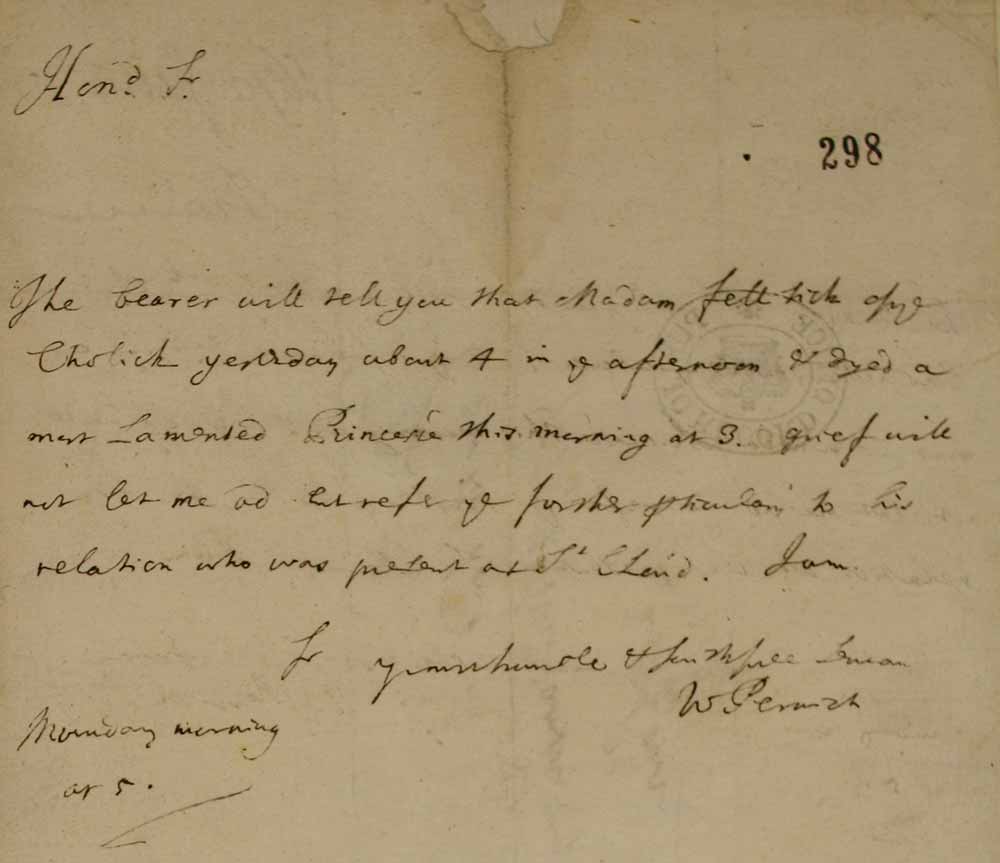

The news arrived in England three days later. [ref]2. See newsletter to Gilbert Staplehill, 27 June 1670, which states ‘On the 22nd, at 10 a.m., arrived an express from Paris, with tidings of the sudden death of Madame, his Majesty’s sister’ in State Papers Domestic, Charles II: SP 29/276, f.253[/ref] This short letter from William Perwich, English agent in France, was written to Joseph Williamson in the Secretary of State’s office just two hours after the event.

‘…Madam fell sick of the Cholick yesterday about 4 in the afternoon & dyed a most Lamented Princesse this morning at 3. Grief will not let me ad[d]…’

The letter has been roughly torn around the seal, suggesting it was opened hurriedly by its recipient.

State Papers France: letter from William Perwich announcing the death of Madame, 29 June 1670 New Style (catalogue reference: SP 78/129, f.298)

Perwich was able to send a fuller account ‘on this most deplorable subject’ a couple of days later.[ref]3. 1 July 1670 New Style, SP 78/129, f.279[/ref]

‘On Thursday Last Madam founde herselfe a little indisposed… on Sunday morning she declared she was not well without knowing what visible distemper indisposed her. She dined very well, … till 4 Clock in the afternoone when finding herselfe hott within, she drank 2 or 3 glasses of Juice of Chicoris, imediatly whereupon finding a merveillous alteration all over She cried out She was poyson’d chang’d her Colour in a moment, became blackish & yellow, hollow & the very simptomes of death appeared in her face…. Poor Princesse all Along she cryed out that she was in great anguish & paine desiring to be dissolved. The King was by her almost to the Last breath. About 12 Clock the Sacrament was administred unto her, at 2, the extreme Unction & near three this most excellent Princesse gaue up the Ghost.’

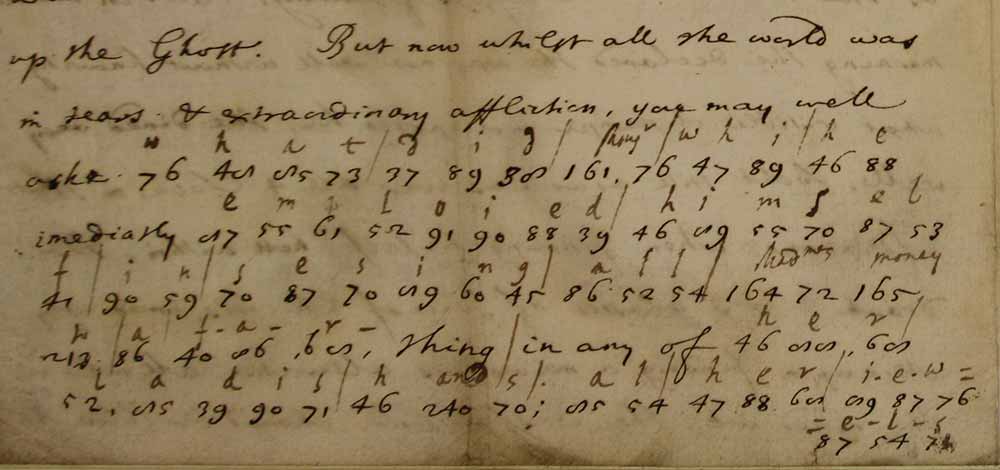

Perwich’s report at this point changes into cipher. It was commonplace for diplomatic correspondence to be intercepted by the host government, so more sensitive matters were written in a code, usually numerical, to which only the writer and the recipient had a key. Fortunately, the translation of the cipher has been added to the original letter, so we can read the following:

‘But now whilst all the world was in tears & extraordinary affliction, you may well aske what/did/Monsr/whi/he imediatly emploied/himself/in/sesing/all/Madmes money/to/a/f-a-r-thing in any of her/ladis/hands/.al/her/i-e-w=e-l-s & imediatly hastned/to Paris & tumble over her/papers/al/the people/belieue/s hee was [279 – untranslated] poisond’

[…what did Monsieur? Why, he immediately employed himself in seizing all Madame’s money to a farthing in any of her ladies’ hands [and] all her jewels and immediately hastened to Paris and tumbled over her papers. All the people believe she was .. poisoned.]

State Papers France: extract in cipher from letter from William Perwich dated 1 July 1670 New Style (catalogue reference: SP 78/129, f.279)

This impression of Henriette’s bereaved husband could not be more different than that given, rather poetically, in the report of Francis Vernon, another English agent in France:

‘Mons[ieu]r is at Ruelle there to walke in the Shades of melancholy’

State Papers France: extract from letter from Francis Vernon dated 12 July 1670 New Style (catalogue reference: SP 78/130, f.5)

The grief of the King of France was recorded in a letter to the French ambassador in England. [ref] 4. Translated copy of the letter from De Lionne to Colbert de Croissy dated 1 July 1670 New Style in SP 78/129, f.280[/ref] An observer at the death witnessed:

‘…the King who was there present and went not thence till this Princesse was ready to Expire… what marques of tendernesse and affection passed reciprocally between them how many teares it cast his Ma[jes]ty both in the time of her illnes and since the losse of her…’

The suspicion that Madame had been poisoned was widespread and the King acted quickly to stem the rumours. A post mortem was carried out with multiple physicians present and over 100 observers.[ref] 5. Two post mortem reports can be found among the State Papers France in SP 78/129, ff.276-77[/ref] Accounts agree that an ‘insupportable’ smell was produced when the body was cut open, that the liver was very diseased and the intestines gangrenous. Modern research provides a diagnosis of acute peritonitis caused by the perforation of a duodenal ulcer.[ref] 6. John Miller, ‘Henriette Anne, Princess, duchess of Orléans (1644–1670)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/12946, accessed 9 Aug 2016][/ref]

Madame’s final resting places were noted in a further report by Francis Vernon.[ref] 7. 5 July 1670 New Style, SP 78/129, f.295[/ref] The English princess was to remain in France in perpetuity.

‘…her heart was transported from St Clou to Val de grace on Wednesday night last attended by Madame la Princesse & by severall Coaches of Persons of Quality by torch light w[i]th a very mournefull solemnity. Her body goes to St Denis butt her heart is interred at Val de grace by Vertue of a promise shee had made to those Nuns in her life time.’

[…] article posted by the National Archive last Thursday covers another interesting crypto document from this collection: a partially […]