‘King John was not a good man’; so said A.A.Milne in a collection of poetry aimed at six year olds – and so generations of children have learnt this basic ‘fact’ about King John almost before they were old enough to go to school. 1

A.A. Milne was following in a long line of critics of the Angevin king. As far back as the 1230s, the chronicler Matthew Paris wrote, ‘Foul as Hell is, it is made fouler by the presence of King John’.

Does King John deserve his awful reputation? In many ways he probably does. But even a murderous, capricious, tyrannical failure of a monarch has to have his good points – and anyone who has ever carried out research using documents held at The National Archives may well have cause to thank him.

Why? Because for all his flaws, King John was an assiduous administrator. He was very keen on filing, and it is the filing system that seems to have originated in his reign that formed the backbone of the recordkeeping systems of English (and later British) royal government for centuries. They gradually evolved into the vast and varied collections of public records that are today in the safekeeping of The National Archives. 2 So, on the 800th anniversary of his death, it seemed appropriate to remember his importance to our organisation.

This is not to say that kings before John had never kept records. There is evidence that Anglo-Saxon kings had archives of their written documents, and we know that the 12th century Exchequer (the royal finance office) kept annual records of accounts called pipe rolls; the earliest surviving pipe roll (though not the earliest to be created) dates from 1130, and there is a nearly unbroken series from 1156 until the 19th century. 3 We should perhaps not be surprised that the desire to keep track of royal finances meant the Exchequer led the way in terms of recordkeeping!

But it seems that it was not until 1199, after the accession of King John, that the royal Chancery, the writing office of royal government, started systematically preserving the many hundreds of letters that it issued in the king’s name every year. The letters despatched from Chancery covered a great variety of subjects and were effectively the means used by royal government to get stuff done. They range from great solemn charters making grants in perpetuity to tiny writs covering the nitty gritty of local business.

Three of the earliest Chancery rolls (catalogue reference: C53/1, C54/1, C66/1) unrolled to the show the titles added to them in the late 18th century

By the time that King John came to the throne the Chancery was already well established, but the surviving evidence suggests that it did not have a methodical system of keeping track of the letters it sent out. This meant that over time it was difficult for the king and his officials to be sure of what had happened in the past – what grants had been made, what orders had been issued and so on.

This all seems to have changed under King John: it is from his reign that the first of the great series that we now call Chancery rolls survive. The Chancery rolls are great rolls of parchment onto which clerks entered copies of the letters that were being sent out – a process of recordkeeping called ‘enrolment’. For want of any evidence of earlier rolls, it has widely been argued that they must have originated in John’s reign. 4

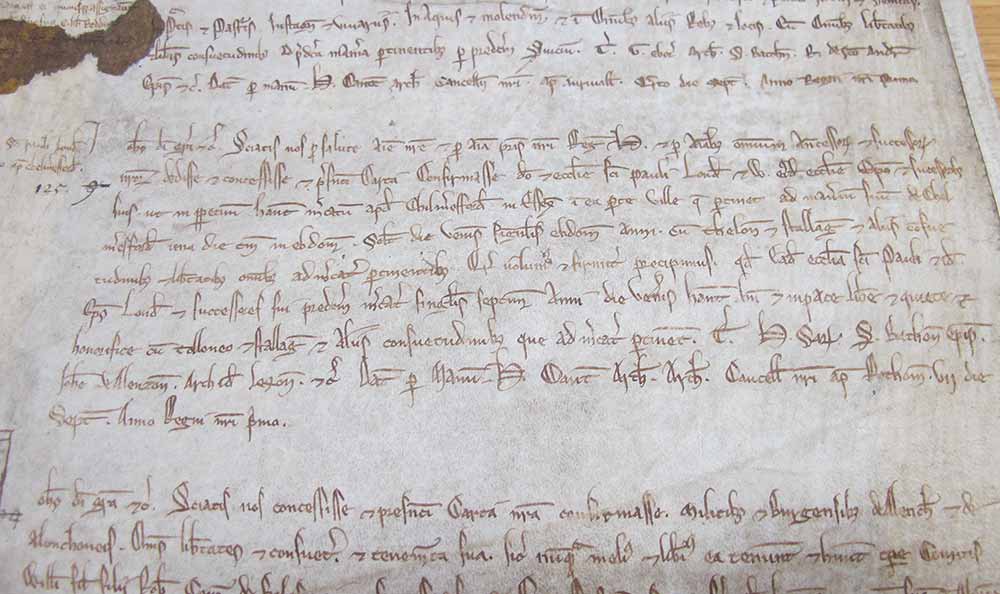

Entry on the first surviving charter roll recording the grant to St Paul’s London and William Bishop of London of a fair at Chelmsford in Essex (catalogue reference: C 53/1)

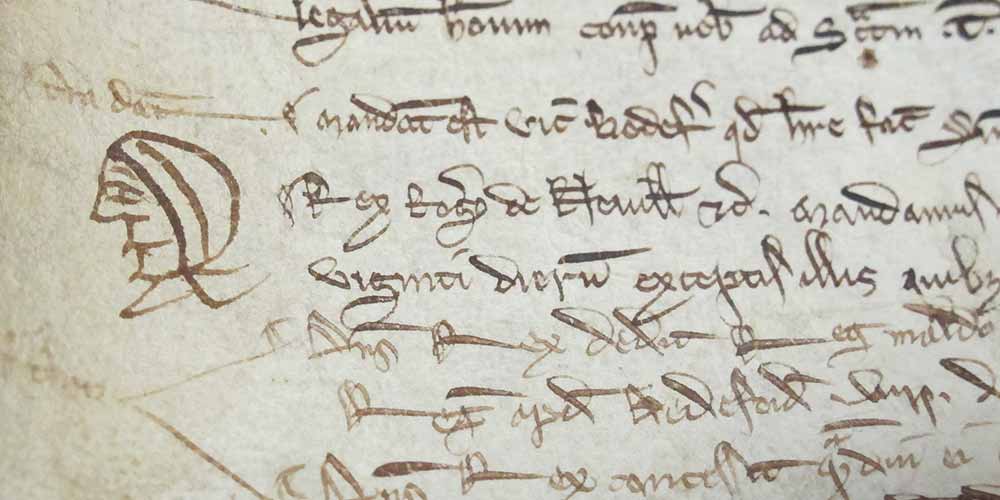

The rolls are functional rather than pretty. They were kept primarily to benefit the king and his successors: anyone claiming to have been granted something by the king could now have their claim checked against the official record. Parchment was expensive so the clerks wrote in tiny writing, using heavily abbreviated Latin (the language of government of the time). There are no colourful inks or beautiful illuminations – though occasionally there are entertaining doodles by bored clerks! While they may not be much to look at, these rolls give us an amazing and detailed record of the operation of royal government from the reign of King John onward.

Marginal doodle on the close roll 18 John, 1216 (catalogue reference: C 54/14)

Letters were sorted by type, and different letters were enrolled in different places. This probably served to solidify and codify the different types of letter issued by the Chancery – by the middle of John’s reign there were different rolls to record charters, letters patent, letters close and fines. 5

Together, these rolls give an outstanding picture of what royal government did, how it did it, and how it was paid for. It is often possible to find a grant made to an individual on the charter roll (for the most solemn grants, for example the right to hold a market) or on the patent roll (for less solemn grants, for example a one-off gift), and then on the relevant close roll to find the instructions sent to the local sheriff to ensure that the terms of the grant were carried out. On the fine roll one can often find the record of the payment offered to the king to secure a particular grant in the first place (royal favour did not always come cheap).

Although the various series of enrolments changed over time and new series were added as bureaucracy developed, this system of enrolling records of business remained at the heart of royal government for centuries.

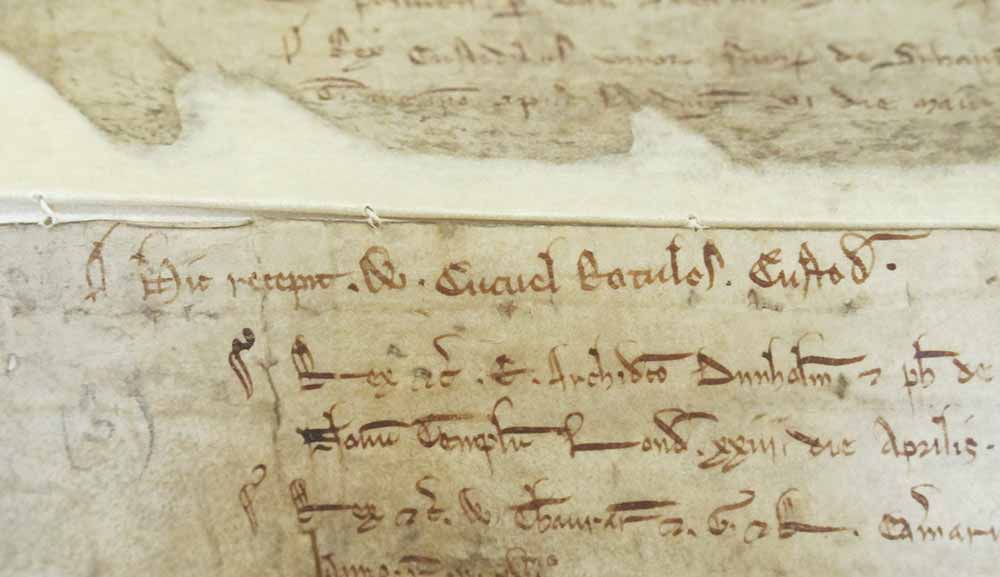

Equally importantly, King John and his officials around him were not just careful to enrol records, but to preserve the rolls themselves. The Chancery itself travelled with John, who was frequently on the move, and many of its records travelled with them. However, the inconvenience (indeed the sheer weight) of carrying such a lot of records must have been considerable, and it seems that records were regularly sent to a fixed location for safekeeping. As early as 1215, the close roll mentions one William Cucuel receiving the rolls so that he should look after them.

The first mention of a named individual (W Cucuel) looking after the rolls, from close roll 16 John part 2 (catalogue reference: C 54/10)

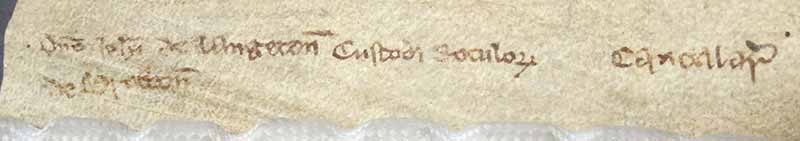

We know little else about the arrangements made for archiving the rolls until the reign of John’s son, Henry III, who arranged for them to have a permanent home in the domus conversorum, the house for converted Jews on what is now called Chancery Lane. Then in the reign of Henry III’s son, Edward I, a patent roll refers to one John Langton as ‘keeper of the rolls of the Chancery’. It was from these little acorns that centuries later the great Public Record Office would grow!

Mention of John Langton ‘keeper of the rolls of the Chancery’ on the patent roll 14 Edward I (catalogue reference: C 66/105)

We cannot say for certain that these innovations were down to King John. He was surrounded by able officials, in particular the Chancellor, Hubert Walter, and as mentioned systematic record keeping had begun in the royal Exchequer in the reign of John’s great-grandfather, Henry I. Further, John’s court was not alone in these efforts to make and preserve written records; other European courts had their own systems of recordkeeping, although the system of Chancery enrolments was earlier and more comprehensive than the attempts at archiving of neighbouring countries in Europe.

Having said that, we should remember that medieval government was centred on the person of the king. Even if John was not the driving force (and he may have been), he would certainly have had personal knowledge and understanding of the system of recordkeeping that was developing in his Chancery.

So was John a Bad King? Almost undoubtedly. Indeed, his rolls contain much of the evidence against him. We can see for ourselves in the fine rolls, for example, the extortionate sums of money that some aristocratic widows had to pay to John in order to avoid being forced to remarry – an issue that was addressed directly in Magna Carta. But the rolls themselves are a gift of immeasurable value to anyone wishing to study medieval history, and the tradition of careful recordkeeping and of the preservation of those records that stems from the reign of King John is at the heart of The National Archives today.

Notes:

- 1. Quote from King John’s Christmas, in A.A.Milne, ‘Now We Are Six’ (First edn., London, 1927). ↩

- 2. Little, if anything, in this blog is an original idea. For a fuller and more nuanced discussion of the beginnings of Chancery enrolments, see N.Vincent, ‘Why 1199? Bureaucracy and Enrolment Under John and his Contemporaries’ in ‘English Government in the Thirteenth Century’, ed. A.Jobson (Woodbridge, 2004), pp.17-48; D.A.Carpenter, ‘”In Testimonium Factorum Brevium”: The Beginnings of English Chancery Rolls’ in ‘Records, Administration and Aristocratic Society in the Anglo-Norman Realm’, ed. N.Vincent (Woodbridge, 2009), pp.1-28. It should be noted that Carpenter argues that systematic Chancery enrolment started much earlier than the reign of John. On King John’s life and reign more generally, see S.D.Church, ‘King John’ (Macmillan, 2015). ↩

- 3. Many of the medieval pipe rolls, including the earliest roll, have been published by the Pipe Roll Society. The original rolls are in the series E 372. ↩

- 4. This orthodoxy is not unquestioned – see note 1. ↩

- 5. Many of the rolls dating from the medieval period have been published in printed calendars which are available at The National Archives and in good reference libraries. ↩

Interesting item bringing King John to life & showing his good & bad qualities.

This is a delightfully clear summary of King John’s method of administering the country, and dispatching his instructions. I found the following paragraph particularly clear and helpful.

Together, these rolls give an outstanding picture of what royal government did, how it did it, and how it was paid for. It is often possible to find a grant made to an individual on the charter roll (for the most solemn grants, for example the right to hold a market) or on the patent roll (for less solemn grants, for example a one-off gift), and then on the relevant close roll to find the instructions sent to the local sheriff to ensure that the terms of the grant were carried out. On the fine roll one can often find the record of the payment offered to the king to secure a particular grant in the first place (royal favour did not always come cheap).

Real stuff/excellent research!

How were records of battles taken in such detail where historians can confidently say today who moved what soldiers where and how the battle played out?

Assuming that you are thinking about medieval battles, descriptions of battles are usually found in chronicle sources rather than the sorts of goverment records that we hold here at The National Archives. Chroniclers got their information from a range of sources – some (such as Roger of Howden) were based at the royal court and therefore had first hand access to leading figures who had been on the battlefield, others (such as Matthew Paris) were based at important religious houses where there would have been a steady stream of well-informed visitors and would also have exchanged correspondence and news with other houses, some (such as the Chandos Herald) were soldiers themselves. These chronicles can be used in conjunction with the documentary sources held here and elsewhere (such as accounts for soldiers’ wages and payments for military equipment) and of course with archaeological evidence found at the sites of battles. Historians writing in detail about particular battles will generally provide references to the source material which they are using. Of course, there is inevitably some degree of interpretation of evidence, and historians do not always agree about exactly how and where a battle was played out.

You can find further details on some of the records held here and suggestions for further reading in our research guide on pre-modern soldiers: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/medieval-early-modern-soldiers/

I appreciate this simple and clear article. When I try to translate the term “keeper of the rolls” into the medieval Spanish context, I have doubts if it would correspond to a “custos chartarum” (Latin) member of the royal chancery or to another office or function. Thank you.