Last month I wrote a blog introducing the work being done by a team of volunteers who are cataloguing record series HO 17, criminal petitions for mercy. These records date from the early 19th century and contain petitions and other papers submitted to the Home Office by convicts and their families seeking a reduction of sentence. Many of the petitions include information which gives you a sense of what an individual was like: from medical complaints to what they did in the evening, details about family life to patterns of work, we can glean much from the alibis, justifications and pleas of the petitions. These insights into a convict’s life, their hopes and fears can be very moving and I frequently find myself searching through a petition for some clue as to how the Home Office responded – will I find the annotation ‘remission prepared’ or the all too common ‘nil’?

Great Expectations, ‘You young dog’, said the man. Pip and Magwitch on the marshes, by John McLenan (Harper’s Weekly Illustrations 1860)

One such case which inspired me to take a closer look was that of James Hawkins, an escaped (and repeat) transportee whose petition crops up in HO 17/68. For me, escaped transportees have always called to mind Dickens’ Magwitch, ‘a fearful man, all in coarse gray, with a great iron on his leg. A man with no hat, and with broken shoes, and with an old rag tied round his head. A man who had been soaked in water, and smothered in mud, and lamed by stones, and cut by flints, and stung by nettles, and torn by briars; who limped, and shivered, and glared, and growled’. 1 Now, I’m fully aware that Hawkins was probably nothing like Magwitch, but his experience certainly sounds like something out of a novel. Using his petition in HO 17 alongside trial records at the Old Bailey, contemporary newspaper reports and further Home Office files, we can trace his desperate attempts to evade capture and to return to his wife and family in England.

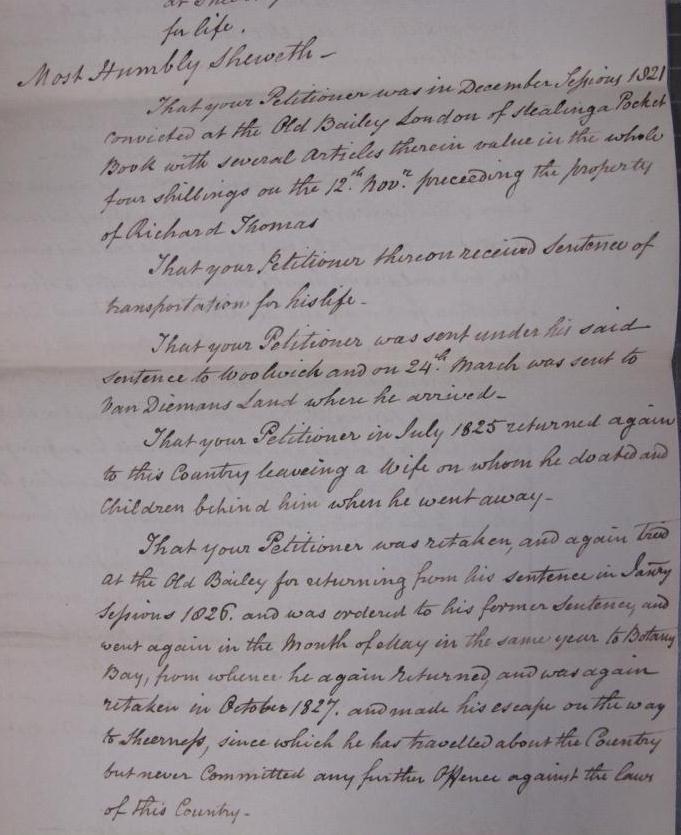

In 1821, aged 20, Hawkins was convicted at the Old Bailey for pocket-picking and sentenced to transportation for life. According to his petition the total value of the goods he stole came to less than four shillings (according to The National Archives’ currency converter this is just over £8 in 2005’s money). The records of his trial, which can be found online at www.oldbaileyonline.org, confirm that he stole a pocket-book, a silver rule, a pair of diamond tongs and an almanac from one Richard Thomas, picking his pocket in the pit of Drury Lane theatre. 2 Convict transportation registers in HO 11/4 confirm that Hawkins was swiftly sent to Van Diemen’s Land on the Prince of Orange transport ship in March 1822. 3 So far, so unremarkable, but Hawkins was not a man who could be so easily dealt with.

The 1826 convict muster for Tasmania in HO 10/46 reveals that Hawkins absconded on 13 October 1823. In his petition, Hawkins admits that he returned to England in July 1825, ‘having a wife on whom he doted and children behind him when he went away’. We don’t know how Hawkins made it back to London but unfortunately for James and his family, he did not elude the authorities for long and was arrested for being at large in St Martins in the Fields in December that year. On 14 January 1826 he was convicted at the Old Bailey for returning from transportation and sentenced to death. His sentence was commuted and on 10 May 1826 Hawkins sailed for New South Wales on the Marquis of Huntley (HO 11/6).

However, Hawkins was not a man to accept his fate and again he escaped and returned to England. Having made it all the way home he was again found and arrested in October 1827. That month Hawkins was again sentenced to death at the Old Bailey for returning from transportation. His sentence was commuted and Hawkins was again looking at spending the rest of his life banished ‘beyond the seas’.

On his way from Newgate to the hulks at Sheerness where he would await transportation, Hawkins made another break for freedom. While Hawkins might have become something of a master escape artist, he was not so good at evading detection. On 19 August 1828 he was arrested in Liverpool and sent to the convict hulk Retribution where he wrote his petition. Hawkins does not explain how he escaped or how he returned from Australia (twice), he only writes that he experienced ‘the greatest hardships, difficulties, wants and hazards’. His motivation, he writes, was his devotion to his wife and children:

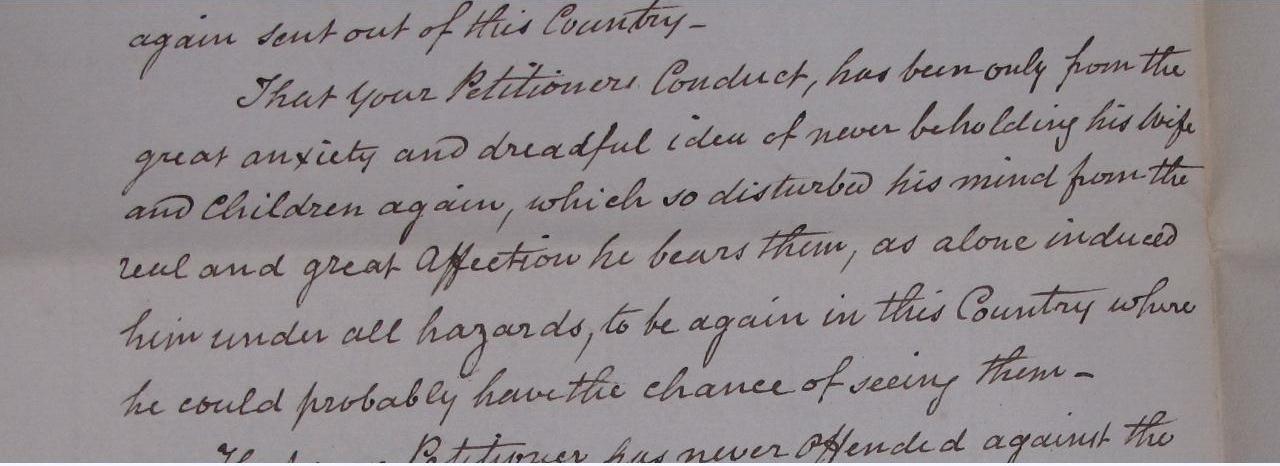

‘your petitioner’s conduct, has been only from the great anxiety and dreadful idea of never beholding his wife and children again, which so disturbed his mind from the real and great affection he bears them, as alone induced him under all hazards, to be again in this country where he could probably have the chance of seeing them.’

He claims that he is contrite, that apart from his escape(s), his first conviction was the only time he has committed a crime, and that should he be allowed to stay in England, he would not reoffend.

Not terribly surprisingly, his petition is unsuccessful and Hawkins was finally put on the transport ship the Mellish in November 1828, destined, once again, for New South Wales (HO 11/6). While we now lose sight of Hawkins in HO 17, the trail does not end here and Hawkins had one last trick up his sleeve. On 13 December 1828 the Morning Chronicle ran the following report on James Hawkins:

‘about dusk on the evening of the 8th inst., as the vessel was sailing through the Needles, he slipped his irons, and lowering himself from a port-hole, cut the hawser of a small boat, and rowed ashore to the Isle of Wight. The boat and himself were soon missed, and an immediate search was made through the Isle of Wight, but he was not found.’

The Derby Mercury on 31 December 1828 reports that Hawkins was thought drowned, and certainly the surgeon’s log for the Mellish in ADM 101/53/1 reports poor weather off the English coast delaying the ship’s departure. I haven’t been able to find any further trace of Hawkins in our records, and perhaps he did perish off the coast of the Isle of Wight, but having read his story in his own words in HO 17, it is hard not to have a sneaking admiration for a man who twice returned from the other side of the world to be near his wife and children and to hope that, after all his adventures, he finally made his way home.

Hello,

I read with interest your story on James. My 3 x great grandmother Frances Hawkins had a brother James. Family legend had him escaping several times from Australia. In the story I was told as a child he was lost at sea off the Cape of Good Hope. Thank you for confirming his story.

Hi Samantha, I have just come across your reply to Briony, while bringing up some old family names browsing on the net. Frances hawkins is also my 3x great grandmother, her daughter Mary Ann Dixon, whom she had before coming to Australia is my greatgrandmother. She also was convicted of shoplifting and was shipped to Tasmania where she married my greatgrandfather, Frederick Foster. It would be great if you come from this side of the family, but I guess you are more likely to be from the Gavenlock side.Regards, Hugh.

There is an interesting article in “The Hobart Town Courier” for 5 December 1829. This suggests that Hawkins is back in VDL. It also gives a sense of him as a career criminal by looking at his record before his various appearances at the Old Bailey. It confirms as well the statements in the British press that he was associated with pugilism and the sporting underworld more generally. I am not going to follow up this article as I am not a family historian. My interest in Hawkins is in the way in which certain sections of the press, perhaps notably “The Standard”, tried to fashion him into a folk hero – escapologist, loner rather than member of a gang, involved in crimes against the rich rather than his own kind etc etc. Thanks for info about his petition.