The recent passing of the eminent historian Professor Eric Hobsbawm precipitated a flurry of tributes acclaiming his qualities as a scholar and writer, as a literary and academic giant, and as an engaging conversationalist. And these tributes came from across the ideological divide, for it seems as though it is not possible to talk about Hobsbawm’s writing without talking about his Marxism. Indeed, when his own texts form a dialectic – from The Age of Revolution (1962) to The Age of Extremes (1994) – the political dimension of his view of history was never obviously repressed. A selection of files found amongst our records relating to Professor Hobsbawm show that the UK Government of the late 1960s found it difficult to look past his politics too.

‘Eric Hobsbawm, the Marxist philosopher and historian – FCO 61/581

April 1970 marked the centenary of the birth of Vladimir Lenin, prime theorist behind the October Revolution in Russia in 1917 and first leader of the USSR in the early 1920s. Accordingly, UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) decided to hold a symposium to celebrate his ‘great contribution to the development of education, science, and culture,’ to be held in Finland in April.

Initially the UK Government felt it inappropriate that such a symposium should exist as Lenin was such an obviously important political figure – indeed, British representatives at UNESCO abstained from the vote agreeing the symposium should take place – and we can follow discussion behind the scenes of the government during 1969 in the files FCO 61/581 and FCO 61/750. These files detail correspondence between the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), the Ministry of Overseas Development (ODM) – you can follow the history of the ODM on our Foreign Affairs timeline – and UNESCO itself.

The main thread throughout the two files is an ongoing discussion regarding which senior academic should be invited to represent Britain at the symposium. Early suggestions included academics with expertise in Russian history who would challenge the ‘strictly orthodox’ view government officials assumed would be given, and feared would be printed on UN headed paper. UNESCO, though, replied with the suggestion of Sir Isiah Berlin, the intellectual heavyweight at Oxford, and Maurice Dobb of Cambridge.

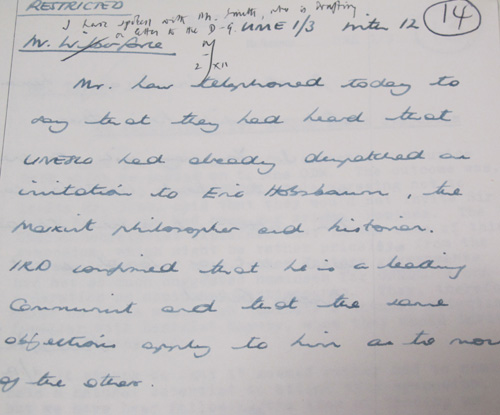

The Government’s concern about a leftist academic being chosen as the British representative (Dobb was described as ‘a Leninist’) continued as alternative suggestions were made, by both the FCO and UNESCO. As the discussions continued though, it emerged that UNESCO had approached Eric Hobsbawm, leading to an FCO official stating he is ‘a leading Communist and that the same objections apply to him as to most of the others’ and suggested a formal protest be made to the Director-General of UNESCO.

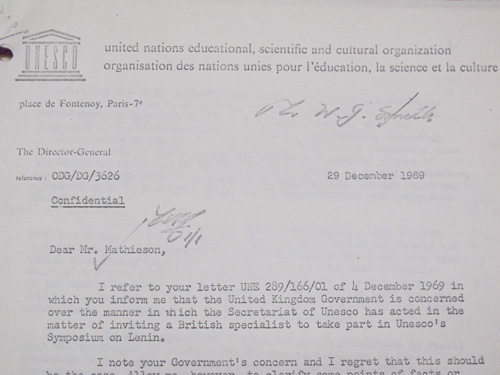

Unfortunately for the British officials it became clear that the Director-General, René Maheu, had been impressed by Hobsbawm at a meeting and had invited him on his ‘personal authority’. This led to the ODM lodging ‘strong personal remonstrance’ to Maheu on the basis that the invitation to Hobsbawm was in ‘direct conflict’ with previous agreements 1, and that it was ‘liable to cause considerable damage to UNESCO’s reputation in the UK’. There were other warnings that such actions could be seen ‘as evidence of undue communist influence’ in UNESCO.

In December 1969 it was decided that an official would need to go to Paris to discuss the matter – interestingly, earlier in the deliberations a ‘nice coach trip’ to Oxford to discuss Berlin’s invitation was dismissed as unnecessary – but Maheu had the flu. As it became clear that a number of the original invitees would be unavailable to attend in Finland – Berlin was due to be in the USA during April – a meeting between Maheu and an ODM official was arranged for New Year’s Eve.

UNESCO respond in December 1969 – FCO 61/750

By this point it had emerged that Hobsbawm had declined the invitation, but the government still wished to express displeasure about what had occurred. Maheu remained unclear as to what the problem was. ‘When I said that he is a member of the British Communist party,’ reported the official, ‘M Maheu replied “So what?”. They had not approached him as a member of the Communist party, but as a distinguished and well qualified individual.’ The official also wrote, ‘without using the word “apology” or “sorry” the Director General came as close as he is constitutionally capable of doing to apologising for the invitation to Professor Hobsbawm.’

So, what can we learn from this? This is hardly an example of a British version of McCarthyism, but what is striking is that even at a time of détente in Cold War antagonisms there is a great deal of wrangling and anguish about the possible politicisation of representation. Also, there is clearly some resentment between the UK Government – as represented by the FCO and the ODM – and UNESCO (which had apparently been festering for a number of years) and an escalation in concern – see the trip to Paris when one to Oxford was once deemed avoidable. We can also see that Professor Hobsbawm has been defined by his politics in the eyes of many, including the UK Government’s.

Notes:

- 1. In 1966 UNESCO had invited ‘a notorious Communist from Britain’ when they invited Professor John Bernal to a study group on Disarmament and Scientific Research, which led to an apparent agreement that individuals would only be invited to such events after discussion and consent. ↩

It is understable about the stance of the FCO given the time, it was a year after the Soviet tanks rolled onto the streets of Prague and the suggestion of Maurice Dobb (there are two KV files on his time at Cambridge) would not be attractive to HM Government. There may have been public disquiet over paying for an organisation that did good work but also invited Communists at a time when Europe was divided and occupied. Obviously people should be invited after agreement and not for governments to be given a fait accompli. It was certainly not MacCarthyism but HM Government had the right on who represented the country.

Hi David,

Many thanks for your comment.

You are quite correct. Early in the first file – FCO 61/581 – the events in Czechoslovakia and the suppression of the Prague Spring are referenced by the government amongst the reasons countering UNESCO-sponsored Lenin Centenary celebrations.

It certainly is interesting that UNESCO seemingly had an almost antagonistic attitude towards the government – not that I’m suggesting this was deliberate – concerning the academics they approached. More accurately, UNESCO wished to invite those with a strong background to Leninist theory, which they seemed to equate with leftist political leanings, whereas the UK government was adamant that ‘safer bets’ – like Hugh Seton-Watson of SSEES and Alexander Nove of Glasgow – had the appropriate expertise for such an event without such a political slant.

As it was, I wonder who benefited from the failure of any academic to attend.

Simon