Earlier this summer, I worked in the Medieval and Early Modern Team at The National Archives, on an internship funded by the White Rose College of the Arts and Humanities. I’m a PhD student at the University of Sheffield, studying the Archaeology of the Carthusian Houses in Great Britain during the medieval period, but while at The National Archives I learned more about the documents rather than the buildings and objects of this time.

One of the projects I’ve been working on during my internship has been scoping the records in record series C 85: Significations of Excommunication for a potential cataloguing project. There are 9,673 of these fascinating documents, which were used to inform the crown that a member of the public had been excommunicated by the church – the ultimate penalty for disobedience – and had refused to repent for 40 days. The church was asking the crown for help to imprison and punish the excommunicated person.

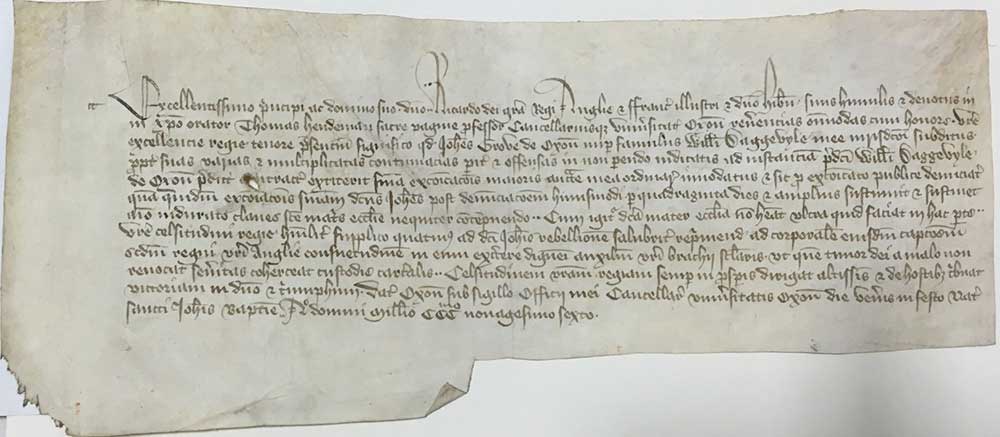

An example of a Signification of Excommunication, dated 22 June 1396, documenting that John Grove has been excommunicated at the instance of William Daggeryle, against whom he committed offences (unknown) and has remained unrepentant for 40 days (catalogue reference: C 85/209/17)

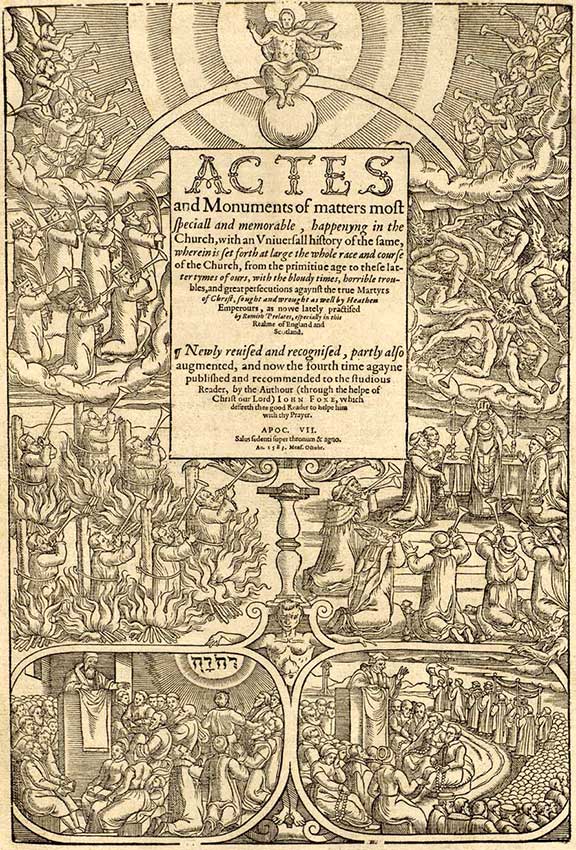

The title page of John Foxe’s Actes and Monuments from the 1583 edition (from The Acts and Monuments Online)

These documents are written in Latin, and range in date from 1220 to 1611, so we see a variety of different reasons for excommunication. These could be failure to pay tithes, adultery, sacrilege or suspicion of heresy. Particularly for the reign of Queen Mary (1553-1558), the majority of records relate to heresy.

What is most interesting about these later records specifically is that often the people named in our documents can be matched up with those in John Foxe’s ‘Acts and Monuments’.

Heresy

One such person was Thomas Tomkins. From the signification (C 85/127/4) we know that he refused to denounce his Protestant views, and was therefore branded a heretic and excommunicated, along with five other men. The document is dated 9 February 1554, and has been signed by Bishop Edmund Bonner.

From Foxe’s ‘Acts and Monuments’, we can discover that Tomkins was a weaver from Shoreditch. Bishop Bonner (also known as ‘Bloody Bonner’) imprisoned him at Fulham Palace for six months for his religious views, where he was beaten regularly.

Eventually, Bonner became so enraged by his obstinacy during questioning that he held Tomkins’ hand over a candle flame until it blistered, in an attempt to induce him to turn to Catholicism. This still did not change Tomkins’ views, and so he was taken to Newgate Prison where he stayed until 16 March 1555, when he was burned at the stake in Smithfield.

Bishop Bonner burns Tomkins’ hand in an attempt to make him change his religious views (from The Acts and Monuments Online)

Another case is that of John Tolye, a poulter of London, who conspired with another to rob a Spaniard. He was found guilty and sentenced to be hanged. When at the gallows in Charing Cross, Tolye denounced Catholicism and the Pope, and called upon the spectators to do the same.

After his death and burial, a counsel of priests decided that for violating the Pope’s holiness, Tolye must be burned to expiate his sins. So, they ordered Tolye’s body to be dug out of his grave, and put on trial. He was asked certain questions about his faith which, being dead, he was unable to answer, and was therefore condemned a heretic. At this time the punishment for heresy was to be burnt at the stake, so on 4 June 1555 Tolye’s body was laid on a fire and burned as a heretic.

![Image of extract of the Signification of Excommunication for John Tolye, which reads '[John] Tolye, lately a citizen and poulter of the City of London, deceased…'](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/01152612/C-85_127_7.jpg)

‘[John] Tolye, lately a citizen and poulter of the City of London, deceased…’ – extract of the Signification of Excommunication for John Tolye, dated 4 May 1555 (catalogue reference: C 85/127/7)

Sacrilege

But the interesting stories do not only lie in accusations of heresy. My favourite story is that of Hugh Knight, a farmer, who defaced an image of the Virgin Mary in the chapel of St John the Baptist in Newport, near Bishop’s Tawton, Devon.

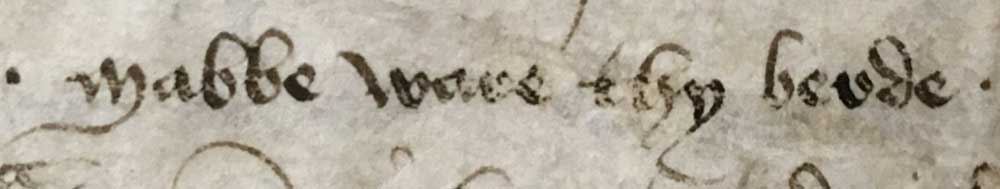

The signification (dated 12 May 1441) describes his actions: he took a tallow candle to the image of the Virgin Mary and blackened the chin and nose with smoke. Having done this he scorned the image, saying ‘Mabbe ware thy berde’ (wear thy beard).

Hugh Knight’s exhortation to the Virgin Mary, having given her a beard made of candle smoke (catalogue reference C 85/79/25)

Exhumation

Another odd case is from the late 14th century, where three men from Leigh in Somerset – William Newbury, John atte More and Adam atte Style – were excommunicated for exhuming the body of Isabella atte Putte. What they intended to do with the body having exhumed it remains a mystery, but they were presumably imprisoned for their actions, and her body returned to the grave.

With only a short amount of time in which to research these documents, I haven’t been able to do as much as I would have liked, but they are so interesting, and there is so much to learn from them about the citizens of England in the Middle Ages. In many cases, the person was excommunicated just for failing to pay tithes, which meant that no one could associate with the excommunicate and they were not allowed to receive the Eucharist or take part in the liturgy, although they were still required to attend Mass. The excommunicate would not be able to offer prayers for the souls for the departed and if they died while excommunicated, they could not be buried in consecrated ground. This was a serious penalty which would have hugely affected the lives of the accused, and their families, especially if they were later imprisoned or punished for their actions.

You can find out more about excommunication and heresy in these books, which are available to view in The National Archives library:

- Donald Logan, F. 1968. ‘Excommunication and the Secular Arm in Medieval England. A Study of Legal Procedure from the Thirteenth to the Sixteenth Century’, Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies

- Duffy, E. 2009. ‘Fires of Faith. Catholic England under Mary Tudor‘, New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press

- Vodola, E. 1986. ‘Excommunication in the Middle Ages‘, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press

The University of Sheffield has also digitised Foxe’s Acts and Monuments which is freely available to view online at: The Unabridged Acts and Monuments Online or TAMO (HRI Online Publications, Sheffield, 2011).

Fascinating blog! I especially like the details about the bearded image

[…] penalty for not paying your tithe was excommunication, and that was big. The U.K. National Archives uncovered a collection of paperwork detailing how, when, and why individuals have been […]