In July 2017, some of the highlights of the Royal Collection’s print room will go on display at the National Portrait Gallery, including original sketches by Leonardo da Vinci and Holbein. Before these rare sketches were sent to be displayed, members from our Medieval and Early Modern Teams were invited to visit the Royal Collection and view the works, including several pieces by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/8-1543).

Sir Henry Guildford 1527, by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/8-1543)

The Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017

Holbein’s portrait sketches – preparatory studies to be converted into painted works – give a fascinating insight into the creative processes which underpinned his work, but they also shed light on those members of the English court who commissioned the works. The majority of these sitters are well known characters who frequently inhabited the court of Henry VIII around the time of Holbein’s two visits to England, 1526-28 and 1532-43.

In this blog we will look at these visits in more detail, and look for traces of Holbein’s activities, networks and movements around the time that these incredible sketches were being produced.

First visit to England

There are several documents at The National Archives which relate to Holbein’s first stay in England and his connections with the humanist movement, a group which included men such as the influential writers Erasmus and Sir Thomas More (whom Holbein sketched in 1526-7). It is clear from our records that Holbein kept himself busy when not engaged in the commission of portraits.

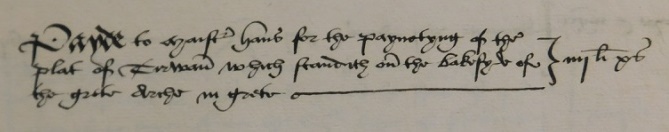

Another member of this influential group was the courtier Henry Guildford, whose portrait Holbein sketched in 1527. From very early on during his first visit to England, Holbein was recorded as working for Guildford, assisting him in his capacity as master of the revels. Guildford’s account book for stores and revels at Greenwich in 1527 (E 36/227), for example, records that ‘maist[er] hans’ earned £4 and 10 shillings for the painting of a ‘plat of Tirwan’ (a panorama of the siege of Thérouanne) that was placed on a ‘grete arche’.

Henry Guildford’s account book for revels at Greenwich (catalogue reference: E 36/227, fol. 11)

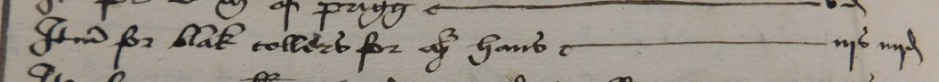

Alongside these payments for Holbein’s work, he also received more practical gifts, including ‘blak collers’ worth 3 shillings and 4 pence (these collars were probably an item of decorative clothing, rather than overalls for painting, as black was an expensive colour in the 16th century.

Henry Guildford’s account book for revels at Greenwich (catalogue reference: E 36/227, fol. 16v)

Holbein’s royal paintings

Holbein returned to England for a second time in 1532, and for the rest of the decade he obtained a prominent position at court, gaining commissions to paint several prominent individuals, including two of Henry VIII’s queens (Anne Boleyn and Jane Seymour), as well as his son Edward, Prince of Wales (later Edward VI).

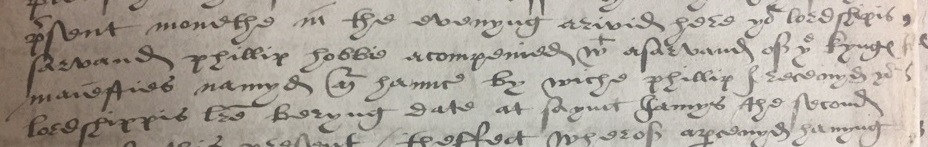

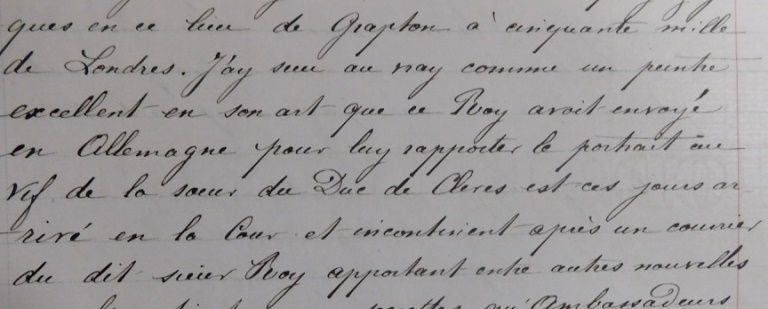

Detailed accounts of Holbein’s commissions at court, and his role as Henry VIII’s court painter can often be found in our collections of State Papers. In 1538, for example, we find reference to a servant of the King’s majesty, ‘namyd Mr Haunce’, in correspondence between the diplomat John Hutton and Thomas Cromwell.

Letter between John Hutton and Thomas Cromwell (catalogue reference: SP 1/130 fol. 47)

Cromwell’s account book gives further insight into Holbein’s presence at court, revealing his wages. A payment made on 4 January 1539 reveals that ‘hanns the paynter’ received 40 shillings by his ‘Lords commandement’, a substantial sum of money. This was an artist who was clearly in demand, and able to charge well for his work!

List of payments for January 1539 in Thomas Cromwell’s account book (catalogue reference: E 36/ 256 fol. 117)

During the 1530s, it was not only in England Holbein was kept busy in service to Henry VIII. In his capacity as a noted painter within the English court, Holbein was the ideal candidate to engage in Henry’s marriage negotiations with Anne of Cleves in 1539.

As PRO 31/3/9 records, the French ambassador to the English court, Charles Marillac, wrote back this year to his king, Francis I, detailing Henry’s negotiations among the other court gossip. Marillac noted that the English king had sent an ‘excellent’ painter to Germany to paint a portrait of Anne. This painter was Holbein, whose portrait convinced Henry to agree to the marriage (although the later disappointment of the king was well noted when Anne didn’t live up to her billing).

Transcript of letter between Marillac and Francis I dated 1539 detailing events surrounding Henry VIII’s marriage negotiations (catalogue reference: PRO 31/3/9)

Trade and commerce

John Godsalve c.1532, by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/8-1543)

The Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017

One image that left a lasting impression on the team was the drawing of the politician John Godsalve (c.1505-1556), who in 1532 earned a position at the Office for the Common Meter of Cloth of Gold and Silver. It was in this very place, the Steelyard of London, where Godsalve would have been in contact with the Hanseatic merchants who were Holbein’s patrons. During this period Holbein was living and working in the Steelyard so it is very possible they even crossed paths regularly.[ref]1. Dale Hoak, ‘Godsalve, Sir John (b. in or before 1505, d. 1556)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004[/ref]

In contrast to some of Holbein’s initial sketches, which have faded and lost much of their colour due to being framed, Godsalve’s portrait drawing illustrated just how rich and vibrant the colours in these drawings would originally have been. This image – which may possibly have been intended as a finished work – has the additional materials of both pen and ink, adding vibrancy and depth to the drawing. This depth was complemented by the use of pre-prepared, pale pink paper, which mirrored the natural skin tone of the sitter and added further colour to the portrait.

These two important players in the English court may have come together in political or cultural circles, but they may also have engaged together with trade and social connections. In May 1538, Holbein was granted a licence and grant by the king to purchase 600 tonnes of beer (presumably for the purposes of trade rather than for consumption!).

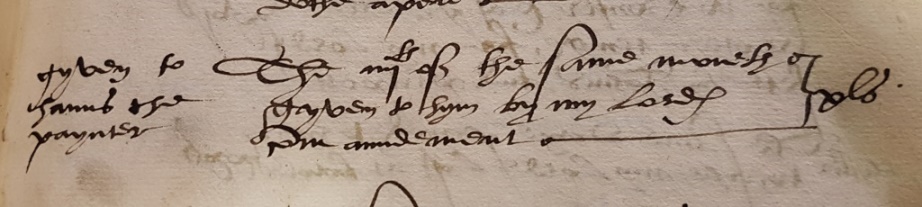

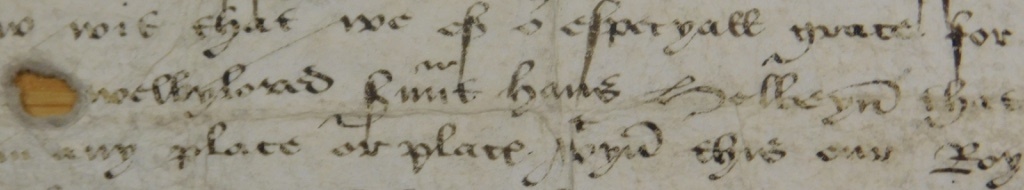

License for beer for Hans Holbein in May 1538 (catalogue reference: C 82/740)

In these entries, Holbein was described as ‘well beloved’, pointing towards the fact that by this point he was well known, and had made a name for himself. Nevertheless, this document also provides a different context for Holbein and his other day-to-day activities. Holbein was clearly a man of many interests!

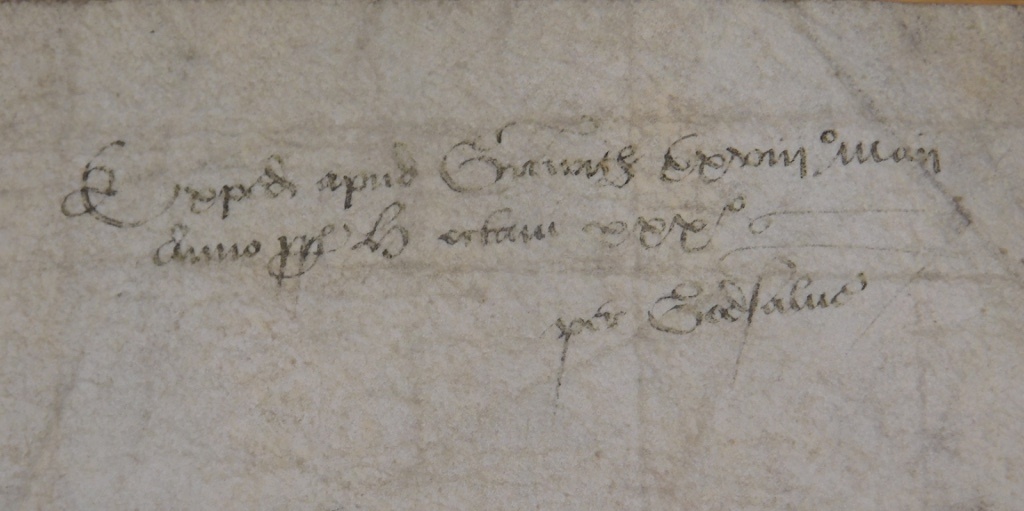

While the licences themselves were from the king, they also provide evidence of a link between Holbein and Godsalve. On the back of the grant, we find evidence that this process had been expedited at Greenwich by Godsalve himself, lobbying the king on Holbein’s behalf.

Expedited at Greenwich on 28 May, the 30th regnal year of Henry VIII’s reign, by Godsalve (catalogue reference: C 82/740)

Insight into art

The visits of Hans Holbein the Younger to England put him right at the heart of the new humanist movement sweeping the court of Henry VIII. His skills and dexterity as a sketcher and painter ingratiated the German with leading figures of this group, who commissioned him to produce exquisite portraits, sketching and painting the great and the good of English society.

As our documents show, these relationships were not limited to that of the painter and sitter, but extended to professional (and possibly social) relationships, as Holbein made connections throughout the court. The relationships give us a new insight into the works of art which hang in the National Portrait Gallery, and take us back to the man behind the paintings.

For more on Holbein, have a look at what the National Portrait Gallery have in store for their exhibition on ‘The Encounter: Drawings from Leonardo to Rembrandt’.