‘Enemy Of The Stars’ on display at The National Archives.

‘A Graphic War‘ is an exciting display of sculptures by artist Ian Kirkpatrick, which explore the aesthetic and cultural significance of graphic design of the First World War.

Kirkpatrick’s works draw upon familiar imagery and subject matter from the front line as well as the home front, with a particular emphasis on the experience of war in Leeds. The pieces are all inspired by artefacts, which were explored during his Leverhulme Trust funded residency with Leeds Museums and Galleries.

The whole concept of bringing the seven pieces of artwork from the ‘A Graphic War’ collection to The National Archives all started when we visited ‘The First World War: Commemoration and Memory’ conference at Imperial War Museums North. Here, we saw the impressive figure of ‘Blast’, which had been installed at the conference by Ian Kirkpatrick, and Lucy Moore, curator at Leeds Museum and Galleries.

With such strong links to Leeds, and with the First World War 100 programme well underway, we began to wonder if it would be possible to bring the local to the national. Could these works be displayed in our unique space and be tied to our collections through the artist’s interpretation? Could the messages portrayed around disability, the roles of women in war, and Leeds manufacturing and its losses during the war still be relevant when the sculptures were displayed at The National Archives?

Ceramic gunner from the collections of Leeds Museums and Galleries.

‘Blast’ is based on a ceramic machine gunner held in the Leeds City Museum collection. Machine guns were one of the main killers during the war and accounted for many thousands of deaths.

The 15th Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment (Leeds Pals) landed in France in March 1916, joining the British build up for the Battle of the Somme.

On 1 July 1916, the first day of the Somme, the Leeds Pals battalion was shelled in its trenches before Zero Hour and, when it advanced, was met by heavy machine gun fire. The battalion’s casualties totalled 24 officers and 504 other ranks; of which 15 officers and 233 other ranks were killed.

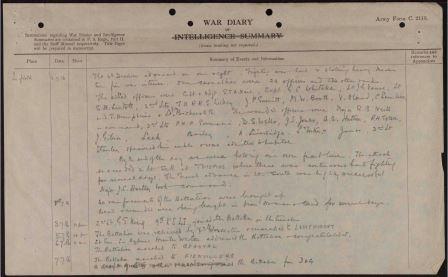

War diary of the 15th Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment (catalogue reference: WO 95/2361/3)

One of the officers listed in the war diary as being killed on 1 July was 2nd Lieutenant Major William Booth, a Yorkshire and England cricketer. Lieutenant Booth’s service record (WO 339/36598) records his death and gives us a snapshot in to the life of one of the men lost on that day.

The record details that he was buried in no man’s land near West Yorks Memorial, Hebuterne. However, when you search for him on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website, you discover that he now has a grave stone in Serre Road Cemetery No.1 (the village of Serre is located 11 kilometres north-east of Albert). In the spring of 1917, the battlefields of the Somme and Ancre were cleared by V Corps and a number of new cemeteries were made, three of which are now named from the Serre Road. It would make sense that this is how Lieutenant Booth ended up in this cemetery.

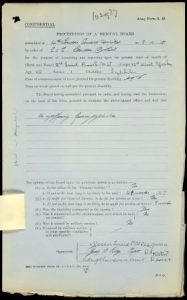

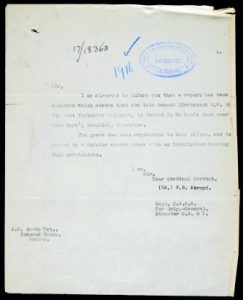

- Service record of 2nd Lieutenant Major William Booth (catalogue reference: WO 339/36598)

- Service record of 2nd Lieutenant Major William Booth (catalogue reference: WO 339/36598)

There was a different story awaiting many of those who survived the war. Nearly six million British and German men were disabled by injury or disease between 1914 and 1918. Shrapnel from exploding shells – and bullets from machine gun fire – destroyed the flesh of these men fighting and left behind some of the worst injuries ever seen. Many returned home with paralysis due to damaged nerves; others came back missing one or more limbs.

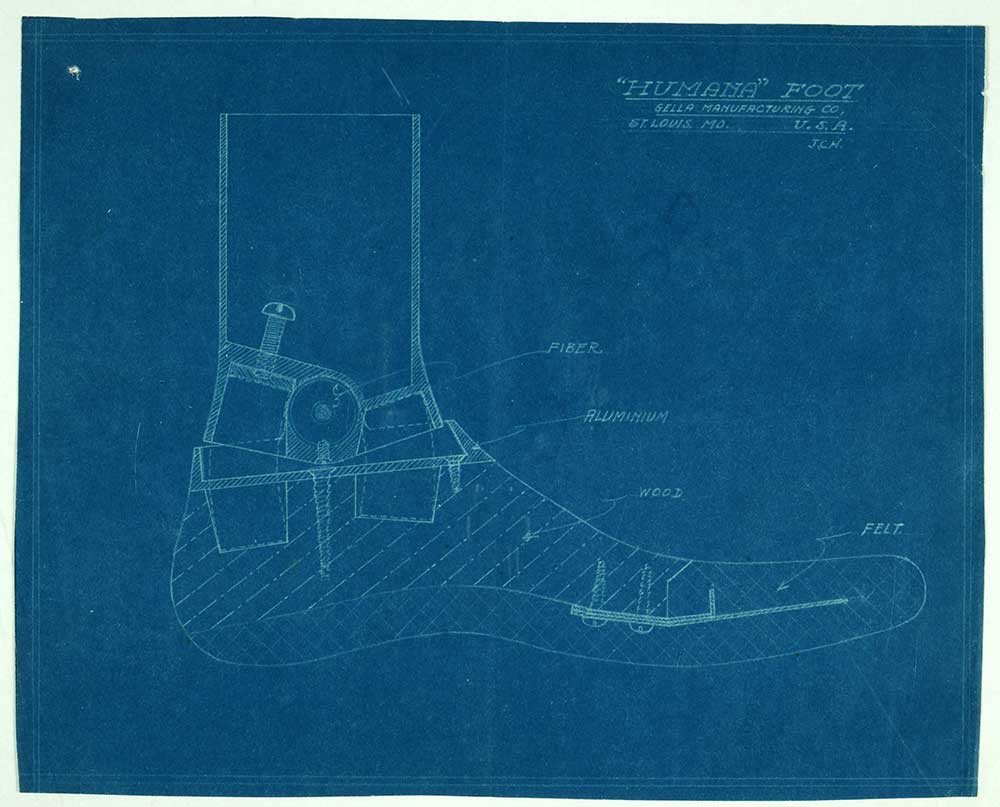

Plan for an artificial foot (catalogue reference: MUN7/285)

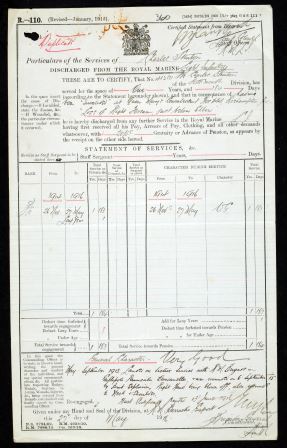

Attestation papers of Charles Stinton (catalogue reference: ADM 157/2690/1)

One such man was Charles Stinton, who served in the Royal Marines. He enlisted in York on 26 November 1914, and served in the Portsmouth Division. One aspect which makes Stinton so relevant to this project is that he was born in Leeds and, after discharge, decided to return to Leeds. Not even a year into his service, in September 1915, Stinton received wounds to his neck and shoulder and his right hand was blown off in a bomb explosion. Like many men who returned with a missing limb, he was treated at the Queen Mary Convalescent Auxiliary Hospital in Roehampton, London – one of the pioneering limb-fitting hospitals in Britain at this time.

Injury through warfare can be seen throughout Ian’s sculptures, most prominently in ‘Kingdom Of Dreams’, as shown below. Here, the rider slumps forward, as if in pain. The positioning of his bayonet, although to his side, mimics a fatal blow and his face is hauntingly pale.

‘Kingdom of Dreams’ by Ian Kirkpatrick

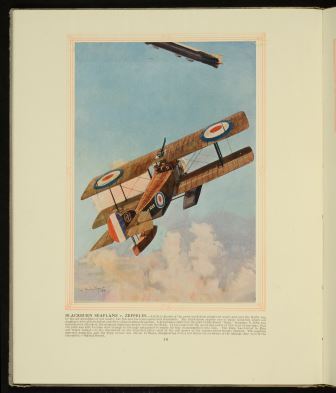

Blackburn plane attacking a zeppelin (catalogue reference: AIR 1/2306/215/18)

Leeds was a centre of industry during the war. The Blackburn aeroplane and motor car company’s main works were based in the city and throughout the war years the company developed a number of essential devices of warfare, including torpedo planes for the RAF.

There were however accidents – a prototype called the ‘White Falcon’ piloted by Rowland Ding crashed at Roundhay Park, Leeds 1917. Zeppelins and planes were part of the inspiration for ‘Enemy of the Stars’, which is suspended ‘mid explosion’ in our main hall. Kirkpatrick here juxtaposes the powerful image of a bird (or falcon) in flight with the wreckage of an imagined, aeronautic hybrid. This contrast renders a vulnerability on a seemingly inanimate object.

Still linking to the theme of industry, Kirkpatrick also reflects on the female workforce during the war, with female imagery featuring prominently in his sculptures.

During the First World War, large numbers of women were recruited into roles which had been vacated by those men who had gone to the Front.

One such place which was involved in this was the Leeds National Filling Factory. In the summer of 1915, the site for this factory was chosen as Barnbow – situated between the railway stations of Cross Gates and Garforth. Groups of workmen, employed by the North East Railway Company, constructed a railway siding laying a main track way into the factory complex. By the end of 1915, work had begun at the factory.

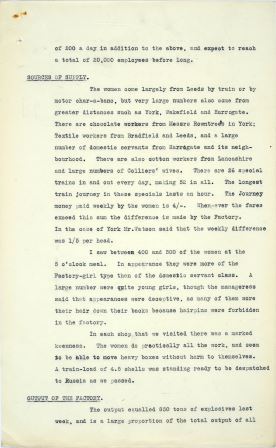

At The National Archives, we have a report from a visit of Mr. G.H. Duckworth to the factory, from September 1916. By this stage, there were 13,000 women employed, as well as 1000 men and boys. Women were being engaged in this work at the rate of 200 per day. The regular wage was 6d. per hour for women, for a 48 hour week – a wage which was unheard of before the war. The factory ran day and night, seven days a week. These women undertook various tasks, from the filling of shells to the screwing (by machinery) of fuses to the noses of large shells.

Leeds National Filling Factory (catalogue reference: MUN 5/153/1122/2/1)

Leeds National Filling Factory – Report of a visit by Mr G.H. Duckworth (catalogue reference: MUN 5/153/1122/3/7)

Work undertaken here was of a dangerous nature. Duckworth refers to one area as the ‘danger building’ and states that no extra wage was given to those who were employed there. Instead, a red overall was worn in there, in place of the usual khaki, as a badge of honour of sorts. This so-called danger building was the Amatol factory. Here, women were working with dangerous chemicals. Amatol is a compound constructed of TNT and ammonium nitrate. In the cartridge areas, women were constantly working with cordite – which when you work with for a prolonged period of time, can turn the skin yellow. Other unpleasant outcomes ranged from trapped fingers to Amatol poisoning – which could be fatal.

Duckworth explains that the doctor for the site hoped that his prophylactic treatment (washing and powdering the hands and the face) would prevent future deaths from Amatol poisoning. It is also interesting to note that he mentions half wages being paid immediately if the girl is told to absent herself from the factory, until she is well again. Three months after this report was written, an explosion occurred in one of the blocks (on 5 December) killing 35 women and injuring many others.

Kirkpatrick’s ‘Britannia’ clearly portrays this work done by women, with particular relevance to the work done at Barnbow. The female figure is holding a shell high, and her stomach is packaged with what could be cartridge shells. This also ties in with the women’s rights movements taking place at the time – with the symbolism of the sometimes militant Suffragettes and the idea that female workforces during the war played their part in gaining votes for women.

‘Britannia’ by Ian Kirkpatrick

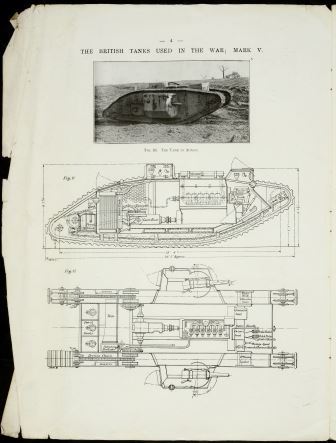

The design for ‘Britannia’ is also based on the MkV tank, a version of the landship deployed in 1918 during the closing stages of the war.

Pamphlet: British Tanks by Sir Eustace H T D’Eyncourt (catalogue reference: MUN 5/211/1940/34)

Indeed, the First World War significantly drove developments in design and technology. From 1914 both sides began developing landships and aeroplanes for military use. The first fifty Mk1 tanks were in action on the Somme from mid-September 1916, and even though many broke down, or got stuck in the mud, they were deemed a success.

On 17 September 1916 Sir Douglas Haig was quoted as saying, ‘we have had the greatest victory since the battle of the Marne. We have taken more prisoners and more territory, with comparatively few casualties. This is due to the tanks. Wherever the tanks advance we took our objectives and where they did not advance, we failed to take our objectives.’

Hopefully, this blog has given you insight into some of the exciting ways in which ‘A Graphic War’ ties in with our own collection and research interests here at The National Archives.

The exhibition runs from 3 October 2016 to 31 March 2017 at The National Archives.