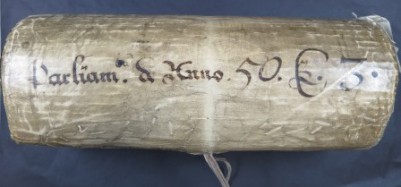

Parliament Roll of the Good Parliament (catalogue reference: C 65/30)

Today marks the 640th anniversary of opening of the Good Parliament of spring 1376. The session is one of the most important in constitutional history: it witnessed the first election of a speaker of the commons and the first use of impeachment in parliament to remove several government ministers, including the chamberlain William lord Latimer.

By the time it finally dispersed on 10 July, it was the longest parliament in English history up until that time.

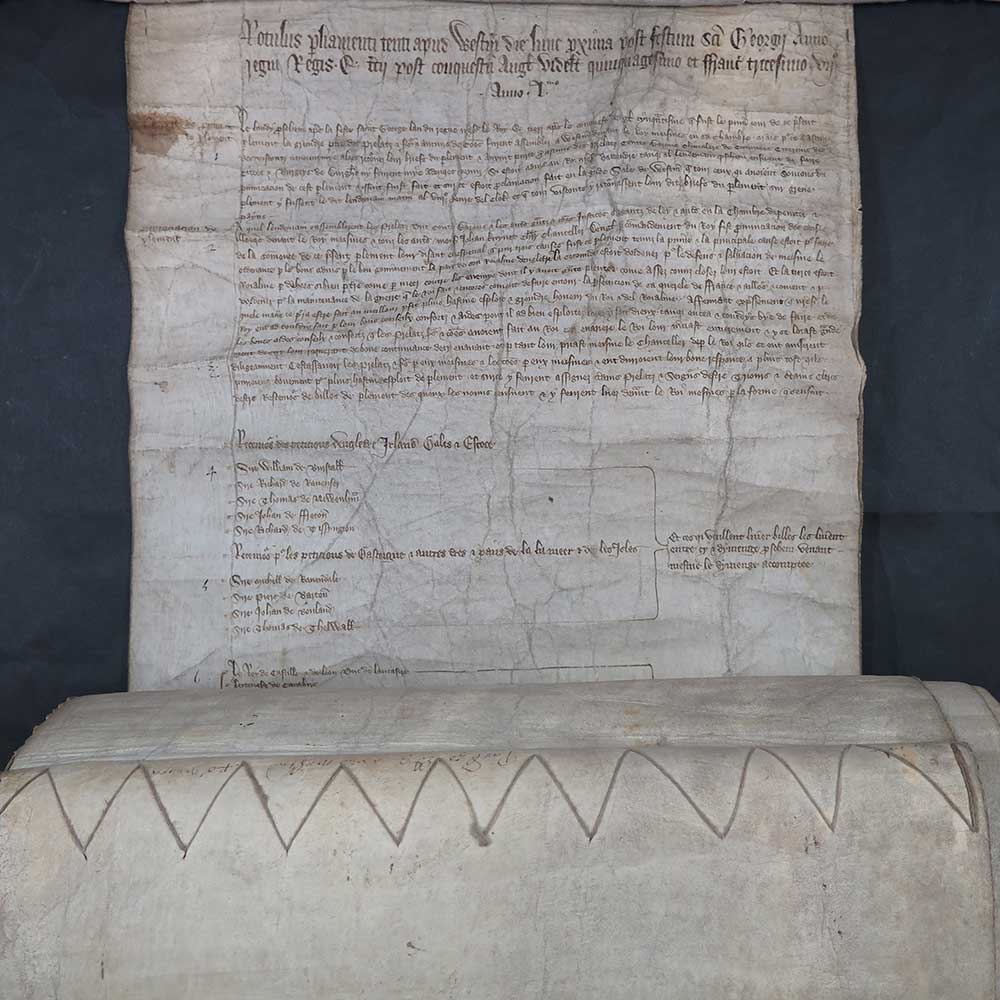

The parliament started in usual fashion. On Tuesday 29 April, after an adjournment of one day for latecomers, the chancellor, Sir Thomas Knyvet, addressed the assembled lords and commons before the king in the Painted Chamber of the Palace of Westminster. After presenting the reasons why parliament had been called, he requested a grant of taxation and the continuation of the wool customs for one or two years. Particular emphasis was placed on the need of funds for the defence of the realm against England’s many enemies and for the maintenance of the war with France.

Opening of the Good Parliament on the roll of parliament (catalogue reference: C 65/30, m.1.)

Chapter House of Westminster Abbey (image source: wikicommons)

After this, however, any sense of normality quickly disappeared. The commons entered into a debate lasting several days during which they took to the floor, one by one, to express their dismay at the state of the realm. One knight stated that it seemed unreasonable to him that the commons be taxed, because the king would not require such funds if the money previously levied had not been woefully misspent and mismanaged by the king’s avaricious councillors.

His comments were a reflection of the fractious political atmosphere in the build up to the Good Parliament. The health of King Edward III had deteriorated and it was widely perceived that he was being controlled by a group of corrupt group of royal favourites. Of particular contention was his relationship with his mistress, Alice Perrers, a low-born woman who rose to enormous wealth and power following the death of the queen, Philippa of Hainault, in 1369.

According to the ‘Anonimalle Chronicle’, after each man had spoken his piece Sir Peter de la Mare, the steward of the earl of March, summed the grievances and arguments of fellows in such an ‘effective wise and convincing fashion’ that he was marked out as a leader among his peers, and they decided to elect him as speaker.

On 9 May the commons returned to the Palace of Westminster, where de la Mare informed the lords that they had found many faults ‘which will be to the profit of the king and kingdom to put right’ and that they would make no grant of taxation until they had been addressed.

When asked to specify in greater detail de la Mare presented four primary charges:

- That the Staple had been removed from Calais.

- That Latimer and the London merchant courtier Richard Lyons had made loans to the crown at unreasonably high rates of interest.

- That both men had bought up royal debts at heavily discounted prices.

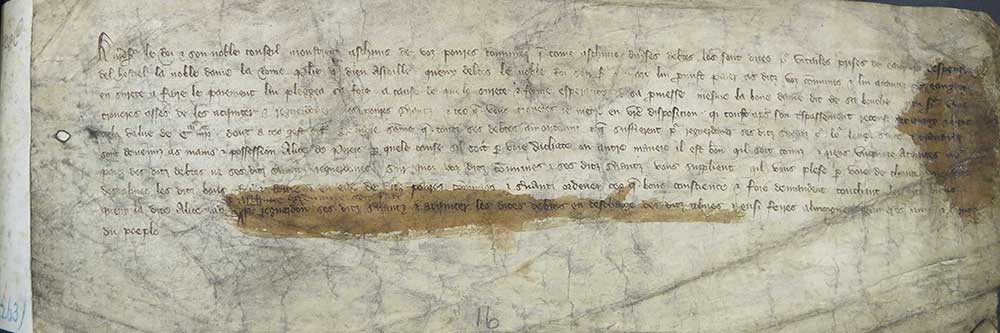

- That Alice Perrers, had ‘two or three thousand pounds of gold and silver’ a year from the king’s coffers, and it would be therefore of great profit to the realm to ‘take measures to remedy her [Alice’s] outrageous behaviour, and, as much for the king’s honour as his personal good, to have her removed from his presence, for she had tarnished his honour both in this land and all the neighbouring kingdoms.’

Faced with growing pressure the crown, led by the king’s son John of Gaunt, capitulated to the commons demands. Alice, Latimer and John lord Neville, the steward of the household, were removed and a new royal council installed. Latimer, Lyons, and Neville were impeached, along with several merchant financiers. Lyons was sentenced to forfeit all his lands and goods and was imprisoned at the king’s pleasure. Latimer was also imprisoned and fined 20,000 marks (£13,666).

Alice Perrers, meanwhile, was made to promise ‘that she would not in future presume to go to the king’ and placed under an ordinance which ordered her to stop using her influence inappropriately ‘on penalty of whatever the said Alice can forfeit and of being banished from the realm’.

Petition submitted against Edward III’s mistress Alice Perrers for non-payment of debt (catalogue reference: SC 8/104/5166)

These proceedings were interrupted by the death of Edward III’s son and heir, Edward the Black Prince, on 8 June. On the 25 June the Black Prince’s son, the future Richard II, was bought into parliament so they could see and honour the heir presumptive. The commons requested that he be made Prince of Wales, before being sharply reminded that such titles were bestowed by the king, not parliament.

The achievements of the Good Parliament did not last long. In October, both Latimer and Alice received full pardons (although she would be tried and convicted after Edward III’s death) and the council which had been imposed on the king was dismissed. When parliament met again in January 1377 the convictions of all those impeached were formally overturned. Retribution was also enacted. In November Peter de la Mare was incarcerated in Nottingham Castle and the bishop of Winchester, who had opened supported Latimer’s trial, was deprived of his temporalities.

In the long term, however, the Good Parliament would prove to be hugely significant, paving the way for the Peasants’ Revolt in 1381, the deposition of Richard II in 1399, and ultimately the English Civil Wars and the Commonwealth during the 17th century. The power exerted by the commons challenging the wishes of the government, aristocratic counsellors and even the king, set the precedent for standing up to the crown in this way.

The accountability of ministers, officials, and special advisors, remains a cornerstone of modern government; the misappropriation of funds allocated to one thing but spent elsewhere is questioned; poor or unacceptable performance in office is challenged and addressed. Heads might not always literally roll like that of the chancellor Simon Sudbury in 1381 or William de la Pole in 1450, but plenty of officials continue to be sacked or punished on the basis of grievances raised in parliament.

Has time changed?, 2016 minus 1376 makes it the 640th not the 660th anniversary!.

Hi David,

Thanks for your comment. I’ve corrected the blog.

Best,

Nell