One hundred and ninety years ago, in April 1828, French explorer René Caillé became the first European to reach Timbuktu, in present-day Mali, and return alive. He was awarded 10,000 francs by the Société de Géographie, the French geographical society, and the book he published was funded by the French government. Caillé, however, had been preceded in Timbuktu by an Englishman, Major Alexander Gordon Laing.

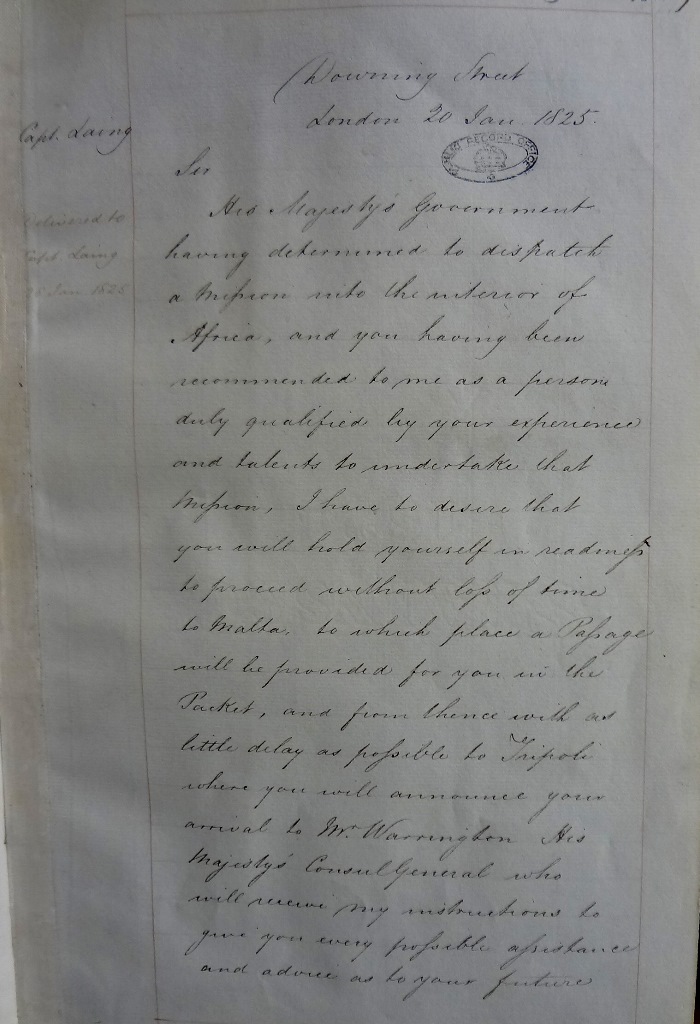

In January 1825, Laing was instructed by Lord Bathurst, the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, to ‘proceed from Tripoli to Timbuctoo’ to gather information on the Niger basin and determine the exact location of this city (CO 392/3).

Timbuktu’s legend was based on the accounts of Arab travellers who had visited the city before the 16th century. Its name alone conjured up wondrous images of wealth and mystery. The roofs, they said, were made of gold… These stories prompted a race to Timbuktu between two old rivals: Britain and France. In the words of the British consul at Tripoli, Hanmer Warrington, ‘the French were making efforts to pluck from England’s brow those laurels to which the latter was so justly entitled’ – so time was of the essence (FO 76/19).

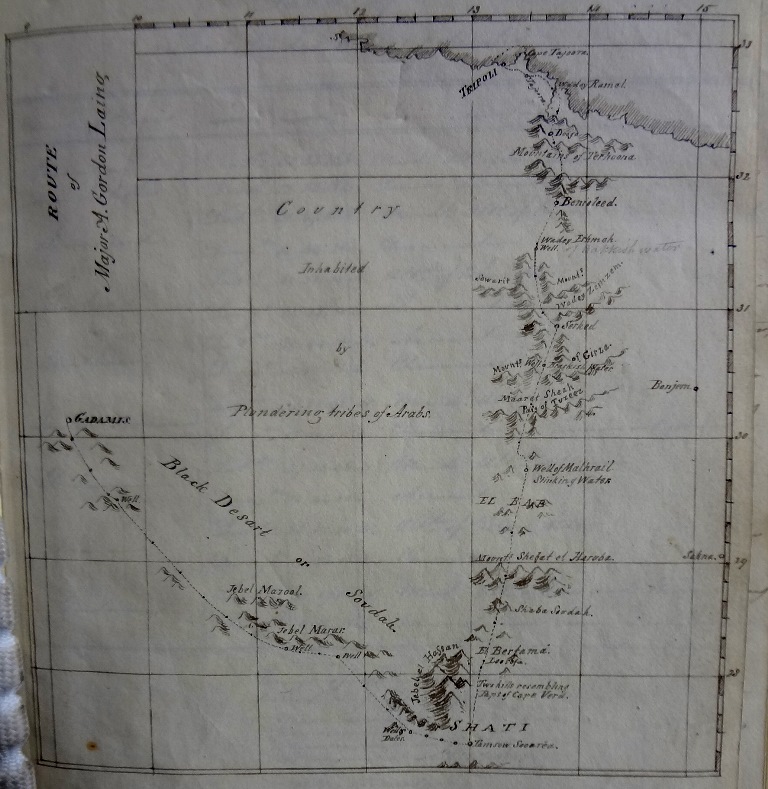

Laing left Britain in February 1825, and reached Tripoli on 9 May. Warrington was quite taken with him, although he feared that ‘the delicate state of his health’ would prevent him from completing the mission. Laing seemed to get better in Tripoli, however, and started planning. It was agreed that the expedition would go through Ghadames, in what is now North-western Libya. The road from Tripoli to Ghadames was virtually unexplored and travelling along it would provide Laing with an opportunity to fill in a blank space on the map.

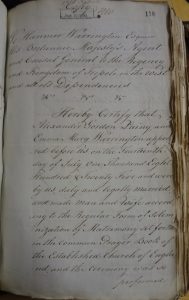

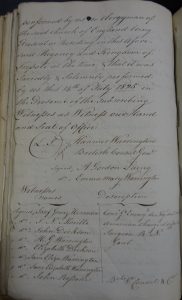

On 14 July 1825, rather unexpectedly and after a whirlwind romance, Laing married Emma, Warrington’s second daughter. The consul wasn’t pleased. Sure enough, he found Laing ‘clever and gentlemanly’, and thought ‘his talents were conspicuous’ but, given the circumstances, he tried to block the wedding. He wrote to lord Bathurst:

After a voluminous correspondence, I found my wishes (…) and displeasure quite futile and of no avail, and under all circumstances, both for the public good, as their as their mutual happiness, I was obliged to consent to perform the ceremony, under the most sacred and solemn obligation that they are not to cohabit till the marriage is duly performed by a clergyman of the established Church of England (FO 76/19).

In other words, the marriage was not to be consummated. Warrington put it quite clearly: ‘I will take good care my daughter remains as pure and chaste as snow.’

- Laing’s marriage certificate, 14 July 1825 (catalogue reference: FO 76/19)

- Laing’s marriage certificate, 14 July 1825 (catalogue reference: FO 76/19)

A few days after his wedding, Laing set out for Timbuktu under the guidance of Sheikh Babany, a merchant who had lived in Timbuktu and promised he could take Laing there in two and a half months. Having travelled across the Sahara, he reached Ghadames on 13 September, after what he described as ‘a very tedious journey’. The journey had indeed been difficult: Laing had lost his barometers – which couldn’t sustain the heat nor the constant ‘camel shaking’ – he was down to his last two thermometers, his chronometer had stopped due to the variations of temperature, and the glass of his artificial horizon had become dim because of the friction of sand. He wrote to Warrington: ‘And a camel having unfortunately placed his great grouty foot upon my rifle one night as I lay with it on the ground, snapt the stock in two’ (FO 76/19).

In Ghadames, Laing did a bit of digging and found out, much to his surprise, that the walls he had described as ‘a mere mockery of defence’ dated back to Roman times; he was looking for coins, and would probably have settled for an inscribed tablet or two, but instead uncovered only broken sarcophagi (CO 2/15).

Pressing on, Laing reached Salah, in present-day Algeria, in December. In January 1826, Laing and his party left Salah and started marching across the Tanezrouft desert. This was when things really started going wrong.

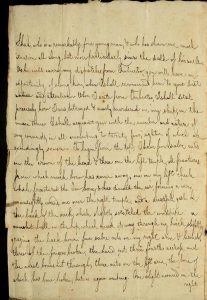

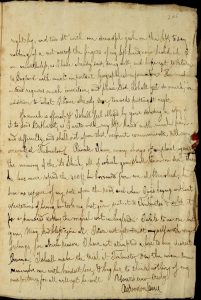

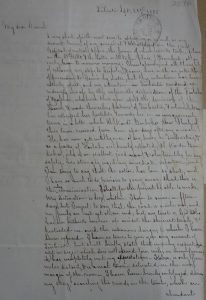

Writing to Warrington on 10 May 1826, Laing described very vividly the injuries he received during a Tuareg attack. He didn’t describe the attack itself, but from the number of wounds he sustained, and the severity of them, it must have been rather savage. Writing with his left hand, as his right hand had been ‘cut three fourths across’, he explained that he had received 24 wounds, ‘eighteen of which are exceedingly severe’. He had numerous sabre cuts all over the head, face, arms and legs, multiple open fractures, and a musket ball in his hip had ‘made its way through [his] back, slightly grazing the back bone’. He was left for dead.

Against all odds, he somehow managed to survive both the attack and the 400-mile journey to Sheikh Sidi Muhammad’s territory, from where he was writing. ‘I am nevertheless, as I have already said, doing well’, he assured the Consul – with either great courage, foolish bravado, or a bit of both (CO 2/20).

- Laing to Warrington, 10 May 1826 (catalogue reference: CO 2/20)

- Laing to Warrington, 10 May 1826 (catalogue reference: CO 2/20)

- Laing to Warrington, 10 May 1826 (catalogue reference: CO 2/20)

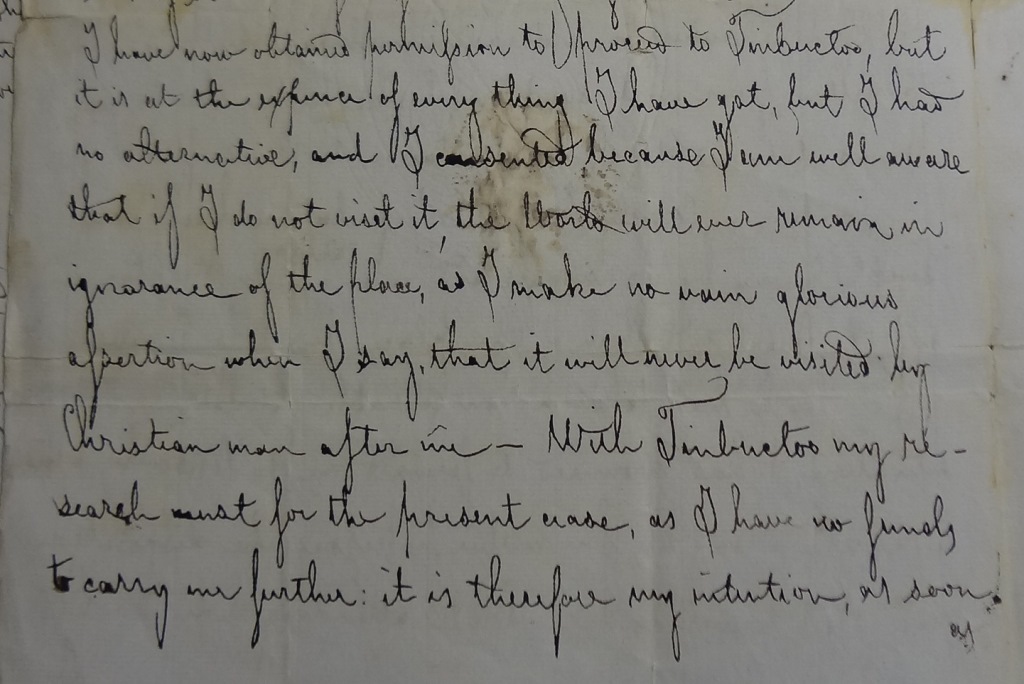

Laing certainly didn’t lack self-confidence. In December 1825, writing from Salah, he had declared; ‘I shall do more than has ever been done before, and shall show myself, a man of enterprise and genius.’ In July 1826, recovering from his gruesome wounds and still writing with his left hand (which somehow makes his handwriting easier to decipher), he told Warrington:

I am well aware that if I do not visit [Timbuktu], the world will ever remain in ignorance of the place, as I make no vain glorious assertion when I say that it will never be visited by Christian man after me (CO 2/20).

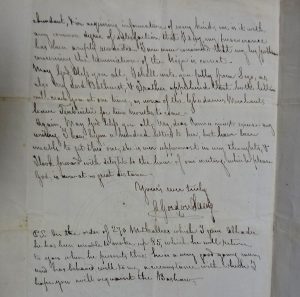

Laing finally reached Timbuktu on 13 August 1826. Writing to Warrington on 21 September, he said that he was anxious to leave, and hoped he could do so early in the morning of 22 August. Instead of trying to retrace his steps back to Tripoli, he said, he would proceed to Sego (present-day Ségou, in south-central Mali) – even though he knew ‘the road [was] a vile one’.

It’s difficult to know what Laing found in Timbuktu, as he didn’t have time to give much information about the city. He said that the place had ‘completely met [his] expectations’, but that his position was rather unsafe due to the unfriendly disposition of the locals. One tantalising sentence in the letter reveals that he kept busy ‘searching the records in the town, which are abundant’ (CO 2/20). It can safely be assumed that he was talking about the famous Timbuktu manuscripts, many of which were destroyed in 2012-2013.

- Laing to Warrington, 21 September 1826 (catalogue reference: CO 2/20)

- Laing to Warrington, 21 September 1826 (catalogue reference: CO 2/20)

This was the last Warrington was to hear from his son-in-law. Laing left Timbuktu as planned, but a couple of days later he was ambushed in Sahab, about 30 miles north – this time, he didn’t survive. His servant Bongola, who survived the attack and made his way to Tripoli, described the attack in January 1829: ‘I awoke with a blow from a sword on the head which made me giddy and my head fell. When I recovered, I saw (…) my master’s head off.’ (FO 76/26)

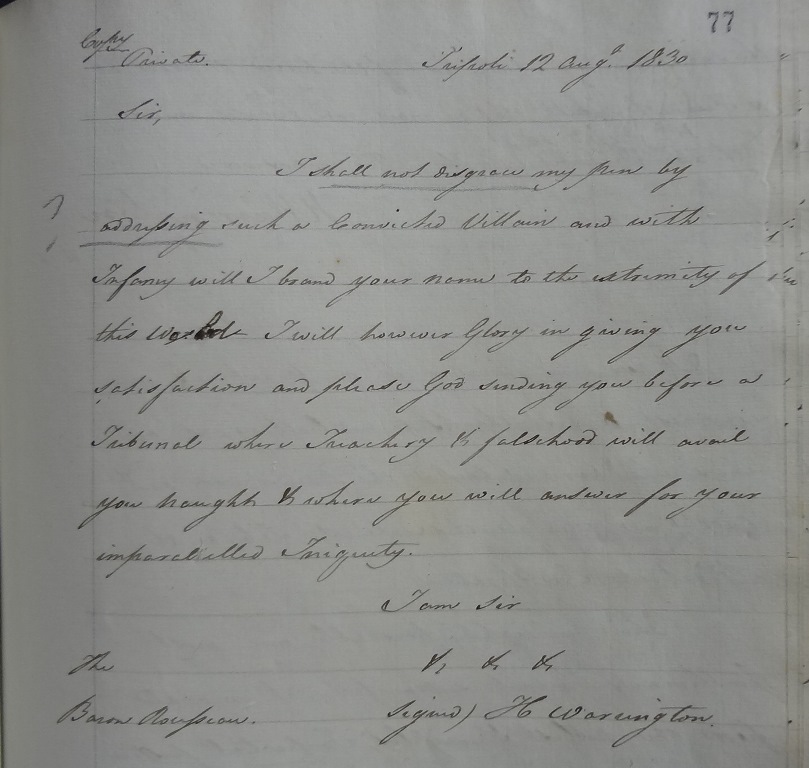

Laing’s head was left under a tree, and all his papers, journals and maps disappeared. These missing papers led to an Anglo-French crisis. Warrington had fought against France in Spain and clearly hated the French. He convinced himself that the French Consul at Tripoli, Baron Rousseau, had conspired with a local sheikh to get his hands on the papers (FO 76/26). When René Caillé published the account of his journey to Timbuktu, Warrington accused him of having based his book on Laing’s papers (FO 174/33).

By February 1830, Warrington was convinced that Rousseau had played a part in Laing’s murder, and accused the Pasha of Tripoli of having helped him. The two consuls exchanged insulting letters for a while, Warrington writing to Rousseau on 12 August 1830:

Sir, I shall not disgrace my pen by addressing such a convicted villain and with infamy will I brand your name to the extremity of this world… (CO 2/20)

However, the French were not as bad as Warrington thought. In 1932, the French authorities at Timbuktu unveiled a bronze plaque in his memory. Laing –a typical 19th Century explorer, plucky and competitive – might have found comfort in the fact that Caillé was extremely disappointed when he arrived in Timbuktu, only noticing the ruins and a general atmosphere of declined grandeur. We will never know what Laing really thought of the fabled city, but reading his letters and journals we can once more conjure up the old legend of Timbuktu – beauty, wealth, and remoteness.

- Major Laing’s house at Timbuktu (catalogue reference: CO 1069/17)

- The plaque unveiled in 1932 by the French authorities (catalogue reference: CO 1069/17)

Laing was a Scotsman, born in Edinburgh, not an Englishman, as stated in the first paragraph.

[…] interesting read, this post describes the race to be the first European to reach the fabled city of […]

Interesting. Could you digitize and publish the FO 76/19 and other FO 76 files on the Discovery website?

We would love to explore Warrington’s letters and correspondence by ourselves, not just read this single blog post.

Hello. Thanks for getting in touch.

You can order paper or digital copies of our records: find details on our website at nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/record-copying/

Best regards,

Liz.